This summer President Barack Obama became the first sitting president of the United States to visit a federal prison, touring one in Oklahoma. He did so at a time when the country’s criminal justice system is under intense scrutiny for its number of incarcerated individuals — though the U.S. represents about 4.4 percent of the world's population, it houses around 22 percentAccording to the International Centre for Prison Studies. of the planet’s prisoners.

“Inmate populations have more than quadrupled since 1969 when the war on drugs began,” said Arizona State University English lecturer Corri Wells.

Considering the sheer number of people behind bars, one of the topics addressed by Obama during his prison visit was the importance of education for inmates.

“It’s a really practical concern, and I think it’s an important one,” agreed Wells.

This spring, Wells took over as director of ASU’s Prison Education Initiatives, members of which were honored Oct. 3 at the Arizona State Department of Corrections' fourth annual Volunteer Appreciation Dinner with awards presented by the Florence and Eyman state prisons.

The program got its start when ASU associate professor of English and former director Joe Lockard (left, with creative writing master’s student Bryan Asdel) began teaching at the Arizona State Prison Complex–Florence in 2009 and realized it might be something his students could benefit from as well.

“Teaching in a prison brings you back to the basics of teaching. There’s no mediated classrooms, there’s no high-tech; it is you, the students and a blackboard, if you’re lucky,” Lockard said. “It is the fundamentals of teaching.”

Addressing a practical concern

The initiative started out as the ASU Prison English program, providing opportunities for mutual learning and engagement between ASU English students and prisoners at Florence.

Interested students would sign up, go through a lengthy and complicated process to be approved to teach in the prison and then head the nearly 60 miles southeast of Tempe to the state prison complex, where they would read stories, have discussions or write with convicted criminals.

Pretty soon, students started coming to Lockard asking about teaching subjects besides English.

Janet Sipes, graduate student and teaching associate in ASU’s School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences, tutors a student in a prison class that teaches eighth-grade to GED-level math skills. Fall 2015 is the first semester that ASU-generated math help has been available to inmate learners. Before this, they struggled on their own to study for the GED and other tests. Four ASU math teachers visit Florence and Eyman state prisons every Friday for two hours at each prison. Photo courtesy Corri Wells

One student, Tina Cai, broached the idea of teaching Chinese. Admittedly, Lockard wasn’t sure how that would fly.

“The prison admin said ‘What? You want to give them a language they can speak and we can’t understand?’” he recalled.

Despite the chilly reception, Lockard pressed on.

“It’s very important to listen to students and their ideas,” he said.

The Chinese course was eventually approved and now maxes out at 29 students, roughly eight of whom have reached the intermediate level.

Cai, now a Columbia University grad student, reported in the 2014 ASU Prison English Project newsletter how even learning a subject as seemingly impractical as Chinese bolstered the inmates’ self-confidence.

“When asked to elaborate on the personal and intellectual rewards of learning Chinese, my students offered variations on a theme: the sense of achievement derived from overcoming intellectual obstacles,” she wrote.

Another student, Anika Larson, expressed interest in teaching biology.

“I asked [Joe Lockard] whether anyone was teaching biology in this particular program,” she said. “They weren’t, but he got the biology class approved and said, ‘If you want to do it, you’ll start in September.’ I panicked, to be honest.”

But with the help and support of School of Life Sciences professor Tsafrir Mor and several doctoral students, Larson got the biology class up and running for the fall 2014 semester.

By that time, the Prison English program had expanded to teaching classes at nearby Arizona State Prison Complex–Eyman as well as Florence. The addition of the Chinese and biology classes — along with others like philosophy and theater — prompted the collective rebranding of the programs as the ASU Prison Education Initiatives.

Gary Garrison and Jacqueline Balderrama — third-year creative writing master’s students at ASU, concentrating in fiction and poetry, respectively — lead a creative writing class discussion at one of the state prison classes. Photo courtesy Corri Wells

The new biology class was to be taught in a supermax facility at Eyman, called the Browning Unit. All of the inmate students arrived in restraints and spent the entirety of the class in individual steel cages.

The conditions added a degree of difficulty for Larson and the other biology teachers, but in the end, the class was deemed a success and was renewed for the 2015-2016 academic year.

Larson called the experience “a highlight” of her time at ASU, and Mor expressed admiration for her “commitment and idealism.”

“I believe that education is a human right that people should not be deprived of, even at supermax security prisons,” Mor said. “Moreover, it is in society’s best interest because providing such opportunities to inmates carries societal dividends.”

Among the benefits to society, Lockard cites the fact that introducing education to inmates significantly reduces recidivism rates.

“There is a very strong bipartisan recognition … that the rate of recidivism is vastly high and needs to be lowered, and education is the answer. It’s unquestionable that education helps prevent recidivism,” he said.

Erasing the stigma

Wells also teaches the course English 484: The Pen Project, a Department of English writing internship and a facet of the ASU Prison Education Initiatives that got its start in 2010 after the initial success of the Prison English program.

The Pen Project remotely and anonymously pairs ASU student interns with inmates in maximum-security prisons in Arizona and New Mexico. The interns coach inmates wanting to improve their writing skills through a process that involves the handwritten work of inmates being collected by prison staff, mailed to ASU instructors, scanned into Blackboard and transcribed by the student interns.

The student interns then read and critically comment on the inmates’ writing. This individualized instruction is edited by instructors of the course, transferred through Blackboard back to the prisons, printed in hard copy and hand-delivered by prison staff directly to prisoners in their cells.

ASU writing interns currently coach about 150 inmates who, together with the interns, produce between 1,500 and 2,000 pages of writing and critique per semester.

“People are dedicated to it; they get a lot of satisfaction from it. It’s very gratifying to know you’re being of service to people who need it,” Wells said.

Jessica Fletcher (left), ASU English undergrad and president of PEAC (Prison Education Awareness Club), and Corri Wells, who took over the Prison Education Initiatives Program this spring, are honored for their volunteerism by the Arizona State Department of Corrections on Oct. 3. Photo by David Wells

Emboldened by the experience, Pen Project student interns organized PEAC (Prison Education Awareness Club), a university club dedicated to teaching students and the community at large about the prison education system.

Wells serves as a faculty adviser for PEAC, which also raises funds for and develops programs to facilitate effective education in the prison system.

Eric Verska, a 2015 graduate of the W. P. Carey School of Business, found out about PEAC through his mother, a retired former employee of ASU’s Department of English.

His interest in the club went deeper than most. A former drug addict, Verska discovered PEAC during his second stint as an ASU student, his first attempt having ended in failure, followed shortly after by a seven-year, drug-related prison sentence.

While incarcerated, Verska found educational offerings to be invaluable.

“That was huge for me. It built my confidence and provided me with the opportunity to continue to pursue [a four-year degree],” he said.

ASU English undergrad and current club president Jessica Fletcher wants to change people’s minds about educating inmates.

“Many treat prison as ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ However … the men and women incarcerated are our neighbors and future coworkers; they are the sons and daughters of friends; they are the mothers and fathers to children in our communities. Just as traditional education is considered paramount to well-being, prison education is vital to the humanity and well-being of prison inmates,” she said.

As part of its awareness mission, PEAC facilitates the Prison Education Conference on campus each spring, with attendees from around the state and keynote speakers from around the country.

The fifth annual Prison Education Conference is set to take place March 19, 2016.

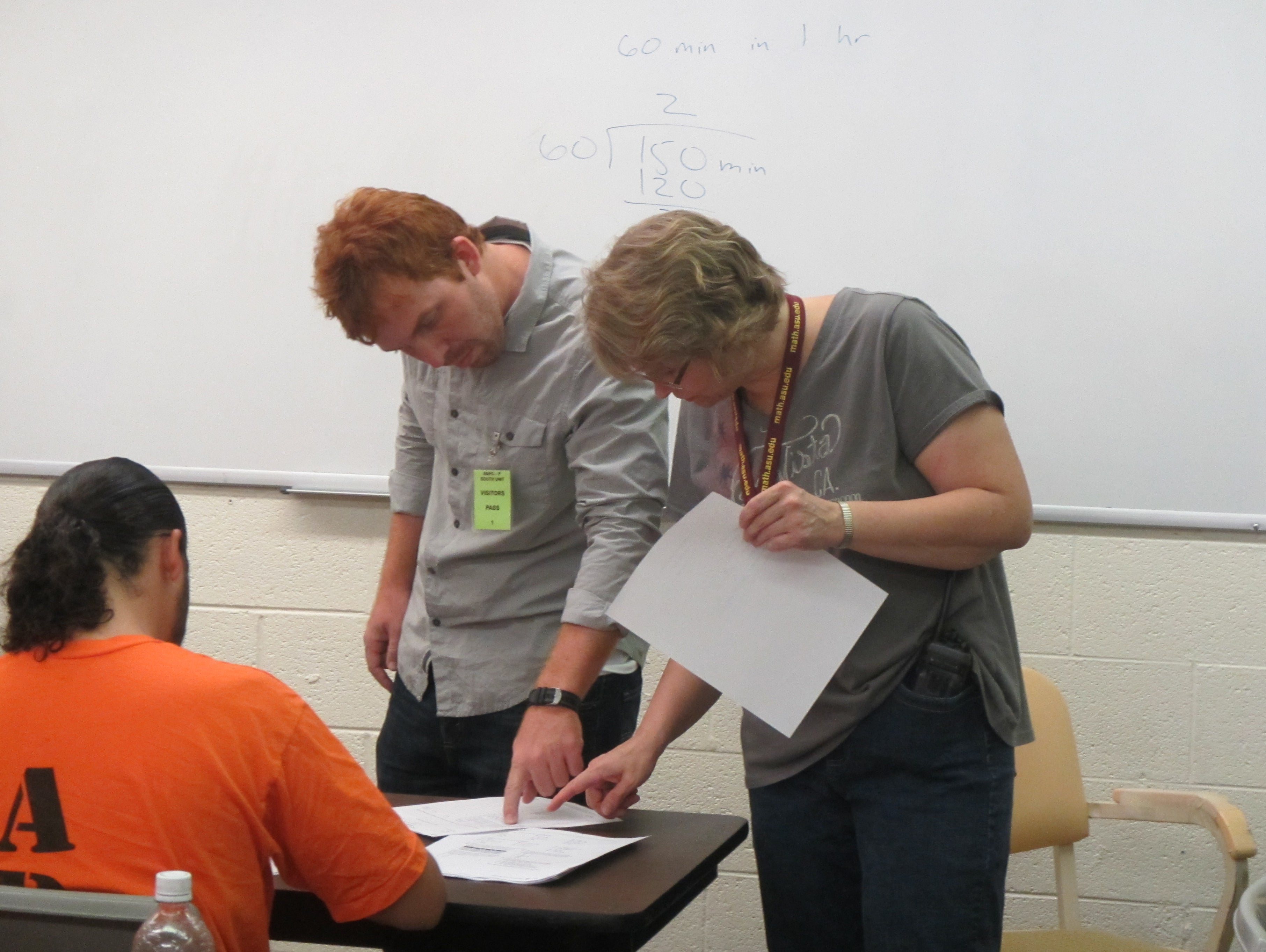

Brent Knutson, ASU School of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences lecturer, and Janet Sipes, graduate student and teaching associate, help a student decipher a math problem. Most of their prison teaching is individualized tutoring like this since math skill levels vary dramatically from student to student. Photo courtesy Corri Wells

A chance at redemption

Former creative writing program manager Corey Campbell taught at the Florence state prison for three years and wrote about it in an introduction to the spring 2015 issue of Insiders, an online journal that features the writing of inmates.

During that time, she developed a bond with her inmate students that gave her a deeper appreciation for their experience.

“I think there’s an undercurrent of despair throughout the prison, throughout the yard, and anything that they can do to engage with the outside world is going to help them and remind them that they are human beings and they are part of the group; they’re not just thrown away somewhere,” she said.

Wells argued a similar point in her introduction to the summer 2015 Prison English newsletter, posturing that what the ASU Prison Education Initiatives and other programs like it offer is more than just a lesson on how to dissect a sentence or solve a math equation — what they offer is a chance at redemption.

“Anyone — even someone sentenced to die in prison for heinous acts like rape and murder, as well as someone convicted of much lesser, so-called ‘victimless’ crimes like drug possession — is capable of life-altering growth and transformation ... to their last breath.”

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…