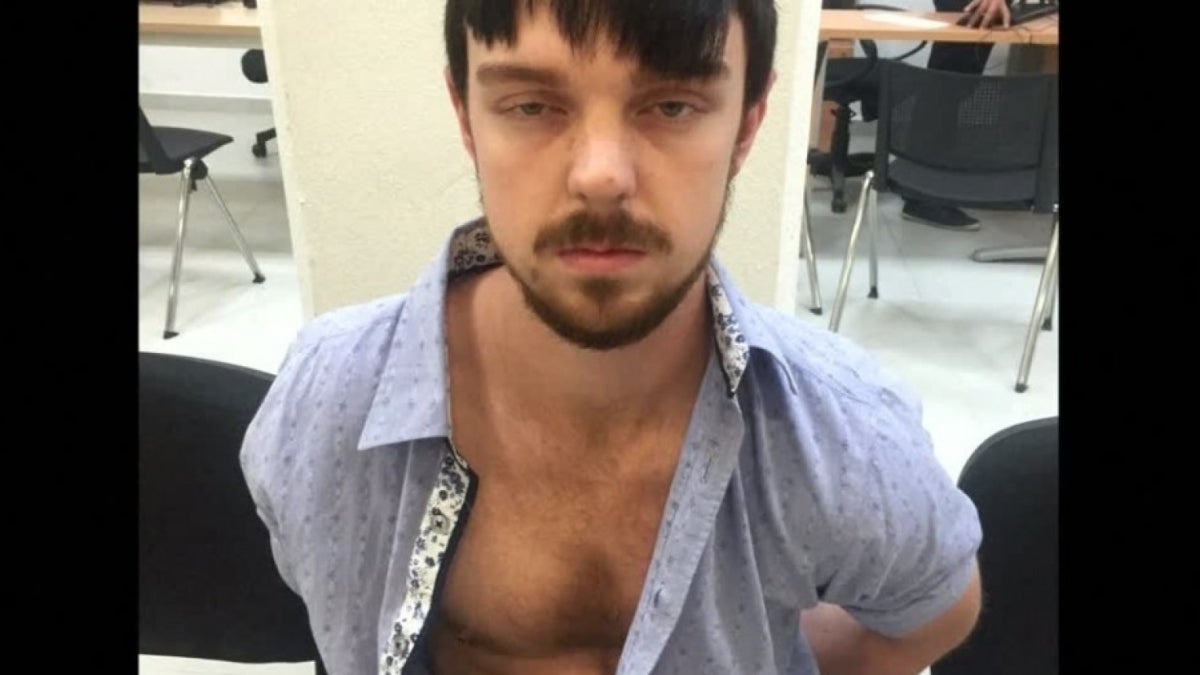

Late Monday night it was announced that Tonya Couch, mother of the infamous “affluenza” teen Ethan CouchPictured above in a photo released by Mexican authorities with dyed-black hair after he has detained in Puerto Vallarta., had posted bail after her bond was lowered from $1 million to $75,000.

This, after the elder Couch was accused of aiding her son in fleeing to Mexico to avoid a probation hearing that might have led to jail time.

It all stemmed from a 2013 incident in which the younger Couch, 16 at the time, killed four people in a drunken driving accident. At the time of his trial, Couch’s lawyers cited a defense of “affluenza,” claiming the teen’s affluent lifestyle lead to an inability to understand the consequences of his actions.

Many in the media and general public balked at this claim, calling it “junk science” or an outright lie.

Recently, however, research from Arizona State University’s Suniya Luthar, a Foundation Professor in psychologyThe Department of Psychology is an academic unit of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. has been cited as appearing to support the idea that affluent youth do actually suffer from issues such as severe depression and anxiety that can lead to substance abuse and poor decision-making.

A recent blog post co-written by Luthar and Barry Schwartz for Reuters states that although Couch’s “affluenza” defense may just be “an absurd effort to minimize one teenager’s responsibility for a horrific tragedy,” it would be “foolish to allow [it] to obscure growing evidence that we have a significant and growing crisis on our hands."

“The children of the affluent are becoming increasingly troubled, reckless, and self-destructive," they wrote. "Perhaps we needn’t feel sorry for these ‘poor little rich kids.’ But if we don’t do something about their problems, they will become everyone’s problems.”

ASU Now sat down with Luthar to get to the root of this growing problem and talk about ways to deal with and — potentially — prevent it.

Question: Your research has received a great deal of national attention in the past few months, cited extensively in The Atlantic and more recently by NPR, CNN and The Washington Post. Why so much interest now?

Answer: These reports stem from two sets of events recently, one involving the tragic cluster of suicides in Palo Alto, California, and the other being the Ethan Couch “affluenza” case. Essentially, these events capture the types of problems that we’ve repeatedly documented in our research on kids in white-collar, professional families: high rates of depression, anxiety and self-harm on the one hand, and substance abuse and rule-breaking behaviors on the other.

Q: Why are we suddenly seeing so many troubled affluent children? Have they always had these issues, or is this a new phenomenon?

A: Well, we really don’t know what “used to be.” Until the turn of the century, there really wasn’t any research on this subgroup of children in particular.

That said, it is clear that the pressures on these kids have increased tremendously over the last several decades. Competition among affluent youth has become that much stiffer, so that instead of having 200 kids vying for a particular spot in a university, it’s more like 2,000. Between that and globalization, there is so very much more competition, not just for university admissions, but for jobs in prestigious white-collar settings. These factors, I believe, lead to an enormous sense of pressure and, in turn, to high levels of distress among upper-middle class children.

Q: Your research article “I can, therefore I must: Fragility among the middle classes” is among the most-read articles from ASU according to ResearchGate. Does this mean that many more scientists are now studying this population?

A: No, not necessarily. The interest is partly because of the recent media stories, and I think scientists now acknowledge that these problems are in fact real. We have replicated our findings several times across the country.

Despite this acknowledgement, we can’t assume that many more researchers are working with this population simply because these kids are very difficult to access. Most upper-middle class schools are extremely protective about the privacy of their students and families, so that asking to conduct research with them is unlikely to go anywhere. In our case, after our first couple of studies (that happened pretty much by chance), schools started to reach out and ask for assessments, usually after troubling incidents involving serious self-harm or substance use.

Q: What are the solutions to these problems? Are they at all preventable?

A: Yes, I do believe that they are preventable in many cases, but our interventions will have to be at many different levels, as Barry (Schwartz) and I wrote in our recent blog post. Starting with the parents, obviously; it’s critical to keep the channels of communication open with your kids. Teenagers can be notoriously difficult sometimes to get through to, but do keep trying, do make sure your children really do feel loved and cared for, and that you value them for the human beings they are, and not for the splendor of their accomplishments. Also, you have to set your limits and be firm in sticking to them. Kids catch on very fast about whether or not testing the limits will lead to any real consequences from you.

Equally important, parents must understand that they are not machines who can just keep giving and performing; that they too need replenishment if they are to sustain “good enough parenting” in these extremely fast-paced, stressful communities. This is why my recent work is focused on mothers, who are usually the primary caregivers, in efforts to ensure that they too receive ongoing support and tending in their everyday lives.

At schools, teachers need to remember that they are only one of many teachers parceling out tons of homework (often in challenging AP classes). And schools in upper-middle class communities tend to push kids toward a very selective group of colleges — back off that approach. Focus more on conveying to kids that there are many ways in which they can get a splendid college education, show them real-life examples of the many very “successful” people who went to schools nowhere near the Ivy’s.

And there urgently need to be changes in higher education. In our blog article, we reiterated Barry’s terrific suggestion to introduce a lottery system for admissions in highly competitive schools. So essentially, if you have a good enough portfolio to make the top applicant pool, your name gets thrown into the pool but from there on, selection occurs by lottery. This can do much to reduce the enormous pressure kids feel that if they did just one more challenging course or activity, that would make or break their admission.

For more information visit SuniyaLuthar.com.

More Science and technology

ASU to host 2 new 51 Pegasi b Fellows, cementing leadership in exoplanet research

Arizona State University continues its rapid rise in planetary astronomy, welcoming two new 51 Pegasi b Fellows to its exoplanet research team in fall 2025. The Heising-Simons Foundation awarded the…

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s Designing Actionable Solutions for a Secure Homeland student design…

Swarm science: Oral bacteria move in waves to spread and survive

Swarming behaviors appear everywhere in nature — from schools of fish darting in synchrony to locusts sweeping across landscapes in coordinated waves. On winter evenings, just before dusk, hundreds…