Art and public policy.

They might not sound like they go together, but Kade L. Twist is proof to the contrary.

The ASU School of Art alumnusMFA in Intermedia, 2012. The School of Art is part of the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts. works today as both a multidisciplinary artist and a public-affairs consultant.

“[Art and public policy] feed into each other,” said Twist (pictured above). “It’s really about connecting narratives of indigenous self-determination with the public sphere.”

He didn’t start out thinking that way. Growing up in Bakersfield, California, Twist figured he’d be a plumber, like his dad. “But I wasn’t good enough,” he said. “I’m the failed plumber of the family."

When he was about 18, he started writing. He went to community college in California for a year and a half (where, he jokes, he majored in surfing) and eventually ended up at the University of Oklahoma. He majored in economic development and public policy, within American Indian studies. Twist, a registered member of the Cherokee nation, started focusing on gaining “a better understanding of who we are as subjugated peoples.”

“No one is telling our story,” Twist said. “And the people that are telling our story are typically white educated males, using some kind of liberal narrative structure to reimagine what they think should be done.”

The path of the artist

Deciding that publishing was “too inefficient,” Twist switched from writing to art, because he said there’s more freedom and the medium is more immediate.

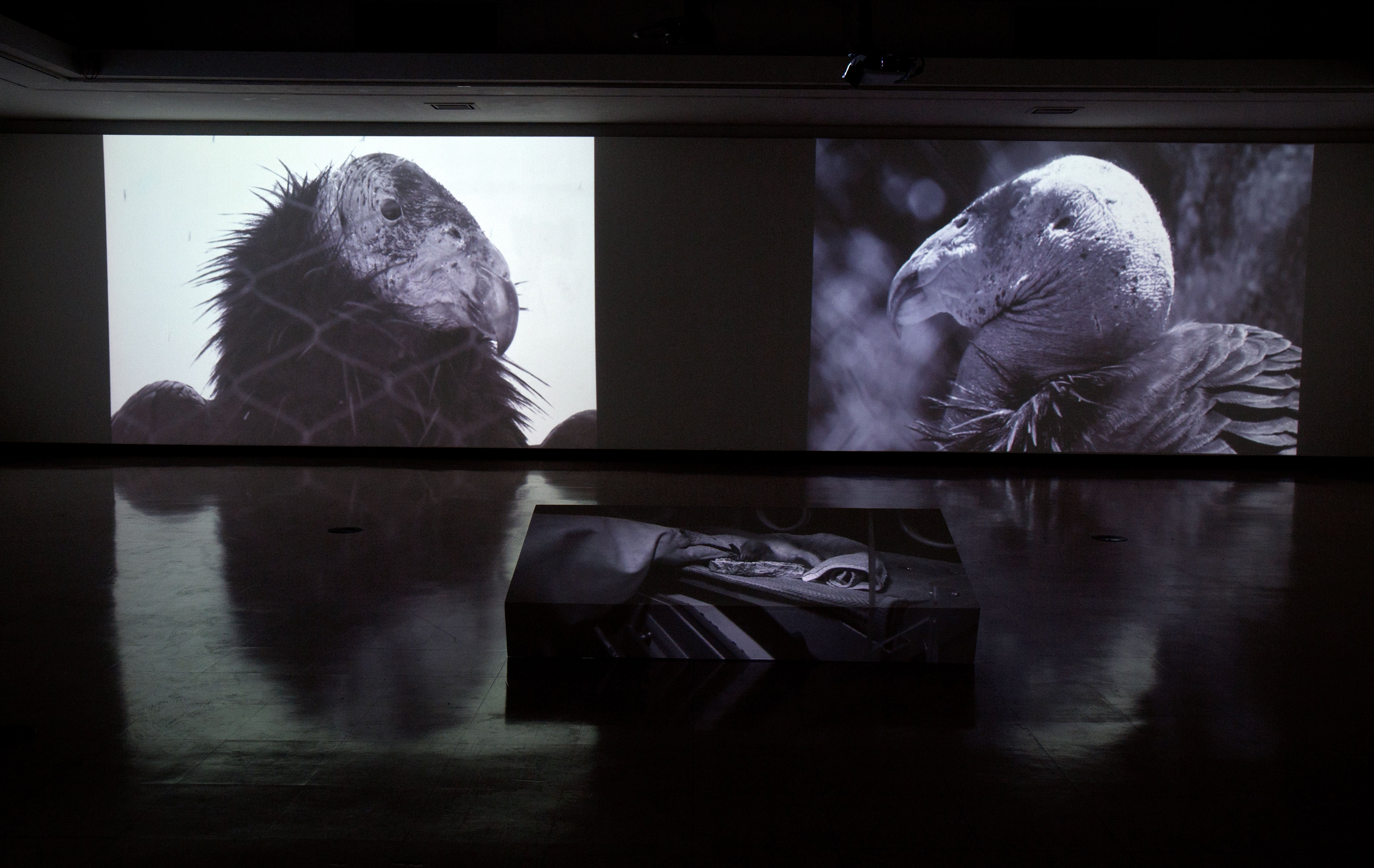

"It’s Easy to Live With Promises If You Believe They Are Only Ideas" by Kade Twist (2012), a seven-channel video installation with sound. Photo courtesy Kade Twist

The most important experience of his development as an artist so far, he said, was being included in a 2006 group show at the ASU Art Museum titled “New American City: Artists Look Forward.”

Curated by Heather Sealy Lineberry and John Spiak, “New American City” invited 23 artists from around Maricopa County to create “a platform for conversations about the possibilities and opportunities for the integration of art in the development of Phoenix.”

“That show helped me grow up,” Twist said. “It created a community of artists within a community of artists.We helped each other, we worked together, lent each other gear. The ‘New American City’ show brought people together.”

Through the show, Twist met Cristóbal Martínez, who later became a member of Postcommodity, the interdisciplinary indigenous arts collective Twist co-founded with artists Nathan Young and Steven J. YazzieYazzie, a renowned artist whose work is in the ASU Art Museum collection, received his BFA in Intermedia from the School of Art in 2014. Martinez is also an ASU alum; he received a doctorate in rhetoric, composition and linguistics from the ASU College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, in 2015, after completing a master’s in media arts and science in the ASU School of Arts, Media and Engineering, in 2011 and bachelor’s degrees in studio art and painting in the School of Art., in 2002..

In 2009, Postcommodity had its first museum show, “Do You Remember When?” at the ASU Art Museum’s Ceramics Research Center. It would re-create the show three years later at the 18th Biennale of Sydney, in Australia.

The installation involved removing a section of the ASU gallery’s concrete floor as well as incorporating elements of traditional indigenous ceremony into the exhibition. It mixed spiritual and intellectual in a powerful way.

“There’s something about working in installations that makes a lot of sense culturally,” said Twist, pointing out that the spaces are temporary, made for a specific purpose and — if the work is strong — transformative. “… Those are all the aspects of ceremony. Those installation environments become places of reimagined ceremony.”

Eyes in the sky

Last year, with support from the ASU Art Museum, Postcommodity produced “Repellent Fence,” an ambitious and powerful piece of land art that Twist thinks “will become (Postcommodity’s) most iconic work.”

On view for just three days in October, “Repellent Fence” consisted of 26 giant tethered “scare eye” balloons, like those used to frighten away birds, floating 50 feet above the desert in a 2-mile line that intersected the border. The Phoenix New Times called the piece “a bi-national suture, stitching the land and communities back together for a moment in time.”

To prepare, the group spent time in communities along the U.S.-Mexico border. Twist said the experience was eye-opening.

“I think I learned more about what it means to be an indigenous person in this hemisphere in the 21st century working on (‘Repellent Fence’) than on any other work I’ve ever worked on before,” Twist said.

The project started out as “a very simple idea,” Twist recalls: looking at the experience of the Tohono O’odham tribe, whose land is divided by the U.S.–Mexico border, and thinking about what that division means.

"Repellent Fence," a 2015 art installation and community engagement. The 2-mile line of "scare eye" balloons intersected the U.S.-Mexico border near Douglas, Arizona.

Photo by Michael Lundgren/ Courtesy of Postcommodity

But in the course of planning their project, the artists learned that “there’s a lot more to that division than just the border dividing the tribe. There’s more legitimacy if you’re American Indian than if you’re an Indian from Mexico. American Indian people, for whatever reason, see themselves as more indigenous, more authentic.”

The experience revealed an issue that Twist calls “incredibly complex.” They realized that there are powerful dynamics in national identities that supersede tribal identities, even though, they say, many try to claim tribal identities are dominant.

“It made us open a larger conversation,” he said. “We started thinking about the region, the borderlands, the true complexity of what it means to be from this hemisphere, what it means to be American, to be Mexican.”

In the end, Postcommodity collaborated with larger communities of people, not just the tribe as they’d originally planned. “It became about the complexity of the mestizo reality,” Twist said.

Going forward

As the collective has gained experience with their process, Twist said, their mission has shifted.

“Over the last few years, we’ve realized that our mission isn’t just to connect indigenous narratives of self-determination with the public sphere. The emphasis is shifting from indigenous self-determination to self-determination for all people. It’s about the power of a community to realize itself without the federal or state government getting in the way.”

It’s a lofty goal, and they seem to be reaching it: “Repellent Fence” garnered local, national and international press attention. And recently Twist was named a 2015 United States Artists fellow, one of the contemporary art world’s highest honors (which brings with it a $50,000 grant).

“I think I learned more about what it means to be an indigenous person in this hemisphere in the 21st century working on (‘Repellent Fence’) than on any other work I’ve ever worked on before.”

— Kade Twist, 2012 ASU School of Art alum

“Kade L. Twist is an extraordinary artist whose work takes on socially, culturally and intellectually challenging subjects in elegant and moving ways,” said Steven J. Tepper, dean of the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts. “His is precisely the kind of voice that American universities should be supporting and amplifying, so that the stories we tell through our works of art, in our films and on our stages can finally represent all of our country’s diversity, creativity and wisdom.”

Twist is quick to credit ASU with helping him get to where he is today.

“ASU has taken phenomenal risks on my behalf and on Postcommodity’s behalf,” he said. “Both the ASU Art Museum and the school, the institution, have been incredibly generous in supporting me even at times when I didn’t deserve it, when I was angry or frustrated with folks at ASU. They still stood by and were always able to help and willing to help, and that continues today.”

In particular, Twist credits the members of his thesis committee — School of Art faculty Dan Collins, Angela Ellsworth and Muriel Magenta — with teaching him critical lessons. Ellsworth in particular helped him see “why you should respect the field you’re working in even though it’s dominated by rich white people, and why it’s important to be in it especially if you’re not a rich white person.”

The appreciation and admiration go both ways. Collins also had work in “New American City,” which is how the two first met.

“Kade’s work for the exhibition featured an actual prosthetic limb that served as the backdrop for a series of enigmatic projections of text in English and in Cherokee,” Collins recalls. “The work underscored what Kade called the ‘prosthetic’ nature of the urban Indian experience. For me, the work was a revelation.”

Today Twist lives in Santa Fe with his wife, Andrea R. Hanley, an ASU School of Art alumBachelor’s degree in studio art (1989). and the membership and program manager at the Institute of American Indian Arts’ Museum of Contemporary Native Arts.

In addition to making art, Twist works on issues of access to health care for the tribes in the area, particularly oral health care, through the Arizona American Indian Oral Health Initiative. Twist, 44, provides technical assistance on generating policy outcomes and organizing at the tribal level.

Does he have any advice for young artists?

“If you really believe in your art form, you need to give yourself enough time. People in their late 20s drop out left and right; they’re just gone,” he said. “They start teaching or go onto a different career because of the financial instability.

“I think about duration — it really is important to stick with something long enough to have your voice come across.”

More Law, journalism and politics

A new twist on fantasy sports brought on by ASU ties

A new fantasy sports gaming app is taking traditional fantasy sports and mixing them with a strategic, territory-based twist.Maptasy Sports started as a passion project for Arizona State University…

'Politics Beyond the Aisle' series to explore the stories of public officials

In an effort to build a stronger connection between students and political and civic leaders, Arizona State University’s School of Politics and Global Studies hosted the first event of its new series…

ASU committed to advancing free speech

A core pillar of democracy and our concept as a nation has always been freedom — that includes freedom of speech. But what does that really mean?Higher education doesn’t have an agenda to curate a…