Pura vida!

In Costa Rica, that national expression has many interpretations, including “Enjoy life,” “Take it easy,” and even “Hello” and “Goodbye.” Yet the literal English translation ("pure life") and touristic understandings of the phrase are lacking in comparison to its use by ticos — the Spanish word Costa Ricans use to describe themselves.

Some ticos say “pura vida” refers to a way of living — recognizing that life is good and that whatever your current situation, it can always be worse for others.

Such is the case for one of that nation’s most formidable icons: the jaguar.

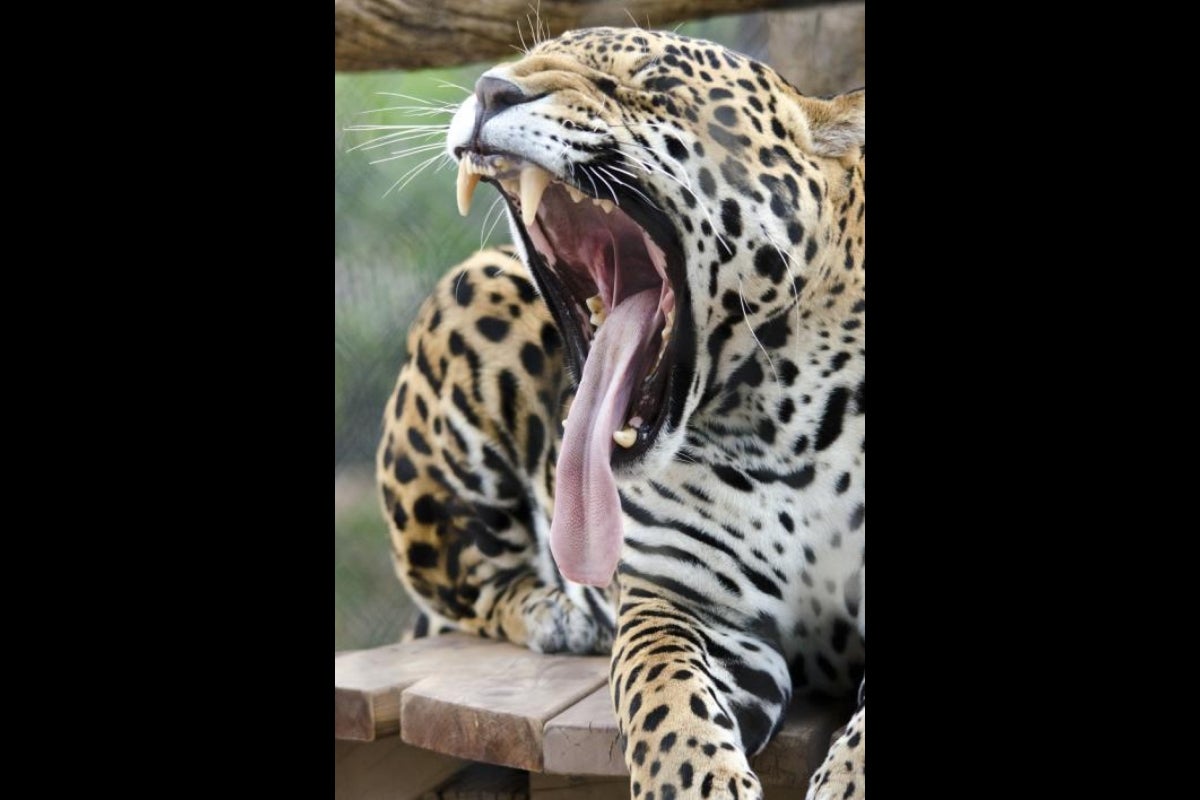

As the largest of the big cats in South America, the jaguar (Panthera onca) is a stealthy predatorThis powerful carnivore dominates its habitat, feeding on anything from deer and tapirs, to fish and turtles. It can ambush its prey from the treetops, crushing an animal’s head with its tremendous jaws. , nimble on land and in the water. Male jaguars mark huge swaths of land, each claiming as much as 50 square miles as his territory. They are solitary animals, other than during mating and pregnancy seasons when the male will live with the femaleA stunning animal with tawny fur covered in black rosettes, the male can weigh up to 250 pounds. A female jaguar gives birth to two to four cubs at a time. She teaches them to hunt after they are 6 months old. By age 2, the cubs are out living on their own. . These beautiful beasts can live 12 to 15 years in the wild.

However, the jaguar is in serious danger. It appears on the IUCN Red List as “near threatened,” and human activities, including poaching and deforestation, are the leading causes of its decline. Current research may indeed show that the species could qualify for a higher threat category.

“A jaguar needs a huge area to survive,” said Jan Schipper, a conservation research post-doctoral fellow working in partnership with Arizona State University’s School of Life Sciences and the Phoenix Zoo-Arizona Center for Nature Conservation. “There’s not enough habitat left, so we have to figure out how to use the area that’s available in a creative way.

“In addition, poaching has been a huge problem for a long time, partly because there’s not only jaguars, but also puma moving in and eating goats and sheep. A lack of sufficient natural habitat pushes these mammals closer to human populations,” he added.

Schipper’s interest in jaguar research began 12 years ago with collaborators from ProCAT, a non-profit, non-governmental organization focused on sustainable conservation strategies; CATIE, a Costa Rican center for tropical agricultural research; and the University of Idaho. The National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) joined their research efforts more recently. Schipper and other conservation biologists are studying whether it’s feasible to create a wildlife corridor in Costa Rica that would allow jaguars the room they need to thrive.

“We’re trying to understand how the mammals are distributed and what variables are important to explain how they use this space,” said José Fernando Gonzalez-Maya, a member of ProCAT and the scientific director of Sierra to Sea Institute in Costa Rica, a non-governmental organization working to improve biodiversity and human well-being. “We want to understand how human influence, in terms of hunting and in terms of all the modifications they do to the habitats, how they affect animals using this space.”

Human impact

In Costa Rica, as in many countries, it’s easy to see the negative impact Homo sapiens have on animals and their habitats.

In addition to the creation of towns, cities and freeways, humans use land for agriculture, cattle ranching and coffee plantations, among other things. In addition, hundreds of thousands of acres of tropical rain forests are clear-cut to make room for African oil palm plantations, which provide fruit used to create palm oil — an edible vegetable oil. Used in everything from crackers and candles to cosmetics and biofuels, palm oil has become one of the largest agricultural industries in Costa Rica.

The deforestation created by this industry, along with the creation of banana, pineapple and in some cases coffee plantations, has pushed jaguars out of their habitats and into increased conflict with humans. Poaching, whether for trophy hunting or to keep the big cats from killing cattle and sheep, is a serious problem.

“I think the problems we have here really epitomize the problems that we have across the range of the jaguar,” said Schipper. “Shrinking area. Lack of enforcement in national parks. There’s a lot of parks in Costa Rica, but unfortunately, some of them are very remote and don’t get the same level of support that they need to actually protect the parks from poachers going in, which is an incredibly challenging problem.”

Creating wildlife corridors

Schipper and Gonzalez-Maya are part of a larger ongoing effort in the Latin American country to preserve what remains of the critical tropical habitat and also protect the species that live there. Many animals living in the Costa Rican rain forest need a cohesive environment to survive and thrive, but with habitats becoming smaller and more and more fragmented, it’s critical for the researchers to find new solutions that can be implemented in the near future.

“One of the key aspects of our study is to actually design and understand how a biological corridor works, and how we can connect the higher parts of this country to the lower parts in the lowlands, connecting protected areas and allowing animals to move throughout the landscape and providing them with all the ecosystem services they need to survive,” said Gonzalez-Maya.

To help understand how the animals are moving within the area, the researchers use camera traps mounted in strategic locations to gather data. But to set up the cameras, the scientists needed to develop new relationships with partner organizations, specifically those with an interest in conservation.

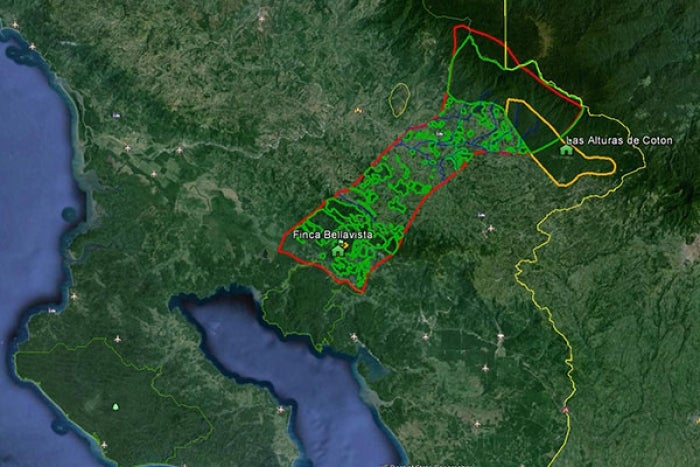

The researchers knew of a 600-acre parcel of land located within the Amistosa corridor. The parcel, previously slated to be clear-cut, was purchased more than a decade ago by new owners who had different plans for the property. Schipper and Gonzalez-Maya eventually partnered with Finca Bellavista, a sustainable tree house community situated between the two sites the researchers are trying to connect. Their hope is that jaguar and other species can use the land to move between the national parks.

“We are proposing to connect La Amistad in the Talamancan Highlands with Corcovado National Park on the Osa peninsula, two large national parks which have jaguar populations,” said Schipper. “La Amistad has a relatively large jaguar population, which we’ve been studying for more than 10 years. The Osa has a very small population mostly due to hunting, poaching and loss of habitat.”

Finca Bellavista is a non-traditional residential community that features sustainable tree houses used for year-round living and tourism, as well as an infrastructure with trails, bridges and zip lines rather than roads and fences.

“This will never be a pristine piece of rainforest, but it doesn’t mean that it can’t be a thriving and healthy home for a lot of the animals that thrive in secondary growth rainforest,” said Erica Elise Andrews, co-owner of the development. “We want our property to be a centerpiece, something we can show off to the rest of the world as a working model of living sustainably within a migration corridor, and within critical habitat that also provides opportunities for research and connectivity.”

Schipper’s research team has access to the land and its resources — critical to gathering their data.

“I think we are uniquely collaborative. This is a multifaceted problem that needs more than interdisciplinary efforts,” said Schipper. “We’re working with biodiversity, economic incentives and agriculture, and we’re trying to piece it all together in this biological corridor. Finca Bellavista is a key component in the landscape, and we’re hoping the animals will move along this trajectory.”

Studying the jaguar

Jaguar, puma, ocelot, tapirs, howler monkeys, sloths, reptiles and a host of other animals thrive in Costa Rica’s jungles. They are well-suited for life in this dense, tropical landscape. But studying these animals is often difficult.

Schipper and Gonzalez-Maya, along with other researchers, have placed hundreds of camera traps throughout several strategic corridor locations. The motion- and heat-activated cameras take hundreds of thousands of animal images, along with some disturbing images of poachers and smugglers. (See a variety of camera-trap images below.)

Setting up the cameras in places likely to capture useful images is no small feat. First, the scientists must find suitable locations and then travel to them, often on foot and carrying large, heavy packs of gear. Research days are filled with planning, hiking, driving, climbing and camping. Multiple crews must coordinate efforts so they don’t duplicate camera coverage. Later, the teams return to each site to gather memory cards or retrieve cameras.

“I’m assisting in setting up the camera traps,” said Chelsey Tellez, a School of Life Sciences graduate and research assistant on the project. “I’ll set the date and time and input the GPS coordinates. We generally look for trails that are game trails, or trails that animals may take. We try to find a tree sturdy enough to hold the camera and then set it up to capture as many animal images as we can.”

Hiking through dense foliage makes it difficult to cover long distances. At Finca Bellavista, the crew uses existing zip lines to reach the top of the canopy.

“In addition to jaguar conservation, we are also looking at how species move across roads and other features in the corridor,” said Schipper. “We’re looking at whether cables are an effective way for animals to get from one side of the road to the other. Arboreal mammals, specifically primates, kinkajous, small carnivores and other animals that live in the canopy, have a hard time crossing the roads and surviving. Creating a cable system may be helpful in connecting habitats.”

Co-owner Matt Hogan said they have seen many animal species return to their land by allowing the forest to be a forest and by keeping the poachers at bay.

“It’s really exciting to see the animals, especially the nocturnal ones that are moving around all night when we are sleeping. Sometimes we hear them and sometimes we don’t. By camera, we’ve captured everything from pumas and ocelots to sloths and kinkajous — all kinds of different critters,” he said.

Private jaguar conservation

The research team also joined forces with a private jaguar conservation effort centered at Las Alturas del Bosque Verde — a sprawling, 32,000-acre ranch in the southwestern part of the country. Here, armed guards who live on the property work around the clock protecting a large population of jaguar from poachers.

“This situation is fairly unique. We’re talking about doing conservation on private land outside a protected area like a national park, so this becomes a different challenge,” Schipper said. “This farm is the upper anchor to the proposed corridor. The Osa peninsula and Corcovado National Park create the lower anchor. These two points are where we are synthesizing this corridor.”

Several hundred residents also live on the property in a tiny village, much like they did 50 or 60 years ago. Schipper and Gonzalez-Maya often reach out to the community, teaching schoolchildren about the animals that live in their backyard.

“It’s really complex because you need to consider all the interests people have in using the landscape for obviously, economic and social reasons. But then, you have the cultural aspect of conservation, which is how people approach the nature, how people use nature, and how people benefit from nature. At the end, conservation only works when you involve people and help them understand that they need the ecosystems to survive,” said Gonzalez-Maya.

Ultimately, both humans and the jaguar need the rain forests to survive. But the jaguar’s fate may also depend on whether a culture and the mind-set of younger generations can be changed to reflect the importance of conserving the big cats and the forests.

“Reaching the children is an important impact we can have,” Schipper said. “We hope the kids go home and tell their parents what they’ve learned, and maybe, if their dad is a poacher or hunter, the kids can apply a little pressure. Maybe over time, changing the mentality people have will reach a newer generation that will not want to hunt jaguar. Maybe they can give up some of the habits of the older generation in terms of illegal poaching, hunting and cutting down the forest.”

Update: Schipper’s research team has completed a draft of its proposed wildlife corridor in Costa Rica. Now, the team is refining the borders, deciding whom to work with and what conservation strategies to employ.

Jan Schipper is a Conservation Research Postdoctoral Fellow in a partnership between ASU School of Life Sciences and Phoenix Zoo-Arizona Center for Nature Conservation. The Mikelberg Family Foundation, Las Alturas del Bosque Verde, ProCAT, Phoenix Zoo and Arizona State University helped make this research project possible.

See the original jaguar story and other stories on conservation at ASU, see the award-winning SOLS magazine. Top photo by Phoenix Zoo

More Science and technology

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to award as much as $100 million to Arizona State University and Deca…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to treatment. In fact, most deaths from cancer are caused by the…

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even change how our genes work, how the instructions coded into our DNA are…