Arizona governor: Cross-border collaboration is more important than ever

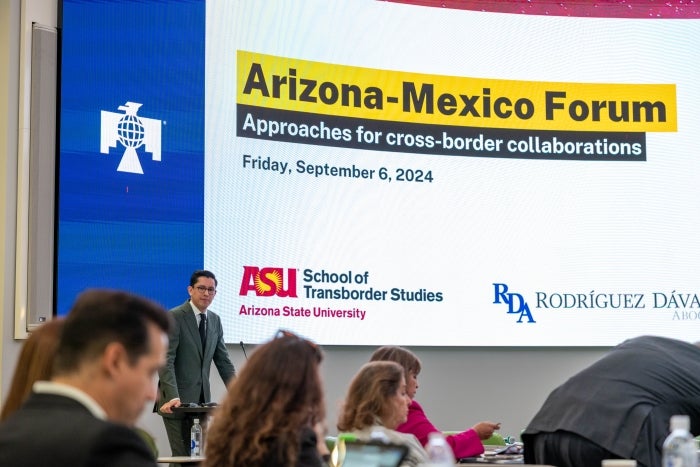

Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs speaks at the Arizona-Mexico Forum on Friday. The event was put on by ASU's School of Transborder Studies and co-orgonized by the Mexican firm Rodríguez Dávalos Abogados. Photo by Dustin Davila-Bojorquez/ASU

It was a little after 9 a.m. last Friday when Irasema Coronado, the director of Arizona State University’s School of Transborder Studies, began her remarks.

Nearly 100 people had gathered at Thunderbird School of Global Management for the Arizona-Mexico Forum, where academic and industry leaders from both sides of the border would examine ways to boost cross-border collaborations.

There would be five panel discussions: Nearshoring; water and environmental issues; energy; investment and infrastructure; and workforce development and labor mobility.

But for Coronado, the discussion was personal.

She talked about how she grew up in Nogales, Arizona, and how her father was the Holsum bread distributor for Santa Cruz Country. Nearly every day, she said, her family would cross the border to provide hot dog and hamburger buns to businesses.

“I remember the immigration inspector greeting my mother and saying, 'Mrs. Coronado, other than your six children, what are you bringing from Mexico today?’” Coronado said. “We would cross the border several times a day. It was very common back then.”

Coronado lamented the fact people today don’t have the same experience she had as a child and hoped that the forum would lead to more collaboration between Arizona and Mexico.

Arizona Gov. Katie Hobbs, speaking before Coronado, said that collaboration is more important than ever given Arizona is one of the largest recipients of CHIPS funding and is at the “forefront of the American manufacturing resurgence, namely in advanced package and semiconductor manufacturing.”

“So many aspects of our cross-border region are intertwined,” Hobbs said. “This is such an area of important partnership for both our countries and this region. Our geographic proximity provides seamless access to manufacturing hubs and reducing costs, and our decades of collaboration have created efficient production and distribution pathways.

“These areas are a gateway to a brighter future for all of us, and our partnership with Mexico is critical to this as well.”

The first panel of the day examined the possibilities and challenges of nearshoring, a business strategy that involves moving some or all of a company’s supply chain operations to a location close to its main market.

Thomas Maynard, senior vice president of business development for the Greater Phoenix Economic Council, said three components are critical for nearshoring: workforce development, infrastructure and bridging cultural differences.

“As an example, you could have an engineer and a non-engineer talking to each other in the same language, and they're still talking over each other,” Maynard said.

Veronica Villena, the Loui Olivas Chair in Management of the W. P. Carey School of Business, said it’s important to consider sustainability when it comes to nearshoring practices.

“We want to have more business from Mexico here in Arizona, but I wonder whether this increased amount of capacity will have some negative impact to the environment,” Villena said. “I think when we talk about supply chains, we need everybody to talk about sustainable supply chains. So how can we work with factories, especially in Mexico, to make sustainability part of their culture?”

Water and environmental issues were the subject of the second panel, headed by Sarah Porter, director of ASU’s Kyl Center for Water Policy. Porter asked the panelists what they see as the primary challenge to building Arizona-Mexico collaborations.

Luis Antonio Rascon, part of the Mexican section of International Boundary and Water Commission, said the primary obstacle is how to provide water given demand along the border is increasing and supply is decreasing.

“On top of all that, we have all the uncertainty of climate change,” said Francisco Lara-Valencia, a professor in the School of Transborder Studies. “We are in a situation in which the very delicate balance between demand and supply is at risk, so we need to find ways to address those challenges.”

Porter put it simply:

“There’s a people element to this problem. It’s not all pipes and pumps,” she said.

Abraham Zamora, chairman of the Mexican Energy Association, said in the energy panel that it’s vital Mexico and the United States take a regional approach to shared energy to overcome the difference in regulations: In Mexico, he said, energy is regulated at a federal level, while in the U.S., it’s regulated at national and state levels.

“I believe that we have a very good opportunity to see more integration between the U.S. and Mexico in the energy sector, but we need to have a regional view that can benefit both countries,” he said. “We have to see the region as one policy in the energy sector.”

Kenneth Ulrich, director of business development for Kinder Morgan NGP West Region, said education of the public is needed as well.

“There is environmental disturbance involved in building pipelines, building gas storages and building power plants,” he said. “So people need to know where their energy comes from, just like we need to know where our food comes from and where our water comes from.

“A broad discussion needs to take place not just at the project level, but it’s talking to state and federal governments, the stakeholders, the communities that you’re in and the customers. You have to convince the public there’s a need here.”

Miguel Sigala, a graduate research aide in the School of Transborder Studies, said in the labor mobility panel that universities such as ASU can be “strategic agents to developing workforces.”

One way to do that, said Sean Manley-Casimir, director for Hemispheric Programs at the University of Arizona, is to create economic conditions that encourage students to study in a different country.

Manley-Casimir pointed out that Mexico pays educational costs for its local and national college students. Why, he said, would American students then “pay a high amount of money to go to another country when the students sitting beside them are having the government subsidize their education? How do you convince them the value is there?”

Manley-Casimir said he’d like to see the United States and Mexico — as well as other countries — create pools of empty seats that would be subsidized by scholarship money.

“Those policies between Arizona and Mexico on student mobility are a very important part of what we will be working with when it comes to semiconductors,” said Jorge Mendoza Yescas, General Counsel of Mexico in Phoenix. “Mexico and the region need to seize this moment. There’s a lot of interest in relocating the process of semiconductors in border states like Sonora and Chihuahua. There’s a five-year window of opportunity to do things that need to be done, and that’s to create policies on the movement of goods and people.”

More Local, national and global affairs

Higher education key to US competitiveness, security

ASU President Michael Crow’s notion of universities as public service institutions — places that serve society in practical and meaningful ways to solve pressing issues of importance to the country…

Military program leaders learn about breadth of ASU's defense-focused initiatives

Arizona State University seeks to be the U.S. military’s top partner in strategic learning and innovation. To advance this vision, the Office for Veteran and Military Academic Engagement hosted…

Expert discusses America's place in outer space with ASU students

If you asked Esther Brimmer about what security issue the United States should focus on next, she might say the moon. In fact, that’s exactly what she recently told a student at an event hosted by…