ASU student's solution to global malnutrition: A belly full of bugs

Caterpillars are just one of many edible bugs. Others include crickets, beetles and grasshoppers.

Cockroaches, crickets and caterpillars can do more than make your skin crawl. They just might be a tasty and nutritious addition to your next meal.

As part of a global design challenge, Arizona State University biology major Pat Pataranutaporn and a team of student researchers have used biomimicry to design a way to help combat malnutrition. His team created a nature-inspired device called “Jube” — a simple, bug-catching contraption that could dramatically change how humans obtain food.

Pataranutaporn, a sophomore with ASU's School of Life Sciences, and his research team of high school friends from Thailand won second place for their invention in the 2015 Biomimicry Global Design Challenge. The device provides people with an easy way to catch nutrient-rich insects.

The competition asked scientists from around the world to address critical sustainability issues using the principles of biomimicry — designing products inspired by nature. Pataranutaporn and his team were given $7,500 and six months to complete the next part of their proposal.

“Research suggests that insects will be the protein of the future,” Pataranutaporn said. “They have a very high protein content, and they’re a sustainable food source because their populations often exceed an ecosystem’s need for them.

“Sustaining livestock involves wasting a lot of resources,” he added. “So when we say insects are the protein of the future, we’re not talking about individual people suffering from malnutrition. We’re talking about the global community.”

Getting people to eat bugs

But how will Pataranutaporn and his team encourage people to eat bugs?

According to a recent report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, insects already form part of the diets of some 2 billion people. To help those who aren’t already munching on caterpillars, the second part of Pataranutaporn’s proposal involves creating an educational program to teach people how to prepare insects in a tasty way.

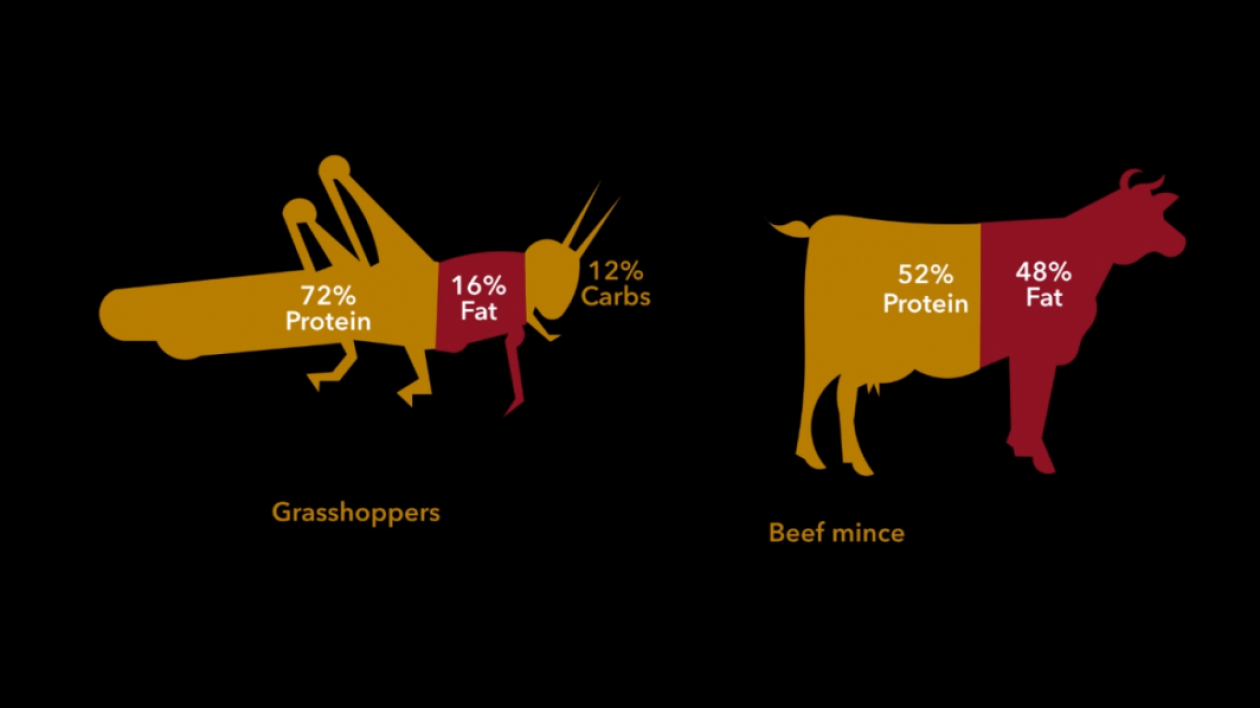

The nutritional facts are convincing. Pataranutaporn’s team found that beef contains 52 percent protein and 48 percent fat. Meanwhile, a grasshopper contains 72 percent protein, 16 percent fat and 12 percent carbohydrates. In addition, it takes far fewer resources to catch insects than to raise livestock.

The challenge of catching crickets

Having found a sustainable and nutritious food source, the team searched for a way to help the average person catch enough insects to provide nourishment.

They looked toward some of nature’s most efficient insect catchers: carnivorous plants. One in particular, the Lobster-pot, uses inward-pointing hairs that make it easy for insects to enter a chamber, but impossible to leave.

Pataranutaporn’s team came up with “Jube” — a device that uses hairs similar to a Lobster-pot’s in a sack filled with insect food. Insects are lured in, become trapped and can be harvested later for consumption.

According to Pataranutaporn, the device is easily made from local materials, and the educational program from their proposal’s next step will include instructions for making a "Jube" at home.

Pataranutaporn said he wasn’t expecting to place in the competition considering his team was up against graduate students and seasoned scientists.

“Those people were real scientists and designers, so I thought it would be super unrealistic to do so well,” Pataranutaporn said. “I was so surprised.”

The next step is preparing for a presentation the team must give at the Biomimicry Institute’s biennial meeting. There, they will be competing against other proposals for $100,000 of additional funding.

More Science and technology

ASU postdoctoral researcher leads initiative to support graduate student mental health

Olivia Davis had firsthand experience with anxiety and OCD before she entered grad school. Then, during the pandemic and as a…

ASU graduate student researching interplay between family dynamics, ADHD

The symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — which include daydreaming, making careless mistakes or taking…

Will this antibiotic work? ASU scientists develop rapid bacterial tests

Bacteria multiply at an astonishing rate, sometimes doubling in number in under four minutes. Imagine a doctor faced with a…