Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

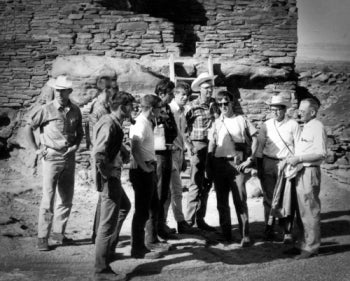

Donald Johanson at the Lucy discovery site in Ethiopia on Nov. 24, 1974. Photo by Bobbie Brown

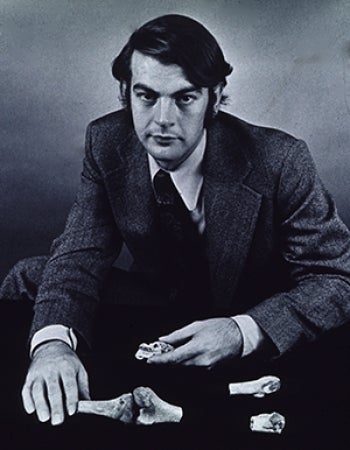

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2 million-year-old human ancestor “Lucy.”

Lucy in the spotlight with diamonds

Explore coverage of the anniversary celebration at news.asu.edu/spotlight/lucy-at-50.

This small creature is important to the human lineage because it is the first evidence of our ancient predecessors who walked upright all the time — obligate bipeds.

In the 50 years since Lucy was discovered, the importance of this discovery has not diminished, but has fueled expansion of the search for how we “became human.”

ASU News sat down with Johanson, founding director of the Institute of Human Origins and Virginia M. Ullman Chair of Human Origins with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, to talk about how he became interested in science, the Lucy discovery and what's next for Lucy’s lasting legacy.

Question: How did you become interested in science?

Answer: When I was in elementary school, Noah Webster Elementary School in Connecticut, I had an enthusiastic teacher, Mr. Julian, who was excited about basic science; he really inspired me. I became fascinated with the scientific world. I was then fortunate to meet an anthropology professor who lived nearby — Paul Leser. My father died when I was 2 years old, and I never knew him, but this man gave me the greatest gift in the world — he gave me access to his library. He had books from the floor to the ceiling in every room in his house, and said, "Read what you want."

As a kid, one of the questions we ask is, "How did we get here?" And Professor Leser pointed me to a section on what was then called physical anthropology, now biological anthropology, and a thin little book by Thomas Henry Huxley from 1863 called "Man's Place in Nature." Its basic premise is that we had a common ancestor with chimpanzees. This was my moment of enlightenment. I decided I wanted to be an anthropologist and go out and search for fossils.

Q: Why did you go to Africa to look for fossils?

A: As an undergraduate student studying anthropology and geology, I discovered that at the University of Chicago, Professor F. Clark Howell had led expeditions to Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania. I knew that Professor Howell was never going to knock on my door and say, "Hey, want to go to Africa with me?" So I called him and said, "You don't know me, but I'm a student at the University of Illinois, and I'd like to come and meet you." I went to meet him, and I was able to study with him. Professor Howell took me to Africa for the very first time and sat with me at the tables in the field sorting fossils and contributed so much to my knowledge.

Q: What did you expect to find in Africa?

A: My answer is always “the unexpected.” I've had the extraordinary opportunity to work in Africa beginning in 1970. In 1972, I was working closely with a French geologist named Maurice Taieb. We were exploring an area that was literally “terra incognita” — the northeastern part of Africa's Great Rift Valley, a place known as the Afar Triangle. It was absolutely littered with fossil bones that we knew were older than 3 million years in age. But we were hoping to find remains of our human ancestors. We had just fragments of hominin fossils from other sites in the Rift Valley.

The first indication that there would be human ancestor fossils at this site of Hadar in the Afar region was a discovery I made in 1973, which was the discovery of the first fossil human in this region — a knee joint. It was the bottom end of the thigh bone and the top end of the shin bone. The anatomy of that knee joint showed us, without a doubt, that this was a creature that walked upright. It had all the features of bipedality, which was very important, but we didn't know what species it belonged to. This spurred us on to return in 1974 to see if we could find more complete remains of early humans. That knee joint was found only a few kilometers away from where Lucy was discovered a year later.

Q: How did you find the Lucy fossil skeleton?

A: In 1974, on our second expedition to this area, I was out surveying with one of my graduate students, Tom Gray. A complete pig skull had been found in this area, and we were there to position it exactly on our maps.

As we looked around that day, there weren't many fossils. It was noon and getting to be 110 degrees. We were tired and heading to the Land Rover to go back to the field camp. I looked over my right shoulder — I'm always looking at the ground — and saw a little fragment of an elbow. I recognized it as not being a monkey or an antelope or any other mammal. As I turned it over, I saw the anatomy so distinctive of a human skeleton, of a human ancestor skeleton. And as I looked up the slope, I could see other parts of a skeleton — part of a femur or thigh bone, chunks of mandible, shards of a cranium. I realized that there was a partial skeleton here!

We knew from the geology that the fossil was older than 3 million years. It turned out that Lucy is 3.18 million years old and comprises about 40% of a single skeleton — still the most complete adult Australopithecus afarensis species skeleton. The fossil is popularly known as Lucy, named after the Beatles song “Lucy and the Sky with Diamonds,” which was playing in camp that night of the discovery. I thought that she was a female because of her diminutive size. And someone suggested, "Well, why don't you call her Lucy?" And it stuck.

In many ways, Lucy has become the touchstone for people who become interested in paleoanthropology — the study of human origins — and arguably is probably the best-known fossil human ancestor of the 20th century. That day was Nov. 24, 1974, incidentally the same date that Charles Darwin's "Origin of Species" was published in 1859. It took me two months in the field to find this fossil, but there at my feet was my childhood dream.

Q: After 50 years, what do we know about Lucy and the impact of that discovery?

A: For Lucy, she was only three-and-a-half feet tall and an adult, because her third molar, or wisdom tooth, had erupted. She probably died when she was quite young, around 9 or 10 years old — her species matured much more quickly than we do. The species named in 1978 — Australopithecus afarensis — is remarkably important for a number of reasons. One is that we now have almost 500 individual specimens of her species collected over the past 50 years, and so that provides us with a comprehensive collection of Australopithecus as a yard stick for evaluating other ancient hominin species.

When we began working in Hadar, Ethiopia, in 1972, we were the only team that was working in the Afar. Today, there are numerous expeditions working in the Afar. I'm proud to say that several of those teams are led by Ethiopians who now have their PhDs and are undertaking field research on their own, helping us fill in the exciting record of how we became human.

In fact, the Institute of Human Origins at Arizona State University has two additional research sites in that area — Ledi-Geraru, where the earliest evidence of our own genus Homo was discovered by one of (the institute's) research teams in 2013, led by ASU Emeritus Professor Kaye Reed, and Woranso-Mille, a research site led by Institute of Human Origins Director Yohannes Haile-Selassie that shows evidence of several species sharing the same landscape during the same time period 3 to 4 million years ago.

In 1974, the National Museum of Ethiopia was not prepared to store and process these fossils. The success of expeditions in Ethiopia, not just the ones that we had to Hadar but others as well, attracted a great deal of funding to build facilities in Ethiopia — some from the National Science Foundation and other sources. So facilities were built in the museum where fossils and artifacts could be stored safely. Local assistants were hired to help clean and organize the fossils. The National Museum of Ethiopia has, over the last 15 to 20 years, invested an enormous amount of money in building a large building to store these fossils — not just fossils of our human ancestors, but tons of fossils of elephants, pigs, rhinos, monkeys, antelopes and other animals.

And everyone does compare new discoveries to Lucy: "Is this new discovery before or after Lucy? How does this species compare to Lucy's?" The last evidence of this species is also the pivotal point on the family tree where there's significant climate change. This species disappears about 3 million years ago when there is a change to a more open environment and a change in the composition of the animals that suggests more open areas. It signals the end of her species and the beginnings of two major lineages — one that ultimately led to us, Homo sapiens.

Q: Is Lucy the missing link?

A: For me, all of them were missing links until we found them. But they remind me of our link to the natural world and that these creatures like Lucy were living under natural conditions. They were part of that landscape, integrated into that landscape and closely tied to that landscape, to the natural world. And today, humans have lost that understanding of our connection to the natural world. Even though we have incredible technology, we were crafted by the natural world. We need to develop more of a reverence for the natural world and make responsible decisions about how we treat the natural world so that we will leave descendants who will look back on their ancestors.

It is important to understand our past and to understand how we came to be who we are today. When we look at that in the bigger picture of mammalian evolution, 99.9% of all species that lived went extinct — is extinction our destiny? How long can we prevent that from happening?

Every human on this planet today has a common origin. No matter where you grab a branch on that family tree, the roots lead back to Africa. In essence, we are all Africans. We look different from one another superficially, but in terms of our genetics, we are all Africans. And if we accept the notion that we have a common origin, a common past — it's inescapable that we have a common future.

The Institute of Human Origins here at Arizona State University has become a recognized focal point for understanding how we became human. It's the personification of the multidisciplinary approach of geologists, paleontologists, anatomists, anthropologists, geneticists and so on. Students from around the world are attracted to studying here because they want to know more about our past. They want to know more about how early humans moved around the planet that's being tracked through genetics, for example. They want to understand why Lucy’s skeleton looks different from other skeletons. Arizona State University is a model for this transdisciplinary research that is necessary for understanding how humans came to be.

We're hoping that this 50th anniversary celebratory year will reignite a worldwide interest in human origins. The study of human origins has never been as vibrant as it is today.

Learn more about Lucy

- View a half-hour program from Arizona PBS about Lucy's lasting legacy.

- Explore the "Finding Lucy" exhibit at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change Museum of the Human Story, Monday–Friday during business hours through Feb. 28, 2025.

More Science and technology

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your health history in five-inch stack of paperwork fastened together with…

Large-scale study reveals true impact of ASU VR lab on science education

Students at Arizona State University love the Dreamscape Learn virtual reality biology experiences, and the intense engagement it creates is leading to higher grades and more persistence for biology…