On a bright and early Saturday morning, a group of Arizona State University students gathered in a remote desert area, just west of Quartzite, Arizona.

Their reason for being there? To launch two large weather balloons that can carry a payload (mechanically and thermally stable containers) near the edge of space so the students can study how high altitudes affect a variety of objects — in this case, lettuce seeds.

The students are part of ASU chapter of ASCEND (Aerospace Scholarships to Challenge and Educate New Discoverers), an Arizona Space Grant program that engages undergraduate students across the state in the full “design-build-fly-operate-analyze” cycle of a space mission.

They were joined by volunteers from Arizona Near Space Research, an affiliate of ASCEND that helps coordinate balloon launches.

The students prepared two different seed packets for the payloads — one on the outside that will be exposed to high-altitude radiation and one on the inside that will just be exposed to the high altitude — to see how both the altitude and radiation exposure affects the seeds.

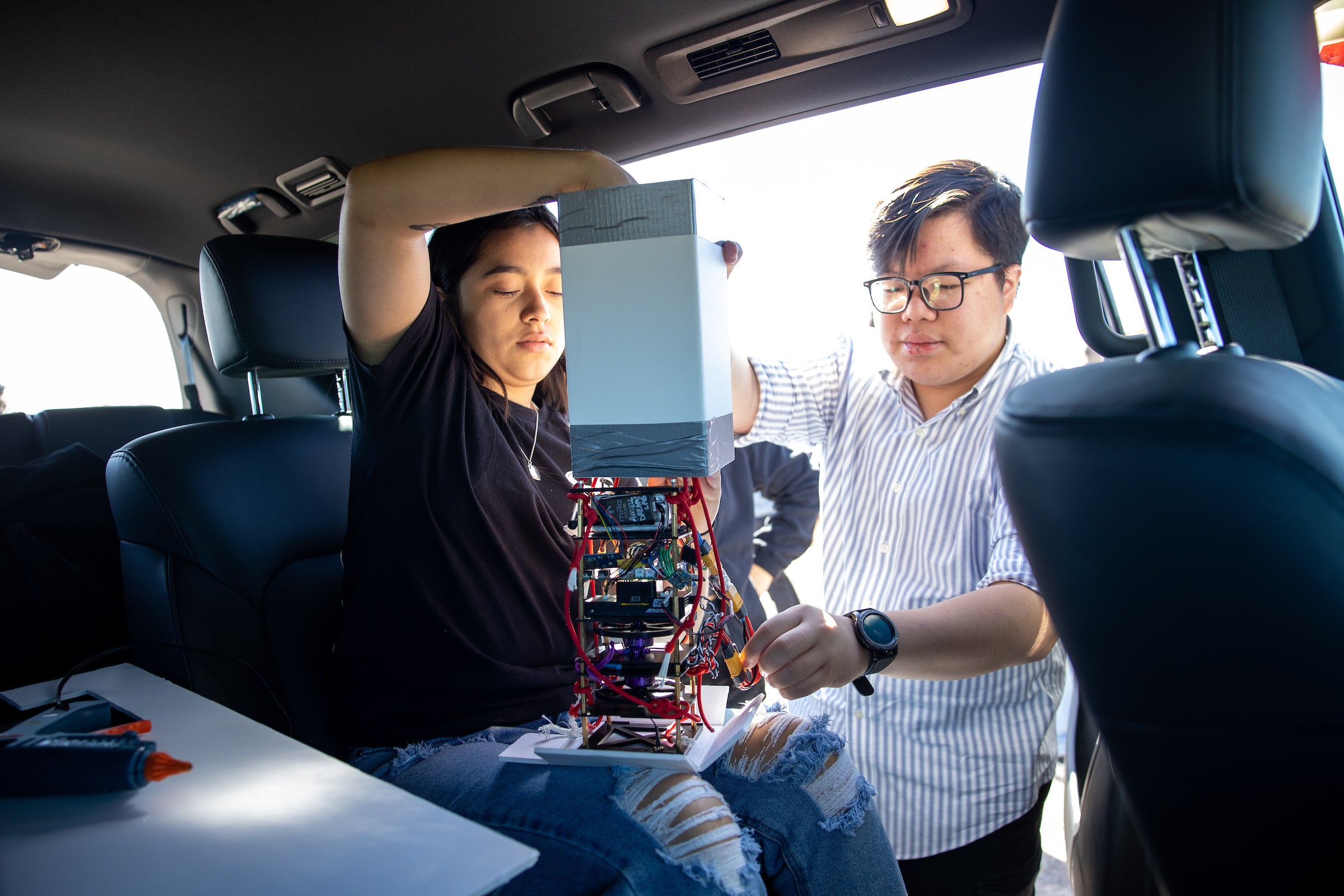

Aerospace engineering student Quang Huy Dinh (right) and mechanical engineering student Arlene Morales (left) help prep the payload prior to the balloon launch outside Quartzite, Arizona, on April 1.

Exploration systems design student Elizabeth Garayzar holds the weather balloon payload before the launch on April 1.

Professor Tom Sharp, in the School Of Earth and Space Exploration, and computer science undergraduate student Genevieve Cooper prep the payload for the weather balloon launch.

Cooper attaches lettuce seeds on the outside of the payload that will be exposed to radiation during the weather balloon experiment.

ASU students and volunteers from the Arizona Near Space Research group prep the helium weather balloon during the ASCEND launch outside of Quartzsite, Arizona, on April 1.

Students hold up the payload as it launches with the weather balloon on April 1.

Students watch as a payload and weather balloon take off. The balloons traveled upward of 100,000 feet before popping and parachuting back down to Earth in the Harcuvar Mountains Wilderness.

Photos by Deanna Dent/Arizona State University

More Science and technology

Ancient sea creatures offer fresh insights into cancer

Sponges are among the oldest animals on Earth, dating back at least 600 million years. Comprising thousands of species, some with lifespans of up to 10,000 years, they are a biological enigma.…

When is a tomato more than a tomato? Crow guides class to a wider view of technology

How is a tomato a type of technology?Arizona State University President Michael Crow stood in front of a classroom full of students, holding up a tomato.“This object does not exist in nature,” he…

Student exploring how AI can assist people with vision loss

Partial vision loss can make life challenging for more than 6 million Americans. People with visual disabilities that can’t be remedied with glasses or contacts can sometimes struggle to safely…