ASU archaeologist charts new course for history of the Wari Empire

Wari settlement at Cerro Baul, Peru, on top of the large mesa overlooking the ancient agricultural fields that fed the Wari state in southern Peru. Photo by Professor Ryan Williams

Decades of data give scientists new insight into the history of the rise and fall of South America’s earliest empire — the Wari, who lived in Peru from 670–1050 C.E.

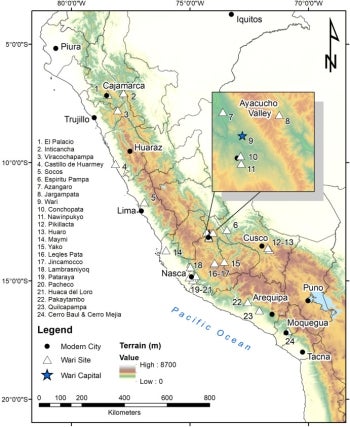

Arizona State University archaeologist Ryan Williams and colleagues analyzed 370 radiocarbon dates from across the Andes to chart the course of history of the Wari Empire — something that has not been done before.

“Radiocarbon dates can come from any organic matter — it does have to have been at one point a carbon-based life form,” said Williams, director and professor at ASU's School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

“Wood, seeds, textiles, bones related to the construction or use of archaeological sites or artifacts are all potential sources. Our data comes from all these source types.”

Some of the radiocarbon dates come from decades of past work; other dates come from excavations conducted by the authors that were not published until now. The team also used Bayesian statistical analysis techniques to pinpoint more precise dates.

“One of the key takeaways from our study is that the Wari Empire was not a monolithic or all-encompassing political entity,” said David A. Reid, co-author and visiting research assistant professor at the University of Illinois Chicago.

“Instead, through statistical modeling of associated radiocarbon dates, we see the fits and starts of an early expansive state, reorganization periods where formal political and religious institutions become widespread, and regional variability of Wari direct presence.”

To construct a timeline, the researchers focused on six large regions of the empire and analyzed when imperial influence in local communities started and ended. Williams and the team broke the six regions into sites, dated each site and used three classifications: Wari state installations, Wari affiliated sites and local sites without evidence of Wari engagement.

Wari leaders lived and ruled over Wari people at the state installation sites. The archaeologists determined this by looking at buildings and infrastructure, as well as artifacts. Affiliated sites had no infrastructure to indicate the Wari built state institutions in that space, explained Williams. Local sites were areas with some Wari influence, few Wari trade goods and no infrastructure affiliated with Wari construction.

The team was surprised to find that religious and political institutions preceded institutions that supported information technologies in the growth of the Wari Empire.

“We often think that the growth of large polities requires communication systems that tie them together,” Williams said. “The growth of the U.S. was very much tied to the establishment of the transcontinental railroad, the Pony Express and other means of rapid communication across long distances.”

“For the Wari, roads that runners could pass information along quickly were a key information movement technology. The quipu, or knotted rope records that encoded information in material form (like a tax record), were another. They both appear to be fairly late inventions for the Wari.”

The article “Wari across the Andes: Modeling the radiocarbon evidence” was published in Quaternary International.

More Local, national and global affairs

First-ever Taiwan Symposium at Thunderbird celebrates business, cultural connections

The investment by TSMC and other Taiwanese corporations in Arizona will reap dividends not only in thousands of new jobs but also in strengthened cultural connections and new methods of…

Study shows that trust drives successful market economies — but not in the way you may think

From fueling our cars to fulfilling daily coffee habits, the average U.S. cardholder makes 251 credit card transactions per year, according to Capital One.Each of these transactions are built…

Higher education key to US competitiveness, security

ASU President Michael Crow’s notion of universities as public service institutions — places that serve society in practical and meaningful ways to solve pressing issues of importance to the country…