Researchers from Arizona State University and Zhejiang University in China, along with two theorists from the United Kingdom, have been able to demonstrate for the first time that large numbers of quantum bits, or qubits, can be tuned to interact with each other while maintaining coherence for an unprecedentedly long time, in a programmable, solid state superconducting processor.

Previously, this was only possible in Rydberg atom systems.

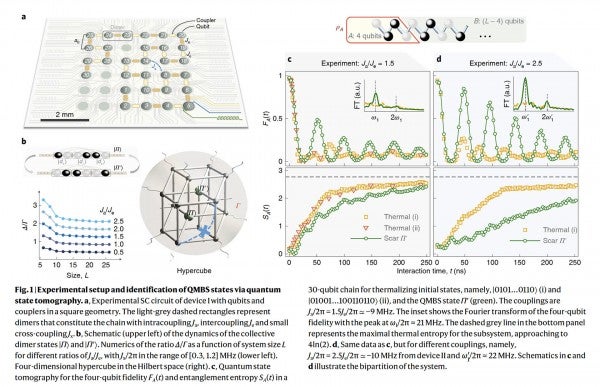

In a paper that was published on Thursday, Oct. 13, in Nature Physics, ASU Regents Professor Ying-Cheng Lai, his former ASU doctoral student Lei Ying and experimentalist Haohua Wang, both professors at Zhejiang University in China, have demonstrated a “first look” at the emergence of quantum many-body scarring (QMBS) states as a robust mechanism for maintaining coherence among interacting qubits. Such exotic quantum states offer the appealing possibility of realizing extensive multipartite entanglement for a variety of applications in quantum information science and technology to achieve high processing speed and low power consumption.

“QMBS states possess the intrinsic and generic capability of multipartite entanglement, making them extremely appealing to applications such as quantum sensing and metrology,” Ying said.

Classical, or binary, computing relies on transistors – which can represent only the “1” or the “0” at a single time. In quantum computing, qubits can represent both 0 and 1 simultaneously, which can exponentially accelerate computing processes.

“In quantum information science and technology, it is often necessary to assemble a large number of fundamental information-processing units – qubits – together,” Lai said. “For applications such as quantum computing, maintaining a high degree of coherence or quantum entanglement among the qubits is essential.

“However, the inevitable interactions among the qubits and environmental noise can ruin the coherence in a very short time — within about 10 nanoseconds. This is because many interacting qubits constitute a many-body system."

Experimental setup and identification of QMBS states via quantum state tomography. Photo courtesy Arizona State University, Zhejiang University

Key to the research is insight about delaying thermalization to maintain coherence, considered a critical research goal in quantum computing.

“From basic physics, we know that in a system of many interacting particles, for example, molecules in a closed volume, the process of thermalization will arise. The scrambling among many qubits will invariably result in quantum thermalization – the process described by the so-called Eigenstate Thermalization Hypothesis, which will destroy the coherence among the qubits,” Lai said.

According to Lai, the findings moving quantum computing forward will have applications in cryptology, secure communications and cybersecurity, among other technologies.

Collaborators from the School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Leeds, Leeds, U.K., include Jean-Yves Desaules and Zlatko Papić. Hekang Li fabricated the device at Zhejiang University. Other collaborators from Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, include Pengfei Zhang, Hang Dong, Jiachen Chen, Jinfeng Deng, Bobo Liu, Wenhui Ren, Yunyan Yao, Xu Zhang, Shibo Xu, Ke Wang, Feitong Jin, Xuhao Zhu and Chao Song. Additional contributors include Liangtian Zhao and Jie Hao from the Institute of Automation, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China, and Fangli Liu from QuEra Computing, Boston.

Top image courtesy Pixabay

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…