For the love of lizards: ASU researcher studies evolution of these 'fascinating' reptiles

Associate Professor Anthony Barley spent two weeks this summer studying whiptail lizards in Mexico. Photo by Anthony Barley

Editor's note: This is the fourth in a five-part series about ASU faculty conducting summer research abroad. Read about carbon collection in the Namib Desert; a pilot program to address HIV care in Uganda; and the world's tallest palm trees in Columbia.

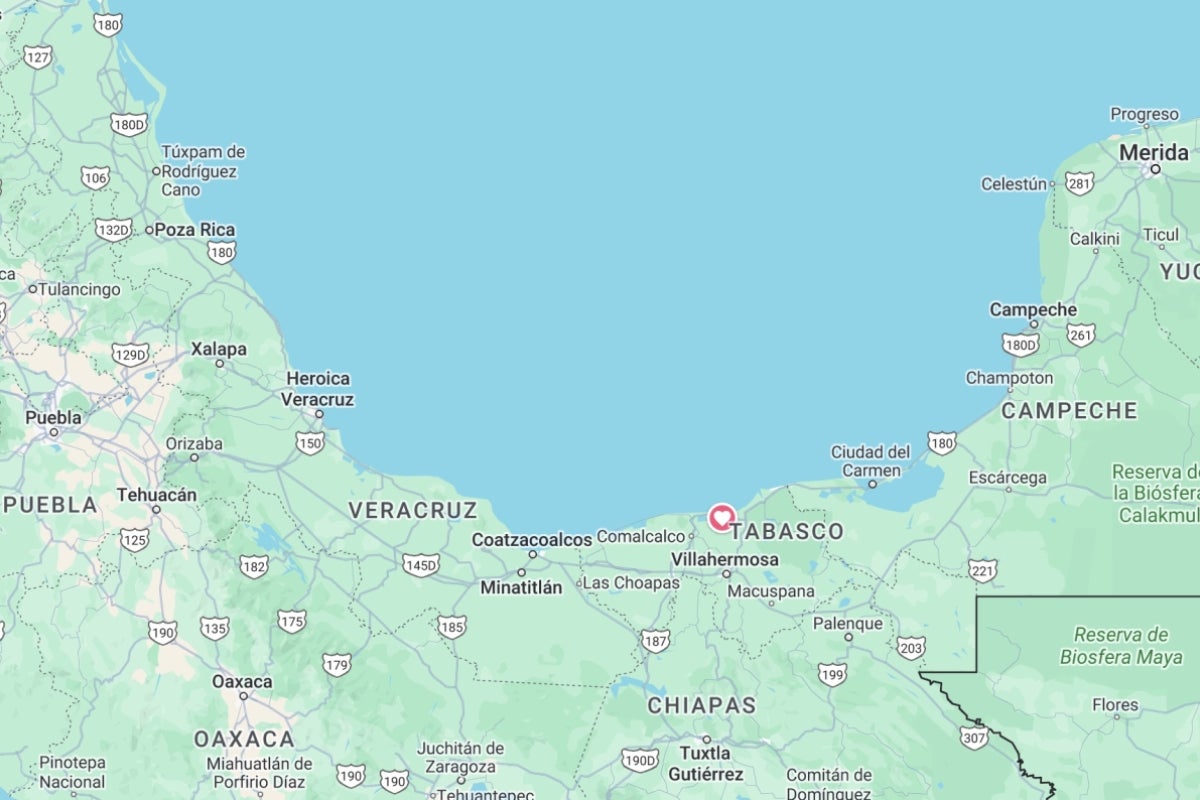

Anthony Barley spent nearly two weeks lassoing whiptail lizards in Mexico this summer.

Armed with an extendable fishing pole with a noose made of fishing wire, the Arizona State University teacher traveled through lowlands and mountains, dry forests and rainforests researching his favorite reptile.

“It’s very challenging because these lizards are very fast,” said Barley, who has perfected the practice after capturing nearly 100 of these scaly creatures during the past 15 years.

Barley’s time commitment to this creature can be explained with one word.

They are “fascinating,” says the assistant professor in ASU’s School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences in the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences

Fascinating indeed. Lizards can swim, sprint, climb — and some can run on just two legs. One species is even called the “Jesus lizard” for its ability to walk on water.

Barley is most interested in the interbreeding among lizards and their almost inconceivable capacity to reproduce without the aid of a male. His goal is to understand the evolutionary processes that cause different species to change over time.

Question: What is it about lizards that you love so much?

Answer: The thing I find most fascinating about them is the diversity of the species that exist on earth. There are more than 7,000 species, and they show incredible diversity in how they look (their morphology), the habitats they live in and how they make a living (their ecology).

I find the many ways in which different species have adapted to life on earth incredibly fascinating.

Q: You have a special interest in the whiptail lizard? Why?

A: These are incredibly interesting lizards. For one, they are really neat-looking reptiles that live in a huge variety of habitats and are extremely active.

I am most interested in them for a couple reasons — one being that they are the group of vertebrates that includes the largest number of unisexual species that consist only of females that can clone themselves. I am studying how these species came to be and what the consequences of reproducing without sex are for them.

They are also really interesting because many of the species that do have sex hybridize with other species that look very different from each other in the way they interbreed and produce offspring.

Q: How do they reproduce without a partner?

A: These female lizards lay eggs that can spontaneously develop without needing to be fertilized. This is because they have a special mechanism of meiosis that allows them to produce eggs that are diploid instead of haploid — like eggs of most species. They are also clones, having the exact copies of the mother's DNA.

Q: The process of your research begins with you catching lizards and preserving tissue samples. What does catching lizards entail?

A: It is tough because these lizards are very wary of people and usually seek refuge in dense vegetation.

So, we work in teams to surround the lizards then slip a lasso around their neck to capture them. You have to be very quick; it has taken me a very long time to get effective at this, but still the success rate is very low.

Q: How does hybridization impact the evolution of a species?

A: In many different ways! In some cases, exchanging genes can be problematic because it creates genomic combinations that are not well suited to their environment — for example, offspring that have combinations of alleles that do not work well together. Sometimes, it can be beneficial, though, by helping species adapt to their environments.

A fascinating example of this comes from humans. Some human populations that lived at high elevations in the Himalayan mountains have an allele that helped them adapt to living at high elevations. And it turns out that allele actually originally evolved in Neanderthals and was transferred into the human population through historical inbreeding — hybridization between humans and Neanderthals.

Hybridization can also lead to the evolution of new species. One example of this is unisexual species: Almost all the unisexual species of vertebrates were formed by hybridization — when two different sexual species produced a hybrid offspring that could reproduce asexually, which results in the instantaneous formation of a new species.

Q: Why are unisexual species significant?

A: Well, it is remarkable that they manage to persist without having sex, since we generally think of the benefits of sexual reproduction (genetic recombination) as foundational to species adapting to their environments.

This is an important aspect of the natural biological diversity that exists on earth. So in some ways, it’s just understanding the fundamental mechanisms that allow life to diversify on earth and are an important part of the existence of all species, including humans.

Q: What is the application of your research?

A: One application is the conservation of species. By studying how many species exist on Earth, society can plan to protect and conserve them for future generations. But, also, reproduction is one of the defining and most important characteristics of life on Earth. While understanding the variation in how species do this is important in its own right, it also could have applications to medicine and agriculture, since it involves advancing understanding of developmental processes that are fundamental to all species.

More Science and technology

ASU students win big at homeland security design challenge

By Cynthia GerberArizona State University students took home five prizes — including two first-place victories — from this year’s Designing Actionable Solutions for a Secure Homeland student design…

Swarm science: Oral bacteria move in waves to spread and survive

Swarming behaviors appear everywhere in nature — from schools of fish darting in synchrony to locusts sweeping across landscapes in coordinated waves. On winter evenings, just before dusk, hundreds…

Stuck at the airport and we love it #not

Airports don’t bring out the best in people.Ten years ago, Ashwin Rajadesingan was traveling and had that thought. Today, he is an assistant professor at the University of Texas at Austin, but back…