USDA-sponsored initiatives take on food safety concerns

Roughly one in six Americans (or 48 million people) are sickened every year by food-borne ailments, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The effects of these illnesses range from acutely unpleasant to lethal, and the problem may be getting worse, as our food supply becomes more global, with an increasing number of antibiotic-resistant pathogens.

Scientists at the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University are working to better diagnose and prevent two of the most pervasive food-borne microbes, relying on a pair of new USDA grants aimed at aggressively combating food-related illness.

Assistant research professor Melha Mellata and ASU Regents’ professor Charles Arntzen, both of the Biodesign Institute’s Center for Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology, will pursue different disease culprits. Mellata’s focus is on a harmful strain of the bacterial invader E. coli, while Arntzen’s research targets the stomach flu.

Chicken or egg

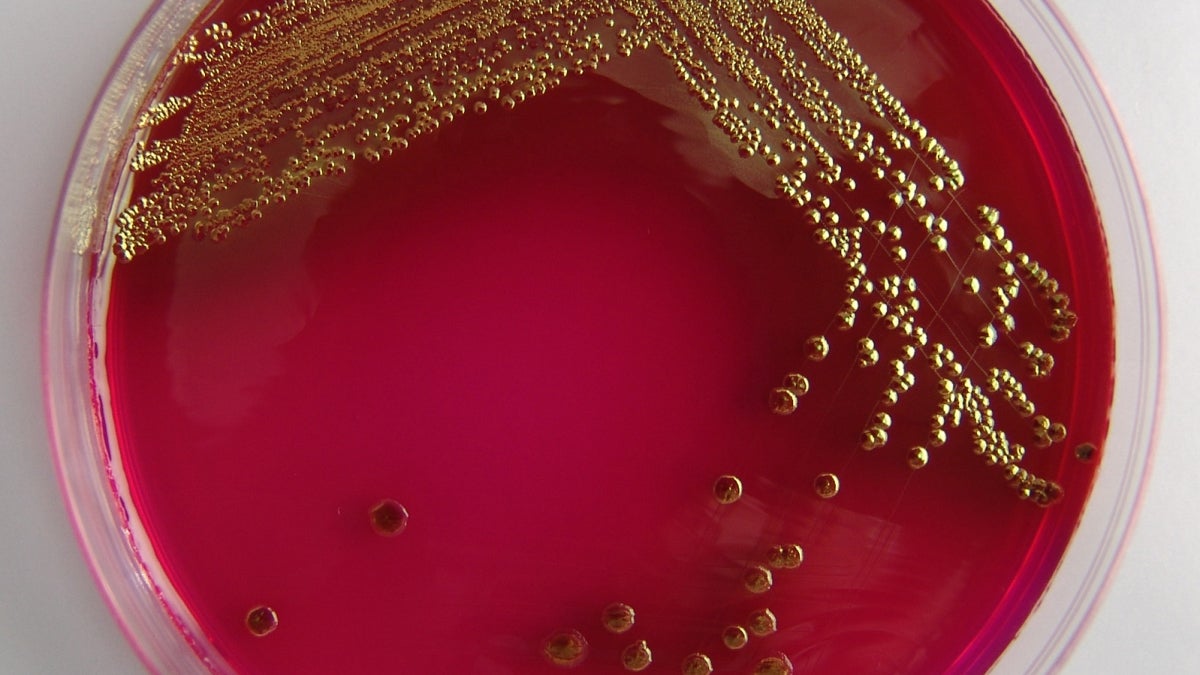

Mellata’s 5-year, $1.5 million USDA grant will investigate poultry products as a source of human extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC), a microbe that escapes the intestine to infect other tissues of the body, or the bloodstream.

Mellata emphasizes that this pathogen is of increasing concern for humans. In the U.S., millions of people contract ExPEC infections every year, resulting in 40,000 deaths. Extraintestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) can lead to an severe and sometimes fatal bloodstream infection known as sepsis. Elderly patients and those with compromised immune systems are particularly vulnerable to ExPEC, which can also produce urinary tract infections and newborn meningitis.

According to Mellata, “in poultry products such as eggs and meat, ExPEC is often overlooked and perhaps even dismissed as a danger for food production. Recognizing and treating the food source of ExPEC would greatly enhance food safety and positively impact human health.”

Much of Mellata’s earlier research involved chickens, which are susceptible to avian pathogenic E. coli, or APEC—a subgroup of ExPEC. Bacterial outbreaks at chicken farms have caused major economic losses for the poultry industry and infected chicken products are a likely transmission route for bacteria to infect humans.

Biodesign’s new research into ExPEC has two goals: 1) assess the food-borne health risk to vulnerable human populations 2) develop a novel and economical strategy to reduce or eliminate the contamination risks.

Toward the second goal, Mellata’s team, with input from Roy Curtiss, director of the Center for Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology, will work to develop a suitable poultry vaccine to prevent the risk of infection at its source. The vaccine candidate is based on another food-borne disease culprit, salmonella, which the Curtiss group, through genetic engineering, has recast to create a suite of experimental vaccines against a range of human and animal pathogens. The project compliments an ongoing, two-year, $400,000 National Institutes of Health award to develop a human vaccine against ExPEC.

Going viral

By far the most widespread food-borne threats are not bacteria at all, but viruses. Of these, Norwalk-like viruses, or noroviruses (named for the first such outbreak of stomach flu in a school in Norwalk, Ohio in 1968), account for two-thirds of all food-borne illness cases, 33 percent of hospitalizations, and 7 percent of deaths.

Arntzen and colleague Chris Diehnelt will collaborate on a multi-institutional $25 million USDA led by North Carolina State University – the largest funding initiative ever directed specifically at food-borne illness. Arntzen notes that “some viruses can contaminate the food supply, and a viral family called noroviruses is the worst of these in terms of causing hospitalization and lost work. The extreme diarrhea and discomfort caused by noroviruses has caused closures of hospitals, schools, homes for the elderly, and also disrupted travel—especially on cruise liners.”

The ASU scientists will provide better methods for detection of noroviruses in food, water and environmental samples. “Our effort at ASU will be to devise novel detection technology,” Arntzen says. “This effort is led by Chris Diehnelt, Ph.D., of Biodesign’s Center for Innovations in Medicine. The goal is a very rapid system to sample the food supply and to be able to detect and remove contaminated products before they are consumed.”

In the current project, the team will focus on norovirus contamination in three major foods: shellfish, produce and ready-to-eat food. The team will evaluate a new technology, binding reagents called synbodies, that may be used to produce a rapid, low-cost diagnostic test for identifying noroviruses.

Both ASU research initiatives promise to make significant strides in limiting risks from ExPEC and norovirus, two of the most insidious food-borne pathogens.