Reclaiming a lost history

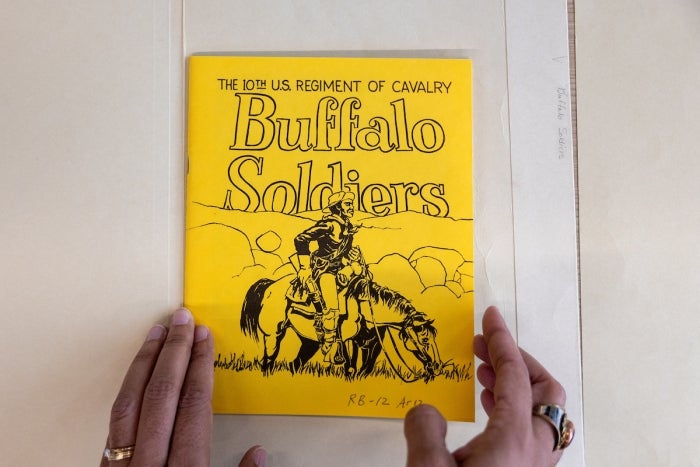

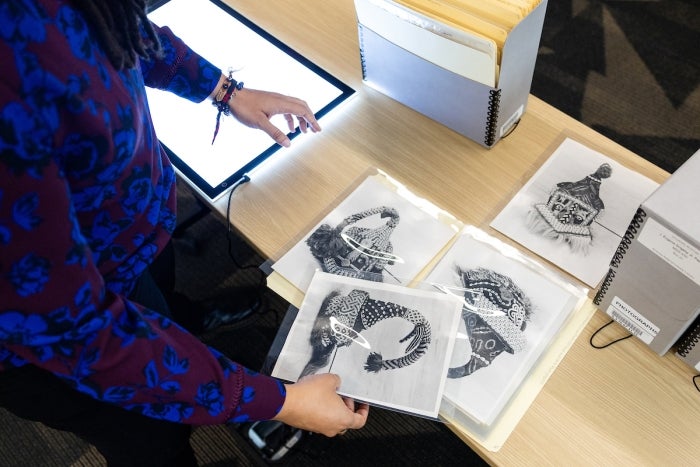

Jessica Salow, an assistant archivist with the ASU Library, reviews items from the J. Eugene Grigsby Jr. Papers. Grigsby was an influential Black artist, scholar and longtime ASU professor. The collection contains 44 boxes of material and is considered one of the gems of ASU's Black Collections. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU

Editor’s note: This is part of a monthly series spotlighting special collections from ASU Library’s archives throughout 2024.

Arizona’s Black and African American community has woefully been underrepresented in the telling of the state’s history.

However, a repository at Arizona State University that has been quietly taking shape aims to properly acknowledge the influence and rich history of Black and African American communities across the state.

This Black History Month, the ASU Library, which houses the repository, has put out the call for community members to contribute their stories, so their chronicle is not lost.

“Less than 2% of all archival collections in Arizona represent Black and African American communities, and that is an unfortunate statistic because we’ve been here before territorial times, during territorial times and after territorial times,” said Jessica Salow, assistant archivist of Black Collections at ASU Library.

Related story

ASU archivists hoping to learn more about early African American students

“The work we do is vital, which is why we are institutionally trying to create repositories but also trying to encourage communities to be involved in the preservation of their own stories and memories.”

ASU’s Black Collections is a relatively new archive but is gaining steam.

It started in 2021 with a generous grant by ASU’s LIFT (Listen, Invest, Facilitate, Teach) Initiative. Salow said the grant helped fund her position within the Community-Driven Archives Initiative, which is reimagining and transforming academic libraries and archives.

Black Collections is focused on creating a robust community collection dedicated to documenting the lived experiences of Black people living and thriving in Arizona.

That’s why a big part of Salow’s job will be community engagement, and “being available to others.”

“It takes years, even decades, for a collection to come to fruition depending on institutional support and community engagement,” said Salow, a history major who graduated from ASU in 2011. “We absolutely need engagement from the community for this collection to be of substance, of understanding, and tell the stories that need to be told. Legacy building is super important, and that’s what this work is.”

Salow said her goal is to spark archival Black and African American collections throughout Arizona, and at ASU.

This can be achieved through a variety of ways, including photos, ephemera, oral histories and papers.

Salow has attended several community events to get the word out, including meetings with the Maricopa County chapter of the NAACP, ASU alumni gatherings, and partnering with the Arizona Historical Society, and Black Family Genealogy and History Society, for the annual Juneteenth Celebration.

She has also hosted several workshops on archival theory and collection with local high schools and ASU professors and students.

“We talk to them as professionally trained archivists on how to start or preserve their history,” Salow said. “Through those workshops, I’ve had individuals come up to me and say they have documents and then we start a conversation. That’s how word of mouth has developed about what I’m doing and what I am hoping to accomplish.”

One family who didn’t need convincing were the heirs of J. Eugene Grigsby Jr., an influential Black artist, scholar and longtime ASU professor.

“It’s certainly an honor for us and our father to participate in this project because my dad was very committed to his work and to the students at ASU,” said Grigsby's son Marshall Grigsby, who helped prepare the J. Eugene Grigsby Jr. Papers — one of the gems of the Black Collections.

It’s also the first in the Black Collections to be arranged, described and made available for research online via Arizona Archives.

“My father gave of himself to the university, the community and anyone who was interested in art. I see this collection as an extension of his pioneering leadership and life’s work,” Marshall said.

A native of North Carolina and a painter since the age of 12, Grigsby earned his bachelor’s degree in art at Morehouse College, a master's degree from Ohio State University, and a PhD from New York University.

He headed west to Arizona after serving in World War II, where he was offered a teaching position at the all-Black Carver High School in 1946. When Carver closed, Grigsby taught at Phoenix Union High School for a dozen years before coming to ASU in 1966.

At ASU, Grigsby taught art education and served as the adviser to Give a Damn Art Teachers, a student organization formed in the late 1960s to give students opportunities to interact with learners from a variety of ethnic and socioeconomic backgrounds.

He also had an extensive and diverse art career, which included painting, printmaking, teaching, consulting and lecturing.

The Grigsby Papers measures approximately 22 linear feet and contains 44 boxes of material, roughly organized into three major categories: Grigsby’s research activity focusing on African art and masks; his teaching career at Phoenix Union High School, and at ASU, where he was one of the first Black faculty members in the College of Fine Arts; and numerous images of Grigsby’s wife and children, as well as more distant relatives.

Marshall and his father’s two primary caregivers, Mark and Martina Herring, began arranging the collection after Grigsby's death in 2013.

Marshall said he took several trips from his Washington D.C.-area home to Tempe, over the course of several years, to organize and prepare the collection for the public. He said he learned more about his father as a result.

“My dad was a Renaissance man and was engaged in all kinds of things,” said Marshall, who took an art appraisal class at George Washington University to place a value on his father’s artwork.

“I discovered he was a playwright at times. He even wrote music. He was engaged in a lot of things. Being close to it growing up, you don’t always see everything going on. Going through his collection made me realize he had a tremendous amount of imagination, energy and creativity.”

Lincoln Ragsdale Jr. is currently going through that process now. He has been actively working on his papers from his father, Lincoln Ragsdale Sr., for the past few years.

Like J. Eugene Grigsby Jr., Lincoln Ragsdale Sr. was also Renaissance man.

Born in 1926, Ragsdale Sr. was a Tuskegee Airman who served with distinction in World War II. His service in the military motivated him to become a civil rights leader in Arizona after a stint at Luke Air Force Base as part of an integration experiment.

After the war, Ragsdale Sr. became the second Black funeral homeowner in Arizona. He also earned a bachelor’s degree in economics at ASU and later a Doctor of Philosophy from Union Graduate School in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Ragsdale Sr. had holdings in a variety of industries, including insurance and real estate, with a focus on helping to end racial discrimination against Black people.

He and his wife, Eleanor, a schoolteacher, were members of the NAACP Maricopa County chapter and the Phoenix Urban League, and founded the Greater Phoenix Council for Civic Unity. As a couple, they organized marches and peaceful protests to create more jobs and job advancement for Black people and African Americans in the Phoenix area.

Ragsdale Sr. was the vice president of the NAACP Maricopa County chapter when they invited Martin Luther King Jr. to ASU in June 1964, a month before the landmark Civil Rights Act was signed into law by President Lyndon Baines Johnson. A reel-to-reel recording of that historic visit is currently available on ASU Library’s PRISM website, the digital repository of ASU Library’s archival holdings.

“I was flattered and honored when ASU asked me to submit my father’s papers, pictures and his Tuskegee Airmen uniform,” Ragsdale Jr. said.

Beyond Black History Month

Noteworthy anniversaries provide additional opportunities to learn about Black history

Ragsdale Sr. died in 1995 at the age of 68, and Lincoln said reviewing the donated items to the collection made him reflect on the sacrifices his parents and family made when attempting to integrate into the Valley.

“This process has brought back many wonderful memories, but also some negative memories, too,” said Ragsdale Jr., who is a successful Phoenix-area businessman with several real estate holdings.

“There were many casualties in the civil rights struggle. One of the casualties are the children of civil rights leaders,” he said. “Being the first African American children to integrate into schools and neighborhoods was a challenging and uncomfortable experience."

Ragsdale Jr. said he hopes the collection will serve two purposes: keeping his parents’ legacy alive and inspiring future activists.

“I’m hoping future generations and our community would feel uplifted and inspired to keep fighting for justice,” he said. “Everyone should have an equal opportunity to be successful and fair treatment no matter what their race or gender.”

Salow said the Ragsdale Family Papers should be ready for the public to make an appointment and view in the Hayden Library’s Wurzburger Reading Room after an announcement and celebration later this year.

Another collection currently being developed from the ground up will feature the life and work of Mark Ellis Sunkett, a beloved professor in the ASU School of Music who died in 2014.

Sunkett was an ethnomusicologist, and his research often took him to Senegal, West Africa, resulting in the formation of a Phoenix-based West African drum and dance troupe.

“Mark built this wonderful community of musicians and dancers at ASU that is sorely missed today,” said Sonja D. Branch, a dance accompanist senior in ASU’s School of Music, Dance and Theatre and a former research assistant for Sunkett. “He had this vibe about him that when he walked into a room, people would settle down and listen because they were so interested in what he had to share.”

Sunkett was a graduate of the Curtis Institute of Music and Temple University, both in Philadelphia, and held a PhD in ethnomusicology from the University of Pittsburgh. He performed with the Philadelphia Orchestra, was a member of "The President's Own" United States Marine Band and was principal tympanist with the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra.

He started teaching at ASU in fall 1976, and was one of a handful of Black professors at the university at the time.

Branch said in addition to his teaching duties and community work, Sunkett created a popular percussion jazz ensemble at ASU, which drew hundreds of people to its concerts over the years.

“These were big community events, and the ensemble had a very large following,” said Branch, who was the ensemble’s associate director. “If we had our concerts outside, people would come and bring their picnic blankets and watch our soundcheck, then hang out for the evening. If we were inside, audience members would stand up and dance. It was so much fun.”

Branch is reliving those days as she compiles photos, printed programs, audio recordings, videos of concerts, newspaper articles, presentations on PBS and recorded conferences on Sunkett’s research. She said the research she is doing is bringing Sunkett back, ensuring his memory is not lost.

“Mark is missed by many, and we’re almost 10 years from the time he passed,” Branch said. “He had such a transformative effect on so many people over the decades. It just seems like his life and legacy should not be forgotten.”

“We are not just documenting high-profile or ‘the important people,’” Salow said. “In order for this to be a true community-driven archival collection that documents all aspects of Black and African American history here in Arizona, everyday people also deserve to be reflected in this collection.

"We need those stories to tell, too.”

Monthly series spotlighting ASU Library’s special collections

- January: Expanded Theatre for Youth and Community Collection remains a repository for emerging artists and educators

- February: Black Collections aims to document the lives of an underrepresented Arizona community

- March: Voices from Latin America can be found in dynamic research collection

- April: Thunderbird archives: These walls do talk

- May: Collection preserves legacy of modern architects, buildings in the Southwest

- June: LGBTQ+ Studies Collection a repository rich in legacy

- July: Pop-up book collection is deceptively simple fun

- August: A (re)source of Sun Devil pride

- September: Chicano/a Research Collection filled with action, education and activism

- October: ASU collections offer Indigenous perspective through traditional storytelling, innovative methodology

- November: University Archives chronicles more than 140 years of Sun Devil history

More Arts, humanities and education

Veteran fast-tracks degrees through ASU, Uber partnership

Christopher Bordas is proof that with hard work and determination, anything is possible.At 45, the South Florida resident is graduating with his bachelor’s degree in public service and public…

A humanities link from Harvard to ASU

Jeffrey Wilson didn’t specifically seek out Arizona State University professors when it came to filling out the advisory board for his new journal Public Humanities.“It just turns out that the type…

The Design School wins award for impactful design education

Luis Angarita, program head for The Design School’s industrial design program, attended the inaugural Don Norman Design Summit in San Diego to accept the Don Norman Design Award, which honors…