Humans have been working the land for millennia, cultivating plants or herding animals.

Now researchers from Arizona State University are reporting on a 10-year project that studies the long-term effects humans have had on the land — and the consequences for the communities whose livelihoods depend on the land. Their research has led to some surprising reasons why communities survive or fail.

The Mediterranean Landscape Dynamics Project, led by Michael Barton, a professor ASU’s School of Human Evolution and Social ChangeThe School of Human Evolution and Social Change is an academic unit of ASU's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences., studied human interaction with the land in the Mediterranean region since 2004 to understand how human and natural forces, like climate, began to interact to create socio-ecological landscapes, like the terraced fields, orchards and pastures found throughout the region today.

The focus of the research was on small-holder farmers or herders, who still make up more than 70 percent of the world’s food producers, and how they transform landscapes over long periods of time.

“Our work focuses on how human action, even the kind of farming and herding that is not industrial scale, can have really big effects,” Barton said. “The research helps us to understand the delicate balance between working the land successfully and altering the land to the point where it can no longer support us.”

Among the findings, Barton said, was the idea that there are thresholds that separate success from failure. Farmers and herders can find a balance in working the land that keeps it productive. But as communities grow, they may pass unforeseen thresholds where the land-use practices that once allowed them to thrive begin to destroy the productivity of the land that supports them.

“Go beyond the threshold and everything goes south,” Barton said. “Continuing to do the same things that were successful in grandfather’s day produces increasing problems today.”

Another finding may explain why most people who produce our food either put most of their effort into cultivating crops or into herding animals. Modeling experiments show that while farmers or herders can be successful, those who try to do an equal amount of both eventually fail.

“What happens is when the population starts to grow, the people who are 50/50 expand operations, but then they have dramatic crashes and sometimes never recover,” Barton explained. “It looks like people who are half and half farming and herding are not practicing a sustainable way of life over the long term. It also explains why the world is divided into people who produce our food by mostly farming and who do it mostly by herding.”

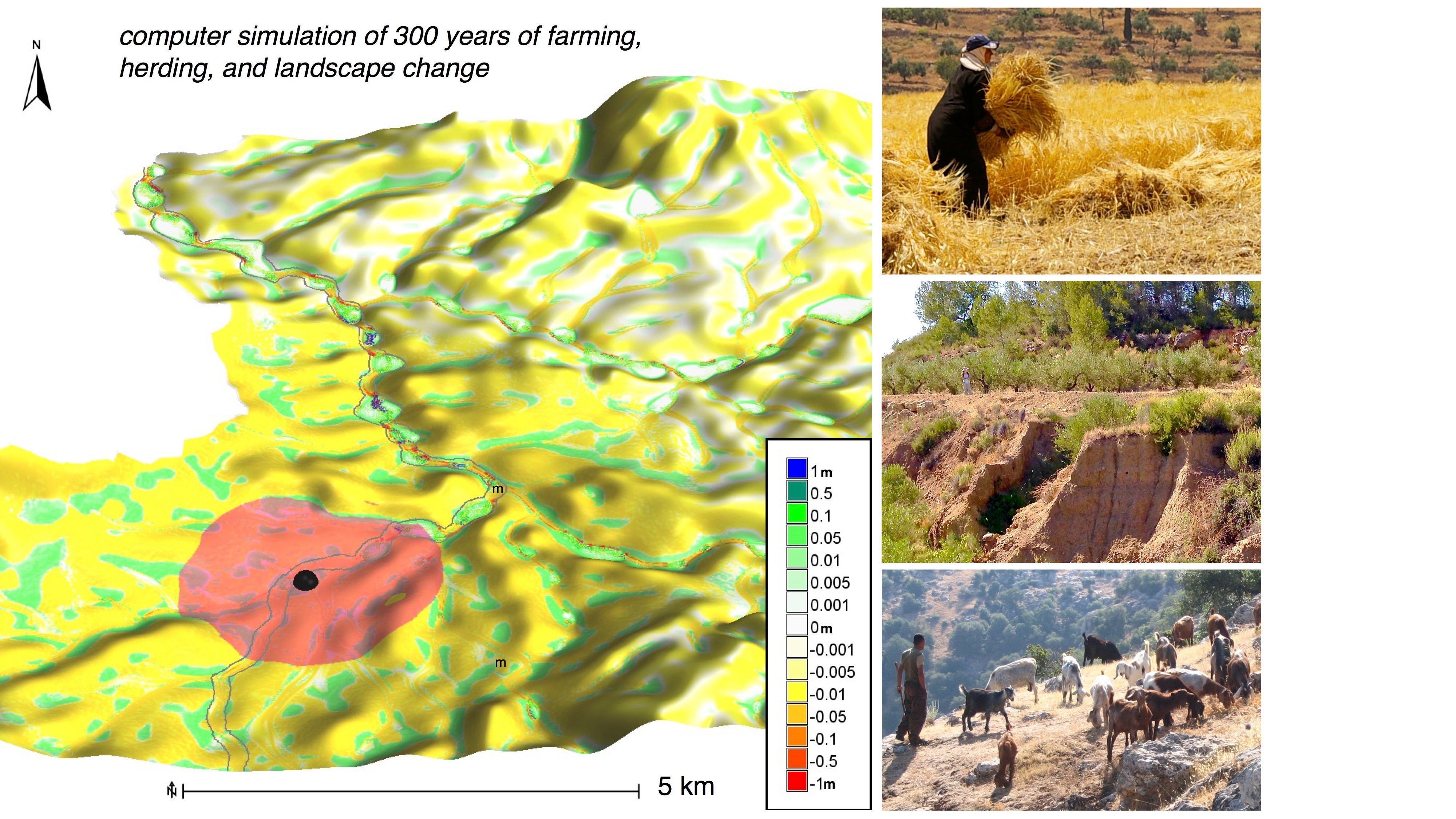

The image on the left is a computer-generated landscape with the colors indicating the meters of soil lost or deposited in different places at the end of a simulation of 300 years of farming and herding. On the right are images of modern Mediterranean landscapes: (from top) wheat farming in Jordan, an olive grove at the edge of an eroded barranco (ravine) in eastern Spain and goat herding in Jordan. Graphic by Michael Barton/ASU and Isaac Ullah/MedLand Project

The research also showed how long-term small-scale farming practices affect large-scale environmental change in the Mediterranean.

“This work has helped us differentiate between environmental changes driven by climate and environmental changes driven by human land use,” Barton said. “We are finding that there may be really strong signatures where the impact of landscape change occurs and they seem to be affected differently by human activity or by climate change.”

Barton and his colleagues, who come from a variety of scientific disciplines and several institutions, combined computer modeling with field research — an approach called experimental socio-ecology.

“Using computational modeling gives us a way to carry out experiments on human environmental interactions over a long period of time,” Barton explained. “More importantly, it can give us insight into the future.”

He explained that the researchers compile data on farming practices, as well as soils, plant cover, climate and other aspects of the environment. They use these to create complex computer models of the impacts of different practices on landscapes. They then tune these models by seeing if they can replicate past human impacts and their consequences. A model that can “predict the past” will be more reliable at showing the potential future consequences of different farming practices in use today.

“We can run a whole series of variations on this to better understand the effects of small-holder farming on the landscape at any time and at any place. We focused on the Mediterranean, but it’s applicable to any semi-arid landscapes,” he said.

This, for Barton, is the future of understanding how humans interact with the land.

“The idea of doing these controlled experiments and contra-factual histories both of the past and of the future is, I think, a really important new way to do socio-ecological science,’” he said.

The findings were presented in the paper, “Experimental socioecology: Integrative science for Anthropocene landscape dynamics,” published in early online issue of Anthropocene. The Mediterranean Landscape Dynamics Project was supported by the National Science Foundation.

More Science and technology

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to award as much as $100 million to Arizona State University and Deca…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to treatment. In fact, most deaths from cancer are caused by the…