ASU alum finds success in neuroscience

ASU alumnus Justin Wolter recently accepted a tenure-track faculty position in the Department of Medical Genetics at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Photo courtesy Justin Wolter

A long and winding road led Arizona State University alumnus Justin Wolter to a career that he is truly passionate about. In his own words, “You never really know where science and life are going to lead you.”

Wolter’s first job out of college made him miserable. When he was 28 years old, his wife, Melissa, a graduate of ASU’s Master of Architecture program, encouraged him to make the difficult decision to go back to school. With her and their young child in tow, Wolter joined ASU’s School of Life Sciences to pursue a PhD in molecular and cellular biology.

Wolter, who was older than most of the graduate students in his classes, was desperate to gain lab experience in a field that was completely new to him. Kenro Kusumi, who is now dean of natural sciences at The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, was one of those faculty who took a chance on Wolter.

“Justin had that spark of enthusiasm about biology that made us want to have him at ASU. I had the pleasure of collaborating with Justin later on a research project focused on regeneration, and his efforts were critical for that publication,” said Kusumi.

“After many months of harassing Kenro, saying, ‘Please let me work in your lab!’ he gave me the first shot that I needed to get me off the ground,” said Wolter.

That first shot was covering the weekend shift of keeping cells alive in tissue cultures — a time slot that other students were not eager to take on. But that work prepared Wolter for his next lab experience with Marco Mangone, whom Kusumi connected him with.

Mangone was a new faculty member at ASU in need of graduate students to pursue research on gene regulation in roundworms and human cells.

“What got me excited about Marco’s lab was thinking about how these genes are the same in worms and in humans, why they stayed the same during the long evolutionary journey between worms and humans, and how you can use one to understand the other,” he said.

While there, Wolter’s love and curiosity for science fueled his research endeavors.

“If I had to choose just one word to describe Justin, it would be ‘passionate,’” said Mangone.

“He is very excited about science and speaks about it constantly. During his five years in my lab, he routinely stopped by my office, outlining experiments and potential models that he conceived the day before, based either on a manuscript he read or on results produced by his last experiments.”

In recognition of his scientific achievements and promise of success, Wolter was awarded the Maher Alumni Scholarship, which supports graduate student work on cancer research. He received the scholarship four times in a row.

“As somebody that was raising a family through graduate school, it was really instrumental and crucial to have the Mahers’ support, from a financial standpoint, but also just the motivation that comes along with somebody saying that what you do is important.”

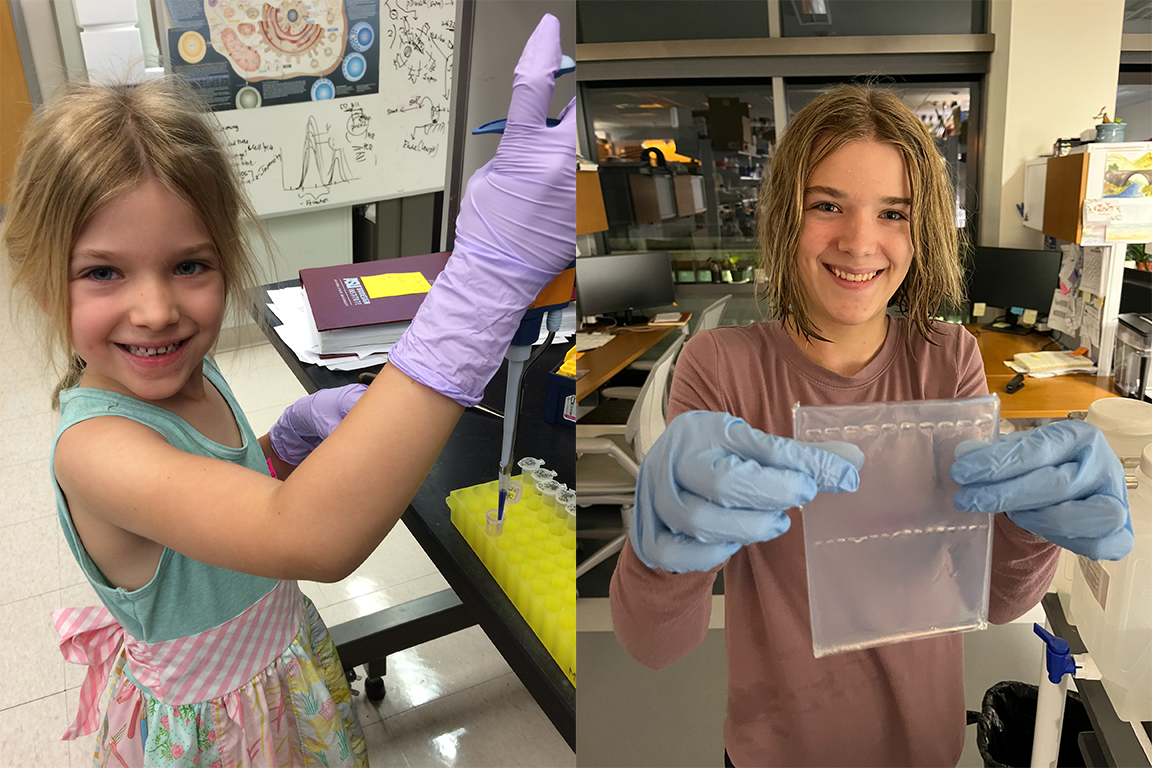

Then vs. now: Justin Wolter's daughter Adelyn helping in the lab. When Wolter was pursuing his PhD and working in Marco Mangone's lab, his daughter would often join him. Now she and her brother Jude still enjoy accompanying Wolter and experiencing research in a lab. Photos courtesy Justin Wolter

Several other faculty members helped Wolter succeed. Manfred Laubichler and Jane Maienschein instilled in him a love of evolution and the history of science. Jason Newbern, whom Wolter took a class from in his last semester at ASU, solidified his love for neuroscience and his desire to pursue his own neuroscience research.

Wolter received his PhD in 2016. Even as a nontraditional student raising a family while managing his studies, he was able to complete his PhD almost one semester early.

He then completed his postdoctoral research at the University of North Carolina, where he investigated how human genetic variation influences disease outcomes — work that intersected with his cancer research at ASU.

“I came to UNC to study neurodevelopment and how the brain develops, and it turns out that a lot of neurodevelopmental diseases have features in common with cancer,” he said.

“For example, a lot of kids with autism have macrocephaly, so enlarged brains, and several genes that are implicated in autism are also well-known tumor suppressors or oncogenes, which are mutated or hyperactivated in cancer.”

Wolter and his team at UNC found a way to take individual human cell lines and identify how genetically diverse cells respond differently to clinically relevant treatments.

Now, Wolter has accepted a tenure-track faculty position in the Department of Medical Genetics at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Together, his postdoctoral research on autism and graduate studies on cancer have motivated the research that he will pursue at his new lab at UW-Madison.

“I'm sticking with neuroscience but have chosen to focus on the brain overgrowth aspect of autism, and that was directly related to the support of the Maher family and them keeping me focused on cancer. So at the end of the day, these two parts of my training in graduate school and my postdoc have really come together in a unique way.”

Wolter also credits his family for helping him pursue his dream. “My family has been a huge part of the journey. I started graduate school with one daughter. I had two more kids in graduate school and I've had a fourth one during my postdoc,” he said.

“Far from slowing me down, I really feel they have helped me stay focused and motivated.”

“I have a picture of my daughter when she came in on a weekend to ‘help’ me in Marco’s lab. Now she needs bigger gloves, but her and her brother Jude still help me in the lab, and Adelyn wants to do a PhD. I’ve had a blast dragging my family on this crazy ride with me.”

Wolter, his wife and four kids look forward to settling in Wisconsin near family and where Wolter can continue to pursue the research that he loves.

He signed his acceptance letter for his latest role at UW-Madison using the same pen his ASU mentors gave him when he successfully defended his dissertation six years ago.

More Science and technology

Hack like you 'meme' it

What do pepperoni pizza, cat memes and an online dojo have in common?It turns out, these are all essential elements of a great…

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive —…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper…