Editor's note: This is the first in a series of Q&As highlighting Arizona State University researchers working around the world this summer. Read about tool excavation in Africa, motorbike research in Vietnam and conserving jaguars in Costa Rica.

Brenda Baker flew into Cyprus in early June. The divided island is located southwest of Turkey.

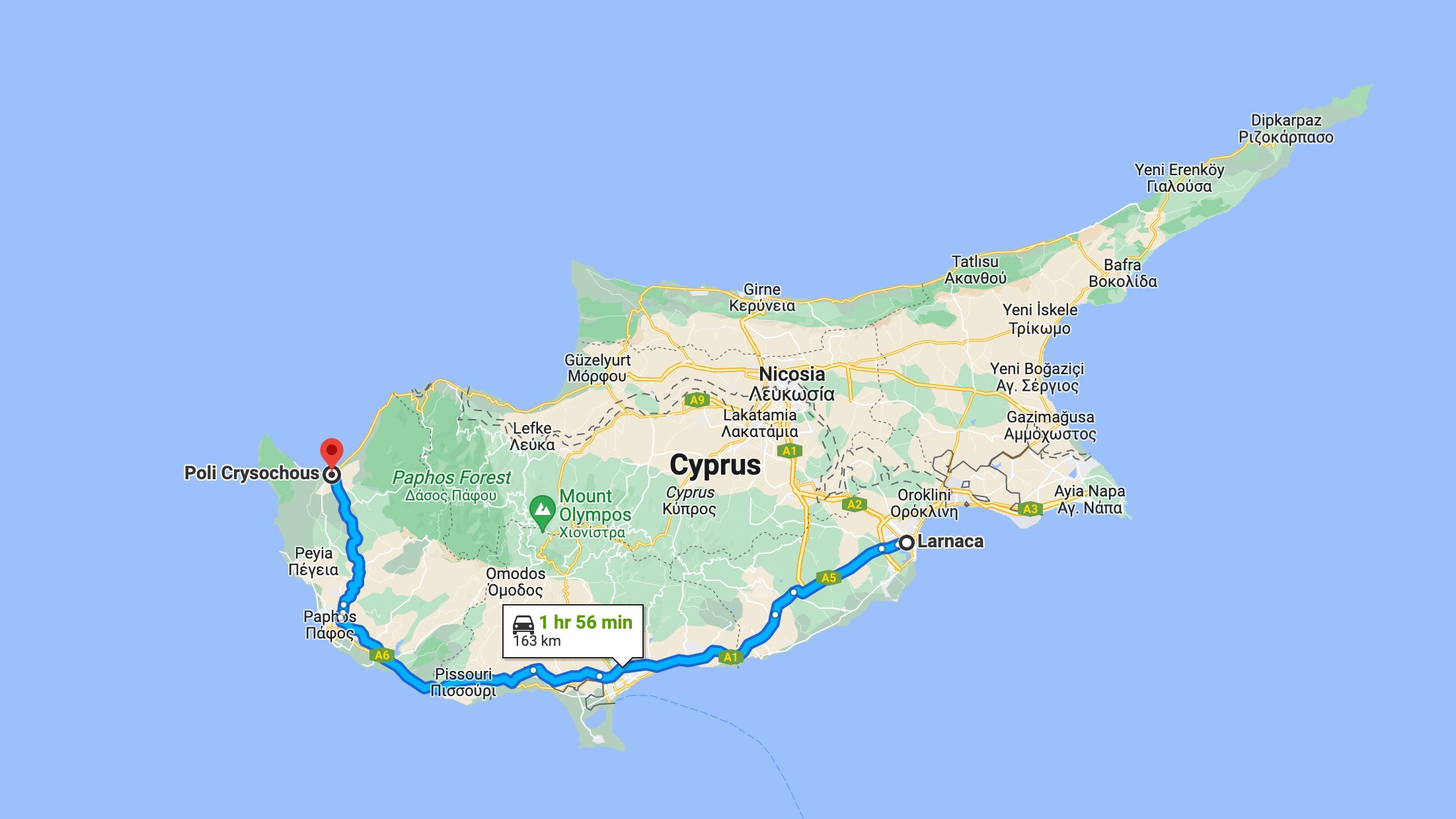

After securing a rental car, the ASU bioarcheologist followed the signs (written in both Greek and English) for more than 100 miles along the southern coast of the island, and then north from Paphos, on a winding, rural road to Polis. This small town rises on a bluff from the coast of the Mediterranean Sea, which Baker says varies in color from turquoise to cobalt blue.

It is here that Baker, an associate professor in the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, has been returning to since 2005 to conduct burial excavations.

Baker's route from the Larnaca International Airport to the excavation site in Polis, or Poli Crysochous, Cyprus. Image courtesy Google maps

The trip not only takes her a long way from her home in Chandler, Arizona, but her research takes her back hundreds of years — to the early sixth century when two stunning, sun-soaked basilicas were built on a bluff overlooking the bay and used for burials on and off until the 1500s.

The area continues to be the focus of her work as part of the Princeton University Cyprus Expedition. The goal of the project is to examine Hellenistic and Roman layers of the town that were discovered, as well as the late antique-to-medieval basilicas. Baker is the project’s bioarchaeologist and is in charge of studying the skeletons of people buried in and around the two churches some 500 to 1,700 years ago.

Her research has a two-fold purpose. It gives her a greater understanding of the history of Cyprus and the lives of the people who once lived there, and provides rich experiences to share with her students at ASU.

This year, Katelyn Bolhofner, a former graduate student who worked on the project more than 10 years ago, joined Baker in Cyprus. Bolhofner is now an assistant professor of forensic anthropology at ASU’s School of Mathematical and Natural Sciences.

ASU News checked in with Baker in Polis last week to hear about her summer research of uncovered skeletons in Cyprus.

ASU researcher Brenda Baker has been working at this excavation site in Polis, Cyprus, for many years. The excavations are near two basilicas. Baker is studying the skeletons of people buried in and around the churches 500 to 1,700 years ago. Photo by Katelyn Bolhofner

Note: Answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Question: Your typical work day starts at 8 a.m., with a tray of bones to study. What are skeletal bones from 1,700 years ago like?

Answer: Most skeletons are in a fair to poor state of preservation in the lab. The skeletons look complete when first exposed, but they have had all the organic components, such as collagen, leach out of them, so they are very brittle and crumbly. The many tiny roots that go through the bones also break them up, so we have a lot of fragments to work with rather than complete bones. It’s a giant puzzle to put back together.

Q: What is it like to spend so much time with skeletons?

A: It can be both frustrating, given the way the burials were excavated prior to my participation and preservation issues, and it can be rewarding, (especially when) relating to current residents about these ancient people, who were not so different from them. It can be exciting at times, as it was when finding evidence of leprosy in a young adult female.

Q: That was one of your most important discoveries. Why?

A: Her skeleton was the first archaeological example from Cyprus. Her burial within the entry hall of the church shows she was not ostracized by the community or barred from burial in sanctified ground.

The separation of people suffering from leprosy on Cyprus did not occur until Ottoman colonization, and they were further subjected to separate leper houses and stigmatization with British colonialism. So it is quite important to recognize that this female who died in her 20s participated in regular activities like sewing until she was no longer able to do so.

Baker works in her lab in Cyprus. Photo by Katelyn Bolhofner

Q: What have you been working on this week?

A: The last couple of days, I’ve been documenting the skeletal pathology in a man I excavated from a cistA cist is a small stone-built coffin-like box or ossuary used to hold the bodies of the dead. Source: Wikipedia tomb outside of the basilica back in 2005. His tomb was constructed of ashlar (limestone) blocks and covered with limestone slabs.

Many people were buried in simple pits dug into the ground, some with coffins evidenced by remnants of nails and some without coffins. The latter sometimes had stones placed on either side of the head to keep it in position. Most people were common folk, though some of the earlier burials within the main areas of each basilica were clergy or wealthier people.

Q: What else have you learned about the culture through your work?

A: The people in this area performed a lot of manual agricultural work, suffered mostly clavicle (collarbone and shoulder injuries) and rib fractures. They probably fished and, based on grooves in their teeth, did regular tasks like sewing and weaving.

The skeletons have revealed evidence of a division of labor through the different proportions of females versus males with grooves or notches on their teeth and in patterns of trauma.

While more adult males had trauma, it’s all accidental. In adult females, some is probably accidental but other injuries were certainly intentionally inflicted as indicated by cranial depression fractures and a “parry fracture” of a forearm bone that happens when someone is warding off a blow to the face.

Q: Sometimes excavations unearth extraordinary discoveries, but smaller observations are equally significant. Can you explain?

A: Yes. I’ve been documenting notches and grooves on incisor teeth that show they were being used as tools — mainly doing things like snapping thread along the side of a tooth. An adult female buried around 1,000 A.D. in the cemetery, excavated in 2005, was the first, we noted, to have grooves on her teeth. She had other skeletal alterations that support the contention that she was a seamstress.

Since then, I’ve documented grooves and notches on teeth of many other individuals, both male and female, though females predominate.

One of the most rewarding aspects of the discoveries here has been the discussions I’ve had with women who do local crafts — weaving, lacemaking, embroidery. When I told one shop owner in Polis about the teeth of our seamstress, with the deep grooves on the side of her top second incisor teeth, she exclaimed that she does the same thing and her dentist keeps telling her to use scissors instead of her teeth or she will break them off!

A Cypriot archaeologist who heard a presentation I gave told me that his mother does that, and it made this medieval woman come alive.

Top photo: Brenda Baker, an associate professor in ASU's School of Human Evolution and Social Change, spends time in a lab in Polis, Cyprus. Baker begins her work day by retrieving trays of bones from storage. The lab provides good light and a lot of table space to analyze the bones. Baker takes an inventory of what bones are present or absent and then determines the sex, dental wear and more. Photo by Katelyn Bolhofner

More Arts, humanities and education

Different ways of thinking, different ways of thriving: How ASU is supporting students with autism

According to the CDC, over 5.4 million adults in the U.S. are living with autism spectrum disorder, a condition that affects how individuals interact with others, learn and process information.…

Forever sewn in history

The historical significance of Black influence on fashion spans centuries. From the prints and styles of Africa to various American political climates, Black fashion has sealed its impact on the…

The Poitier Film School hosts Emmy-winning ‘Shōgun’ costume designer Carlos Rosario in LA

The Emmy and Golden Globe award-winning blockbuster FX series “Shōgun” doesn’t just have audiences in its thrall, but the creators who brought it to life, as well.“When the show came out, it just…