ASU professor, Arizona inmate work to rehabilitate the 'imprisoned mind'

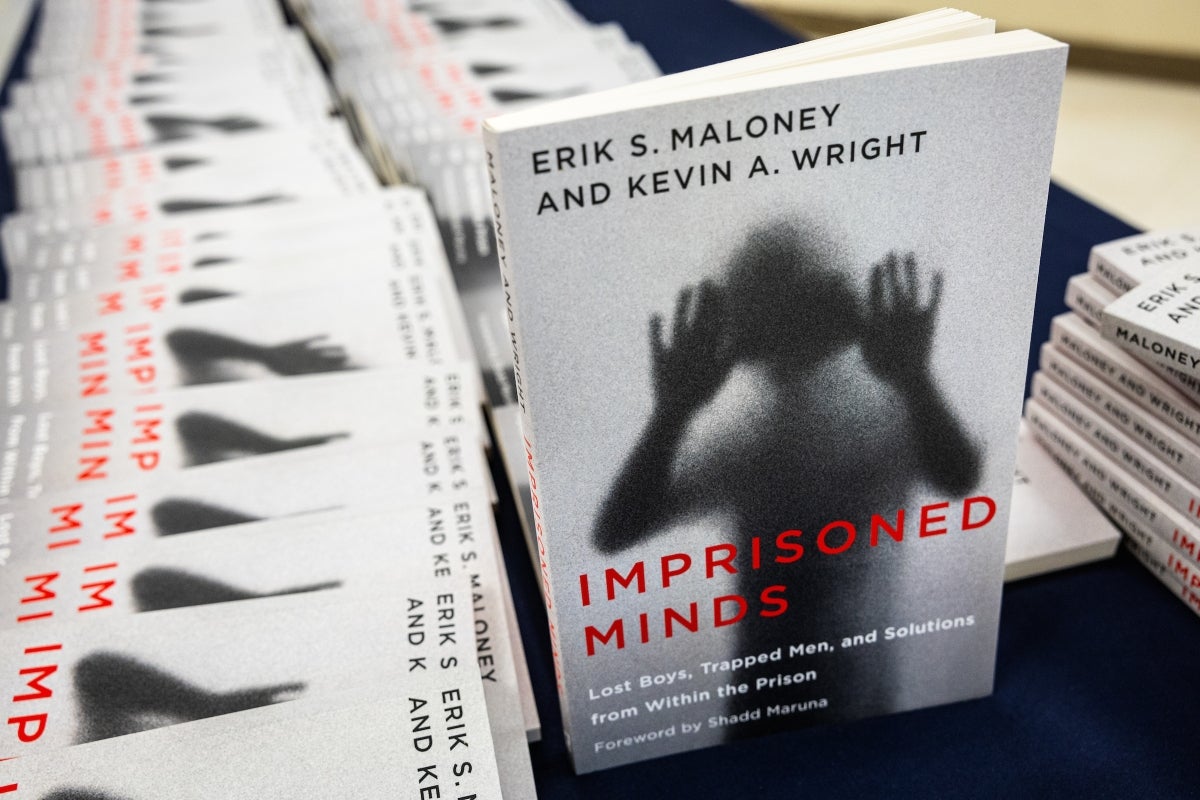

ASU Associate Professor Kevin Wright speaks to inmates, prison officials and guests at a book launch for “Imprisoned Minds: Lost Boys, Trapped Men and Solutions from Within the Prison,” on Tuesday, Jan. 7, at the Red Rock Correctional Center in Eloy, Arizona. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU News

An Arizona State University professor has collaborated with an Arizona inmate on a book that examines why investing in healing prisoners would benefit everyone.

“Imprisoned Minds: Lost Boys, Trapped Men, and Solutions from Within the Prison,” which came out this month, is the result of seven years of work from Kevin Wright, associate professor in the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, and Erik Maloney, who is incarcerated at the Red Rock Correctional Center in Eloy.

The book tells the stories of six incarcerated men who faced traumatic childhoods filled with abuse, neglect and abandonment. Maloney and Wright describe how this background puts young people on a path to “imprisoned minds,” and how a trauma-informed approach in prisons can undo the mindset and help the incarcerated people, prison employees and even victims.

“And this isn't just a small segment of people on the inside,” said Wright, who is director of the ASU Center for Correctional Solutions.

“This is a significant portion of people that are there because of things that happened in their childhood that were unaddressed.”

Maloney, who was sentenced to life in prison in 2000, started reflecting on his past several years ago. In himself and others, he began to see the link between childhood trauma and the development of behaviors that he calls “the imprisoned mind.”

He describes it like this: A child is abused and the trauma is untreated. Distressed, the child doesn’t know how to cope, so turns to drugs and alcohol to numb the emotional pain.

“The individual becomes so focused on achieving this temporary relief that their willingness to engage in criminal endeavors becomes habitual,” he writes.

Maloney says this mindset makes the person hyper-focused on satisfying their own needs.

“The problem with this mentality is its self-deceiving nature: The imprisoned mind causes us to believe that things we simply want are so important that we are required to have them,” he writes.

Maloney believes that prison should focus on reversing the “imprisoned mind” — in part by giving people inside the chance to reflect on their histories, then providing access to counseling and career paths to prepare for life after incarceration.

“(Career guidance) offers the most important ingredient to reversing the imprisoned mind: hope for a better future,” Maloney writes.

In the book, Wright anticipates pushback on a reimagined correctional system that provides trauma-informed treatment, such as the fear of “coddling criminals” and the feelings of victims.

“Most victims usually want two things. Whatever happened to them or their family, they never want that to happen again. And they want people to be held accountable for what they did,” Wright said.

“And we talk about a correctional system where people are held accountable. And so instead of just locking them up and just letting them rot, we say, ‘Hey, you’ve got to make up for this. You’ve got to be productive. You’ve got to give back to the community in some way.’”

Wright wants to change the public perception of incarcerated people.

“When you think of them as humans who are brothers and sisters, mothers and fathers that have families, that are connected to society, and could be again, that's a better approach,” he said.

Putting pen to paper

Wright had Maloney in his first Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program class in 2016 and was impressed.

“He raised his hand and everybody would stop and listen,” Wright said.

In the book, Maloney writes how he faced violence in his childhood that made him aggressive and stunted his personal growth.

“I realized I had deficiencies in how I thought and saw the world, and I recognized the need for me to be better,” he wrote.

He read books, studied religion and talked with others.

“I made a conscious effort to change how I thought and how I reacted to situations.”

Maloney learned qualitative interviewing techniques through the Inside-Out courses, but didn’t think anyone would be interested in a book from an incarcerated person with no degree, so he pitched the idea to Wright.

“I immediately said yes, just simply because he was such a great student in class, and I wanted to support him in his work,” Wright said.

“And the more I got into the project and read the stories, I was like, ‘This is going to be impactful and people need to read this.’”

They collaborated mostly through letters, meeting occasionally, with long delays caused by the pandemic and Maloney’s prison transfer.

Recording devices are banned, so Maloney took notes with a pencil, spending hours talking to the men in their cells or in the prison yard.

He chose men whose stories highlight the development of an “imprisoned mind” — who had dealt with abuse, drug use and poor decision-making growing up. One man was conceived when his parents were in the same prison. Another was separated from his four siblings after his mother took her own life.

One inmate, called “Sergeant,” a veteran of the Iraq war, grew up in a violent household and struggled to adjust after he was badly injured and medically discharged. He was with a friend when they saw a mini fridge in the back of a truck.

“For some reason, I got it in my head that I wanted it,” he told Maloney.

Sergeant was shot by an off-duty police officer during the robbery. He was charged with first-degree murder because his friend died in the shooting.

Along with the trauma, the men also recalled loving family members and periods of stability and success.

Both authors knew that some people would think the work isn’t scholarly enough, but Wright disputes that.

“What does it look like if we center lived experience and lived-experience methods and roll with it?” he said.

The stories in “Imprisoned Minds” are part of a trend of listening to the people involved in the justice system. “Participatory action research” shifts the focus away from an academic researcher driving the narrative and toward working with the “credible messengers,” Wright said.

The authors also want people to know what correctional system employees are up against.

“I want the general public to see that when you think the system is broken or you get frustrated that recidivism rates are high, this is years and decades of trauma, of victimization, of substance abuse and mental illness that we can't fix overnight and we can't fix with just criminal justice solutions,” Wright said.

“I'm hopeful that this will indirectly humanize and normalize the corrections profession a little bit too, when they see how challenging and how complex it is to care for the people under their watch.”

POINTing the way

The ASU Center for Correctional Solutions is already working with the Arizona Department of Corrections, Rehabilitation & Reentry to reimagine prisons.

The center's POINT Model, for “Potential, Opportunity, Investment, Nurture, Transformation,” is one way of investing in the improvement of life inside. The model is providing ASU resources — people, programs and workshops — at two sites: the Red Rock Correctional Center and the women’s prison, in Perryville.

For example, incarcerated women in Perryville have described the challenge of processing grief and trauma while behind bars.

“If you lose a loved one while in prison, there’s very limited support of how to work through that,” Wright said.

So Joanne Cacciatore, a professor in the School of Social Work who researches traumatic grief, ran a workshop at Perryville, leading the participants to create a grief and trauma tool kit. Wright is working to have the women become virtually certified.

“So it's really taking the ASU Charter and the principles behind it, and also our design aspirations, and applying it to a better correctional system in Arizona,” Wright said.

“It’s no longer an all-knowing university saying, ‘Hey, this is the theory, this is the data, we're going to come in and we're going to do it.’

"Instead we’re saying, ‘How can we support people in here?’ Then we’re learning the challenge and saying, ‘What do we have at ASU in terms of people and programs that can help address it?’”

More Arts, humanities and education

Local traffic boxes get a colorful makeover

A team of Arizona State University students recently helped transform bland, beige traffic boxes in Chandler into colorful works of public art. “It’s amazing,” said ASU student Sarai…

2 ASU professors, alumnus named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows

Two Arizona State University professors and a university alumnus have been named 2025 Guggenheim Fellows.Regents Professor Sir Jonathan Bate, English Professor of Practice Larissa Fasthorse and…

No argument: ASU-led project improves high school students' writing skills

Students in the freshman English class at Phoenix Trevor G. Browne High School often pop the question to teacher Rocio Rivas.No, not that one.This one:“How is this going to help me?”When Rivas…