Black history is not always taught in public schools throughout the country. But like any history, it is important to know and understand where we’ve been, reflect upon where we are today, and use the power of the past to impact, improve and determine the future.

In honor of Black History Month, ASU News asked five Arizona State University professors to help create a list of essential reads — books that they’ve read, books that they’ve taught, books that advance and enhance the understanding of Black history.

Here are their recommendations.

Andrew Barnes

“Invisible Man,” by Ralph Ellison

Recommended by Andrew Barnes, professor of history, School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies

First lines: I am an invisible man. No, I am not a spook like those who haunted Edgar Allan Poe; nor am I one of your Hollywood-movie ectoplasms. I am a man of substance, of flesh and bone, fiber and liquids — and I might even be said to possess a mind. I am invisible, understand because people refuse to see me. Like the bodiless heads you see sometimes in circus sideshows, it is as though I have been surrounded by mirrors of hard, distorted glass. When they approach me, they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imaginations — indeed everything and anything except me.

About the book: “Invisible Man” is considered an American classic. The book is a protest against racism and a sense of invisibility experienced by Black people. Written in prose poetry, it is a narrative about a young African American man who comes to New York City during the Harlem Renaissance and the challenges he endures.

Why is it an essential read? "I have taught it in the past as a Black intellectual commentary on African American political efforts over the first half of the 20th century. The book is arguably the greatest novel written by an African American, though obviously there are other contenders. Ellison takes the reader through Booker T. Washington's misplaced optimism, through the Jazz Age and an African American existentialism crisis, through Black nationalism, then Black communism to the determined stoicism collectively shared at the start of the civil rights movement."

Calvin J. Schermerhorn

“The Warmth of Other Suns,” by Isabel Wilkerson

Recommended by Calvin J. Schermerhorn, professor of history and African American history, School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies

First lines: The night clouds were closing in on the salt licks east of the oxbow lakes along the folds in the earth beyond the Yalobusha River. The cotton was at last cleared from the field. Ida Mae tried now to get the children ready and to gather the clothes and quilts and somehow keep her mind off the churning within her. She had sold off the turkeys and doled out in secret the old stools, the wash pots, the tin tub, the bed pallets. Her husband was settling with Mr. Edd over the worth of a year’s labor, and she did not know what would come of it. None of them had been on a train before — not unless you counted the clattering local from Bacon Switch to Okolona, where, “by the time you sit down, you there,” as Ida Mae put it. None of them had been out of Mississippi. Or Chickasaw County, for that matter.

About the book: Schermerhorn describes the book as an epic history of the Great Migration. It is the emigration of several million African Americans from the Jim Crow South to the north and west between World War I and about 1970. It is written from the perspective of several migrants out of hundreds whom Wilkerson interviewed. More than a migration story, this nonfiction charts the geographic itineraries and social realities of Black America in the 20th century. This migration changed the American landscape.

Why is it an essential read? "It is important because it gets inside a process most Americans don’t know well or have misunderstood. To those looking back at African American history since the Emancipation in 1865, it may seem like there was not a lot going on in the South until the civil rights era. But Wilkerson's historical storytelling captures the tense moments in which families rooted in place for generations must decide to accept ongoing racial violence or leave. And the tension builds through the book over how they slip the chains of Jim Crow and navigate urban landscapes that are distinctly unfriendly."

Neal Lester

“The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches,” by W.E.B. Du Bois

Recommended by Neal Lester, Foundation Professor of English, The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences and founding director of Project Humanities

First lines: Between me and the other world there is ever an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or I fought at Mechanicsville; or, Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

About the book: Written after the Civil War, it is a collection of 14 different essays that provide specific examples of racial injustice. According to Lester, the book is a work of American literature that is considered a cornerstone of African American history.

Why is it an essential read? "The book offers multiple ways to demonstrate and document the absolute fact that U.S. racism exists. Because race is a social construct, it is often challenging for those most impacted negatively by systemic racism to prove that they have been affected by it. In multiple chapters, Du Bois offers an array of cogent examples of how racism exists — everything from a personal autobiography to a fictional short story about the lives of two Johns — one white and one Black — to the anger of a Black minister who celebrates the death of his infant son because he will not have to experience racism as the father has. Du Bois’ treatise is a buffet of Black experiences — emotional, political, cultural, physical and spiritual — all wrapped up in the title itself that defies racist, demeaning and dehumanizing stereotypes and caricatures so popular at the turn of the century."

Monica Espaillat-Lizardo

“Discourse on Colonialism,” by Aimé Césaire

Recommended by Monica Espaillat-Lizardo, history instructor, School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies

First Lines: A civilization that proves incapable of solving the problems it creates is a decadent civilization. A civilization that chooses to close its eyes to its most crucial problems is a stricken civilization. A civilization that uses its principles for trickery and deceit is a dying civilization.

About the book: Written in prose poetry, the book highlights the hypocrisy of colonialism. The message of the book, often referred to as a manifesto, is that colonialism was not and had never been a benevolent movement whose goal was to improve the lives of the colonized; instead, colonists' motives were entirely self-centered, economic exploitation.

Why is it an essential read? "It is an essential read because it places Black history firmly at the center of, and makes it equivalent to, global history. 'Discourse on Colonialism' is a poetic treatise on the past, present and potential future lives of colonialism; it is a calling in, a challenge and a warning."

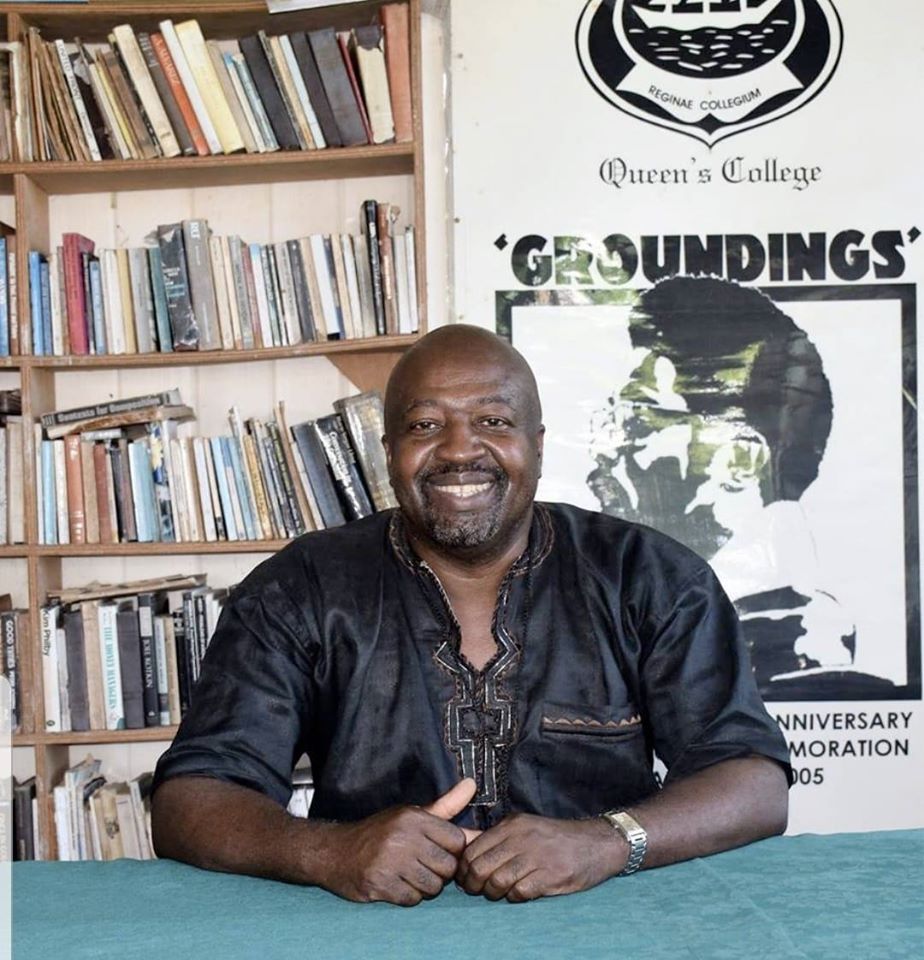

David Hinds

“How Europe Underdeveloped Africa,” by Walter Rodney

Recommended by David Hinds, associate professor of Caribbean and African diaspora studies, School of Social Transformation

First Lines: In contrast with the surging growth of the countries in the socialist camp and the development taking place, albeit much more slowly, in the majority of the capitalist countries, is the unquestionable fact that a large proportion of the so-called underdeveloped countries are in total stagnation, and that in some of them the rate of economic growth is lower than that of the population increase. These characteristics are not fortuitous: they correspond strictly to the nature of the capitalist system in full expansion, which transfers to the dependent countries, the most abusive and bareface forms of exploitation. It must be clearly understood that the only way to solve the questions now besetting mankind is to eliminate completely the exploitation of dependent countries by developed capitalist countries with all of the consequences that this implies.

About the book: The book has been called a meticulously researched analysis that describes how Africa was deliberately exploited and underdeveloped by European colonial regimes. One of his main contentions in the book is that Africa was developing Europe at the same rate that Europe was underdeveloping Africa.

Why is it an essential read? "When it was published in 1972, it changed the way African historiography was presented. Prior to that, scholars, well, mostly European scholars, approached Africa's underdevelopment from a Eurocentric standpoint. The book made the argument that African underdevelopment was not the result of internal dynamics in Africa, but it was linked to European development. It changed the way people began to see the history of Africa — that underdevelopment should not be seen in isolation from development in other countries."

Top photo by Karolina Grabowska via Pexels

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…