Michael Smith begins his new book, “At Home With the Aztecs: An Archaeologist Uncovers Their Daily Life,” by discussing what the Aztecs weren’t: blood-mad maniacs compulsively slicing off heads or miserable faceless slaves dying on vast construction projects.

Those splash-page illustrations in National Geographic of thousands of workers toiling on pyramids? The common view of ancient civilizations, from the Aztecs to the Egyptians, is that non-elites were “slaves toiling under the whip of a cruel overseer to build the pyramids and other monuments demanded by ancient despotic kings,” Smith, professor of anthropology in the School of Human Evolution and Social ChangeThe School of Human Evolution and Social Change is an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. at Arizona State University, writes. “But this is a highly inaccurate picture.”

Ordinary Aztecs were well-to-do. They had nice things: bronze bells and needles, crystal jewelry, musical instruments. Noble households had nice things, too; they just had more of them. And everyone wanted the latest styles from Tenochtitlan.

“It was a little bit surprising to me,” said Smith, director of the ASU Teotihuacan Laboratory in Mexico City. “I began with the sort of typical view that these farmers were downtrodden, and serfs or slaves. Finding evidence of a very prosperous, high quality of life was pretty surprising to me.”

The book explores three stories simultaneously: the title subject; what it’s like working on a dig in Mexico; and his experiences raising two daughters while uncovering ancient towns.

“I thought should try something for a popular audience,” Smith said. An agent and a writing coach told him he needed more stories in the book. “Well, I thought, ‘Working down in Mexico with my kids for 15 years, I have lots of stories,’ ” he said. “I asked my wife. I asked my kids. I learned a lot of things I didn’t know.”

Brush fires, bureaucracy, stray dogs, political turmoil, shotgun-wielding landowners, and chronic pediatric gastrointestinal distress were a few challenges Smith surmounted during his fieldwork, work which brought surprises and not a few pleasures.

“Our scientific pursuit of ethnoarchaeology required that we participate in fiestas in Tetlama and eat handmade tortillas (not to mention mole and other tasty foods). We did this partly to gain insight into Aztec food practices (really!) but mainly to enjoy Mexican food at its best.”

Empire-wide trade meant Aztecs had goods from all over. Smith includes tidbits that give a picture of household life. Salt produced in the Valley of Mexico was packed in distinctive rough pottery jars, somewhat like the Provencal clay crocks herbes de provence come in today. The salt was shipped out and purchased in outlying areas like those excavated by Smith. “As they used up the salt, people broke pieces off the jar (to better get at the remaining salt), and these sherds are abundant in all the middens.)”

Smith’s work doesn’t focus on monumental archaeology, which studies pyramids and palaces, but rather household archaeology, which examines daily life like cooking tortillas, eating dinner and mending clothes.

“Commoner life was simply not recorded” by either Aztecs or Spaniards, leaving Smith to piece together what it was like.

Human sacrifice was not part of Aztec daily life. It was “a state spectacle engineered by nobles and priests.” Ordinary people had as much to do with human sacrifices as they do today planning presidential inaugurations or the Super Bowl.

ASU archaeologist Michael Smith (in his office on the Tempe campus) was told he needed more stories in his new book. "Working down in Mexico with my kids for 15 years, I have lots of stories," he said. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

(To get human sacrifice out of the way entirely, Smith points out the Spanish exaggerated human sacrifice as a way of justifying the conquest. Some modern writers have claimed it didn’t exist at all. It certainly did exist; archaeology has proven “beyond a doubt” it existed, Smith writes. No one knows to what extent it existed, however. “Did they sacrifice 10 victims a year, 100, or a 1,000? We simply cannot say,” he writes.)

Archaeology, as Smith reveals, is an interdisciplinary field. He reveals how he applied sociological studies of post-Great Depression Oklahoma farm families and Nobel-winning economics to measuring the wealth of Aztec households. Architecture and urban design come into play as well.

“Any archaeologist anywhere is going to be interdisciplinary,” Smith said. In Mexico he worked with specialists in bones, plants and pottery. “They just have to be. But it’s only at places like ASU where it’s truly interdisciplinary. It’s a real emphasis on the kind of archaeology we do here.”

He also applied local knowledge. Excavating a village called Cuexcomate in Morelos, he hired dozens of local farmers to help with the digging. One mystery was what had happened to the walls atop the foundation walls they were clearly excavating. There weren’t enough stones around to build all the way up to the roofline. “I actually had students count loose rocks around one set of houses to confirm this — not my most popular order,” he writes.

The mystery of what had happened to the walls was discussed during a lunch break one day. One of the oldest workers said, “Any idiot knows these walls were foundations for adobe bricks!” Many walls in the adjacent modern village of Tetlama were built the same way. “This hypothesis was later confirmed when we found fragments of adobe bricks in the excavations,” Smith writes.

Aztec commoners had fewer freedoms and less control of their government than the ancient Greeks, but much more than their counterparts in ancient Egypt or Babylon. That relative freedom and city-state governments that provided a fair return of services “were key ingredients in the success of the Morelos communities.”

The towns Smith excavated were socially solid. They used what we now call New Urbanist principles of permanence over transience, and of sociability and sustainability.

“Any archaeologist anywhere is going to be interdisciplinary. They just have to be. But it’s only at places like ASU where it’s truly interdisciplinary. It’s a real emphasis on the kind of archaeology we do here.”

— Michael Smith, ASU professor of anthropology

“Perhaps these Aztec communities offer lessons in successful community design,” he writes. “Five hundred years ago, these Aztec communities were doing things that experts recommend for the improvement of communities and neighborhoods today. … These ancient Aztec farmers didn’t need experts to tell them how to improve their communities. They figured this out on their own.”

Smith said his findings reinforce the importance of neighborhoods throughout history. The Aztec form of community organization was the calpolli (also written as calpulli). It was a union built by neighbors from the bottom up to achieve common goals. Today it would be called a grassroots neighborhood association.

“(Neighborhoods) are one of the few things in history all cities have,” Smith said. “(Capolli) was something invented by the Aztecs to make their society work for them. Today neighborhoods are important. They’ve been important in any city that’s ever existed for humankind. That’s one message (of the book).”

The book exemplifies ASU’s approach to scholarship that’s promoted and valued.

“It’s really distinct from the way archaeology is done at other places,” Smith said. “There’s a real emphasis on looking at things from other perspectives, bringing in other disciplines, high-risk research projects. The whole atmosphere here and working on other projects allowed me to rethink these results I got from the excavations. A lot of the story I tell about these households and communities is based on re-thinking the evidence.”

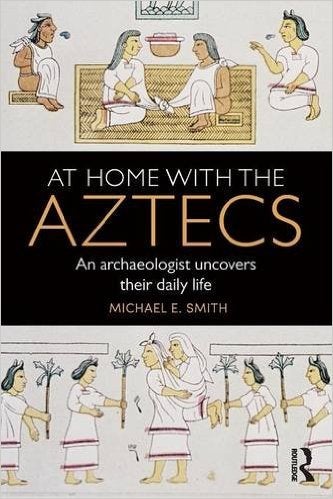

Find Smith's book, “At Home With the Aztecs: An Archaeologist Uncovers Their Daily Life” (Routledge, 2016), here. The book was awarded Popular Book of the Year for 2016 by the Society for American Archaeology.

Top photo by Benjamin Earwicker/Freeimages.com

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU alum's humanities background led to fulfilling job with the governor's office

As a student, Arizona State University alumna Sambo Dul was a triple major in Spanish, political science and economics. After graduating, she leveraged the skills she cultivated in college —…

ASU English professor directs new Native play 'Antíkoni'

Over the last three years, Madeline Sayet toured the United States to tell her story in the autobiographical solo-performance play “Where We Belong.” Now, the clinical associate professor in…

ASU student finds connection to his family's history in dance archives

First-year graduate student Garrett Keeto was visiting the Cross-Cultural Dance Resources Collections at Arizona State University as part of a course project when he discovered something unexpected:…