ASU collections offer Indigenous perspective through traditional storytelling, innovative methodology

Vina Begay, assistant librarian and archivist, showcases items from the Labriola National American Indian Data Center’s contemporary collections at the Fletcher Library at ASU's West Valley campus on Oct. 8. Photo by Deanna Dent/Arizona State University

Editor’s note: This is part of a monthly series spotlighting ASU Library’s special collections throughout 2024.

Cultural archives are usually organized in a way that reflects the perspective of those who administer the collection.

With Arizona State University’s Native-led Labriola National American Indian Data Center, the archival team is working to change long-held practices by incorporating Indigenous ways of knowing into archival applications.

See the collection

For questions about or to view materials in the Labriola Center Collections, reach out to the ASU Library’s Ask an Archivist service.

“When dealing with our Indigenous collections, we must incorporate our perspective into our processes through a lens of cultural inclusivity and representation,” said Vina Begay (Diné), an assistant librarian and archivist for the ASU Library’s Labriola Center at Fletcher Library on the West Valley campus, where researchers can make appointments to view the collection. “We must acknowledge that Indigenous people are different in terms of how we look at information, how it’s assembled, and make sure that our stories are told accurately throughout history.”

An endowed literary and manuscript collection dedicated in 1993, the Labriola Center collects current and historical information to support the American Indian curriculum at ASU and is dedicated to collecting and providing access to Indigenous knowledge. The center serves the ASU Tempe and West Valley campuses through material access, collaborations and outreach.

It also provides resources to support ASU student and faculty academic success, including the preservation and curation of Indigenous knowledge and awareness. The overall collection contains manuscripts, oral stories, political papers, photographs, ephemera and contemporary books written by Indigenous scholars, authors and artists.

It’s also a major source of Indigenous pride and resilience, according to Candace Hamana.

“As an Indigenous-led repository, the Labriola Center is a powerful reflection of the pride and resilience of Native communities. It honors our stories through the thoughtful preservation of traditional knowledge alongside contemporary narratives,” said Hamana (Hopi), director of tribal relations at ASU. “By integrating digital tools with Indigenous methodologies, the collection offers innovative ways to access and share our histories, ensuring they remain preserved for future generations. This work enriches ASU by providing students, faculty and the broader community with meaningful access to Indigenous perspectives, shaping a more inclusive and forward-thinking academic environment.”

In observance of National Native American Heritage Month, celebrated throughout the month of November, we look at the rich variety of materials in the collection that showcase a selection of Indigenous individuals, movements and histories that have made an impact in Arizona and the Southwest.

Jean Chaudhuri Papers 1970–1997

Native American activist Jean Chaudhuri (Muscogee Creek Nation) died at the age of 59 but lived several lifetimes. Her life sounds like a motion picture — and that’s exactly how Begay wanted to convey this collection of papers.

“This collection is arranged completely different from a Western practice in how it’s arranged and described,” said Begay, who was hired by ASU in 2022 and has a theater and storytelling background. “So, in that storytelling, we are weaving a link rather than offering a beginning, middle and end. It’s telling a story from a lived experience.”

Wise beyond her years, Chaudhuri accomplished so much in an era when Indigenous women were not given opportunities to express their voices more broadly. Chaudhuri’s sheer will and perseverance managed to thread the needle when it came to government red tape and roadblocks.

Wherever she lived, she was involved in some aspect of community service — from running for office to protecting Native American’s religious freedom in the Arizona corrections system to setting up a health clinic in Tucson — she was a force of nature that could not be denied.

The Jean Chaudhuri Papers is 12.5 linear feet, and contains journals, correspondence letters, research for various projects, creative writings, newsletters, photographs and documents for Arizona Indian Women in Progress, Traditional Indian Alliance, Phoenix Indian School Support Team, Native American Preservation Coalition and the Native American Religious Advisory Council.

Yitazba Largo-Anderson (Diné) is a program coordinator with the Labriola Center and helped Begay process the collection. She said it was a life-changing experience.

“Organizing the collection was hard because it was very large and overwhelming,” Largo-Anderson said. “Jean Chaudhuri wasn’t just an activist but a mom, a playwright, an author, a director, an artist and the founder of an urban clinic. Vina found a very respectful way to tell that story from an Indigenous storytelling perspective.”

Largo-Anderson said working on the collection helped to put her more in touch with her roots and her career.

“I’ve had other experiences where I didn’t see myself as an Indigenous person within the library system,” Largo-Anderson said. “But working with the staff at the Labriola Center helped me become more open and willing to pursue a library degree. I feel like I’ve found my home.”

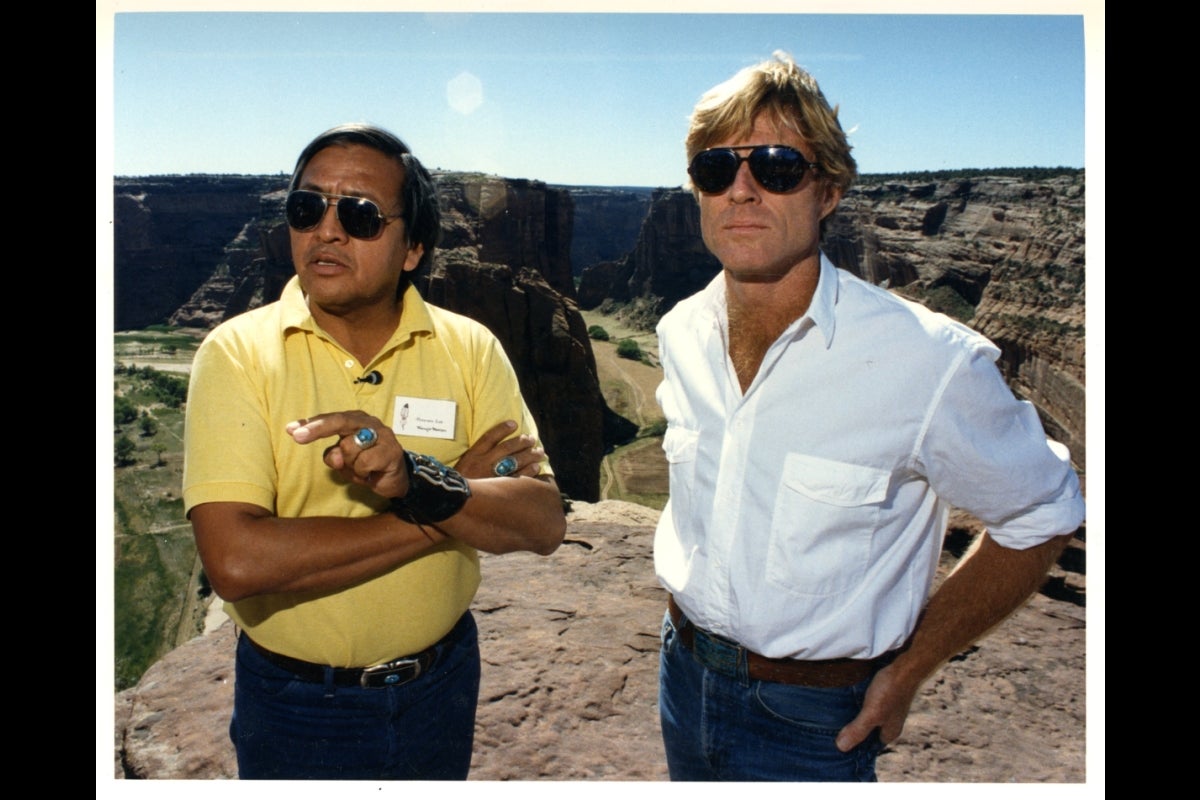

Peterson Zah Collection 1969–1994

More than six decades ago, when ASU opened the Center for Indian Education, the university had 17 Indigenous students enrolled at the university.

Peterson Zah, a chairman and the first president of the Navajo Nation and the first special advisor to the president on American Indian affairs at ASU, first attended the university in 1959. He said getting to ASU was an adventure and an education in life.

Zah packed his luggage — a brown paper sack — placed his clothes and whatever possessions he owned in it, and hopped in the back of a pickup truck, commandeered by his uncle with his aunt riding shotgun.

“On the way down from the reservation, we stopped at a store in Payson to eat and gas up,” Zah told ASU News a few years before his death in 2023. “I could barely read or speak English, but I noticed a sign in the window that read, ‘Any good Indian is a dead Indian.’ I asked my uncle what that was about. He shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘People are just that way around here.’

“I asked him, ‘What am I going to school for?’” Zah said.

Soon he would find out — to help build capacity for his people and other tribes. When Zah graduated in 1963 with a degree in education, his trajectory ascended steadily upward. He taught high school in Window Rock, worked as a construction estimator for the tribe, did a stint with the AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer program and helped the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe build the one of the earliest major Indian casinos in Ledyard, Connecticut.

Between 1967 and 1981, Zah served as executive director of the nonprofit organization DNA (Diné be’iina Nahiilna be Agha’diit’ahii) People's Legal Service in Window Rock. During his decade of directing DNA, he succeeded in having several legal cases establishing Indian sovereignty reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 1995, Zah was hired and tasked by then ASU President Lattie Coor to look for innovative ways to increase the number of American Indian students at ASU. He served until 2011 and saw the Native student population double. This semester, ASU has 4,130 American Indian students who have self-reported their identity.

The Peterson Zah Collection measures 44 linear feet and is one of the largest in the repository. It contains professional papers, correspondence, newspaper articles, photographs, audiovisual material and artifacts dating from 1969 to 1994. The bulk of the material dates from 1982 to 1990 and consists of papers showing Zah's time campaigning for and acting as chairman, and later president, of the Navajo Nation.

Jacob Moore (Tohono O’odham Nation), ASU’s vice president and special advisor to the president on American Indian affairs, knew Zah for years. He said having his papers housed at ASU is an honor.

“Peterson Zah was a visionary leader whose lifework included major positive impacts for the people and the governance of the Navajo Nation. Following his years in tribal government and as ASU’s first special advisor to the president, Dr. Zah also played a major role in helping the university create new programs, including Construction in Indian Country, the American Indian Studies program, American Indian Student Support Services and others,” Moore said. “As a persistent advisor, Dr. Zah helped President Crow shape ASU into an institution that currently has the highest enrollment of Native students of any major university in the country.

"Being able to house and maintain the Peterson Zah Collection at ASU is an honor and provides students the opportunity to better know his legacy and to learn from his experience as an outstanding advocate for Indian country.”

Simon J. Ortiz Papers 1946–1992

Readers of RED INK: International Journal of Art, Literature, and Humanities have Simon J. Ortiz to thank for not only keeping it afloat but bringing it to Arizona State University. The journal is a celebration of Indigenous life and art. But Ortiz is best known as a poet, fiction writer, essayist and storyteller.

The retired ASU Regents Professor of English and American Indian studies has also worked on scripts for several video projects, some of which were produced as TV shows or documentaries. Most of his work focuses on issues that currently affect Indigenous peoples.

The main themes among Ortiz's work and mentorship of others involve continuance, centering Indigenous voices and recognition of American Indian literature as its own national canon.

“Simon Ortiz is among the greatest Native American literary figures of his generation. He broke down walls for more Indigenous voices and culturally relevant Indigenous experiences in Native American literature. He laid down that foundation for Indigenous writers today,” Begay said. “It brings me joy that he donated his collection to ASU. I learned of Ortiz’s writing as an undergraduate student. Now as an archivist, there is something so powerful interacting with the original manuscripts within his collection. I tend to geek out because all his work has become a Native American literature classic.”

Ortiz created and founded the Indigenous Speaker Series at Arizona State University. He has also been awarded the following: the Lila Wallace Reader's Digest Writer's Award, the New Mexico Humanities Council Humanitarian Award, the National Endowment for the Arts Discovery Award, a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and was an honored poet at the 1981 White House Salute to Poetry. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Returning the Gift Festival of Native Writers.

The Simon J. Ortiz Papers contain his writing, journals, correspondence, projects, Pueblo of Acoma work, teaching materials, research, miscellaneous files, conference materials and audiovisual material. The bulk of the material dates from 1960 to 1992 and consists of his writing, research and correspondence.

American Indian Movement (AIM) of Arizona Records 1954–1998

The American Indian Movement was formed in 1968 in Minnesota. This grassroots organization quickly brought attention to itself through a series of protests and actions in response to police brutality, racial profiling and high unemployment.

They drew worldwide attention for their occupancy of Alcatraz prison in 1969. Later, they became involved in the deaths of FBI agents and two Native Americans during a standoff at Pine Ridge, South Dakota, in 1975.

At one point, the Federal Bureau of Investigation deemed AIM an “insurgent guerilla terrorist group,” but it is now recognized as the driving force behind the Indigenous civil rights movement.

“In the 1970s, (AIM) could be considered extreme, but now with new leaders in place, it has changed and shifted,” Begay said. “They continue to focus on Indigenous rights and policies, environmental issues, and eliminate stereotype tropes, such as mascots.”

This collection, which is about 8.5 linear feet, houses correspondence, photographs, newspaper clippings, videotapes and other materials documenting the American Indian Movement in Arizona. This includes the controversy surrounding Leonard Peltier, mascots, the changing of the name of Piestewa Peak (from its former name, "Squaw Peak") and social community gatherings.

Open Stacks Collections

The Labriola Center’s Open Stacks Collection is robust and varied, and considered by many as a national standout. Filled with thousands of volumes, these books touch on a variety of Indigenous topics that range from food sovereignty to language revitalization to silver work to treaties.

Materials in this collection feature titles either authored by or for Indigenous peoples. All titles promote and support Indigenous academic excellence for all disciplines.

“This collection includes Indigenous writers, poets, filmmakers, lawyers and scholars who are doing work in their field,” Begay said. “It shows that we are everywhere. We are not silent or extinct. ... These are people from the past and present who are doing contemporary work.”

Begay said the collection continues to grow by leaps and bounds. However, that is not the first priority of the Labriola Center.

“Our focus is meeting the needs of our students, incorporating community voices and decolonizing practices towards library information,” Begay said. “The Labriola Center is setting the stage to become a model for all of those things.”

It’s certainly become a model for Nataani Hanley-Moraga (Diné/Húŋkpapȟa Lakota/Chicano), who as a Knowledge River Scholar is part of a master’s program for Indigenous, Latino and BIPOC students seeking to enter the library profession.

“It’s been eye-opening for me to work on this collection because it has showed me how important it is to document our Indigenous history and advocate for our stories,” Hanley said. “The storytelling method Vina has implemented really shows the impact and magnitude of Native American history. ... It’s inspiring.”

Monthly series spotlighting ASU Library’s special collections

- January: Expanded Theatre for Youth and Community Collection remains a repository for emerging artists and educators

- February: Black Collections aims to document the lives of an underrepresented Arizona community

- March: Voices from Latin America can be found in dynamic research collection

- April: Thunderbird archives: These walls do talk

- May: Collection preserves legacy of modern architects, buildings in the Southwest

- June: LGBTQ+ Studies Collection a repository rich in legacy

- July: Pop-up book collection is deceptively simple fun

- August: A (re)source of Sun Devil pride

- September: Chicano/a Research Collection filled with action, education and activism

- October: ASU collections offer Indigenous perspective through traditional storytelling, innovative methodology

- November: University Archives chronicles more than 140 years of Sun Devil history

- December: Collection captures the robust history of Arizona

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor's project helps students learn complex topics

One of Arizona State University’s top professors is using her signature research project to improve how college students learn science, technology, engineering, math and medicine.Micki Chi, who is a…

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming Awesome," with actors at Arizona State University this week. “I want…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops, entertainment venues and inviting spaces that beg for attention from…