There in a flash: A weird star produced the fastest nova on record

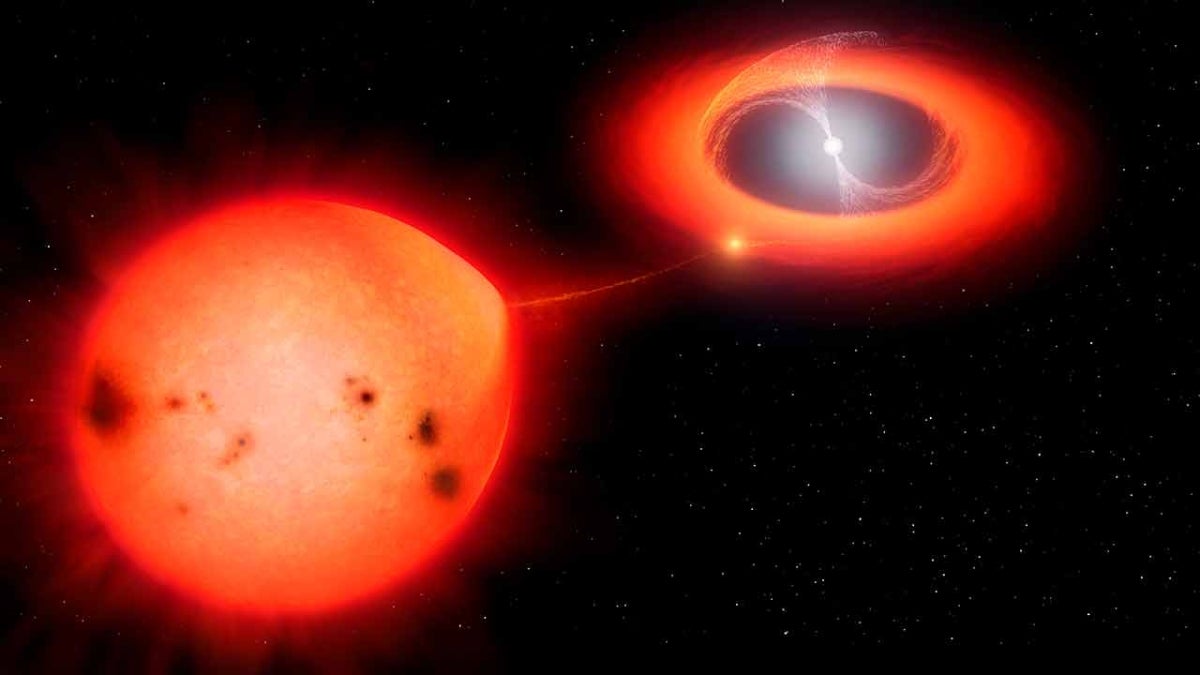

Illustration of an intermediate polar system, a type of two-star system that the research team thinks V1674 Hercules belongs to. A flow of gas from the large companion star impacts an accretion disk before flowing along magnetic field lines onto the white dwarf. Illustration by Mark Garlick

Astronomers are buzzing after observing the fastest nova ever recorded. The unusual event drew scientists’ attention to an even more unusual star. As they study it, they may find answers to not only the nova’s many baffling traits, but to larger questions about the chemistry of our solar system, the death of stars and the evolution of the universe.

The research team, led by Arizona State University Regents Professor Sumner Starrfield, Professor Charles Woodward from University of Minnesota and research scientist Mark Wagner from The Ohio State University, co-authored a report published today in the Research Notes of the American Astronomical Society.

A nova is a sudden explosion of bright light from a two-star system. Every nova is created by a white dwarf — the very dense leftover core of a star — and a nearby companion star. Over time, the white dwarf draws matter from its companion, which falls onto the white dwarf. The white dwarf heats this material, causing an uncontrolled reaction that releases a burst of energy. The explosion shoots the matter away at high speeds, which we observe as visible light.

The bright nova usually fades over a couple of weeks or longer. On June 12, 2021, the nova V1674 Hercules burst so bright that it was visible to the naked eye — but in just over one day, it was faint once more. It was like someone flicked a flashlight on and off.

Nova events at this level of speed are rare, making this nova a precious study subject.

“It was only about one day, and the previous fastest nova was one we studied back in 1991, V838 Herculis, which declined in about two or three days,” says Starrfield, an astrophysicist in ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

As the astronomy world watched V1674 Hercules, other researchers found that its speed wasn’t its only unusual trait. The light and energy it sends out is also pulsing like the sound of a reverberating bell.

Every 501 seconds, there’s a wobble that observers can see in both visible light waves and X-rays. A year after its explosion, the nova is still showing this wobble, and it seems it’s been going on for even longer. Starrfield and his colleagues have continued to study this quirk.

“The most unusual thing is that this oscillation was seen before the outburst, but it was also evident when the nova was some 10 magnitudes brighter,” says Wagner, who is also the head of science at the Large Binocular Telescope Observatory being used to observe the nova. “A mystery that people are trying to wrestle with is what’s driving this periodicity that you would see it over that range of brightness in the system.”

The team also noticed something strange as they monitored the matter ejected by the nova explosion — some kind of wind, which may be dependent on the positions of the white dwarf and its companion star, is shaping the flow of material into space surrounding the system.

Though the fastest nova is (literally) flashy, the reason it’s worth further study is that novae can tell us important information about our solar system and even the universe as a whole.

A white dwarf collects and alters matter, then seasons the surrounding space with new material during a nova explosion. It’s an important part of the cycle of matter in space. The materials ejected by novae will eventually form new stellar systems. Such events helped form our solar system as well, ensuring that Earth is more than a lump of carbon.

“We're always trying to figure out how the solar system formed, where the chemical elements in the solar system came from,” Starrfield says. “One of the things that we're going to learn from this nova is, for example, how much lithium was produced by this explosion. We're fairly sure now that a significant fraction of the lithium that we have on the Earth was produced by these kinds of explosions.”

Sometimes a white dwarf star doesn’t lose all of its collected matter during a nova explosion, so with each cycle, it gains mass. This would eventually make it unstable, and the white dwarf could generate a type 1a supernova, which is one of the brightest events in the universe. Each type 1a supernova reaches the same level of brightness, so they are known as standard candles.

“Standard candles are so bright that we can see them at great distances across the universe. By looking at how the brightness of light changes, we can ask questions about how the universe is accelerating or about the overall three-dimensional structure of the universe,” Woodward says. “This is one of the interesting reasons that we study some of these systems.”

Additionally, novae can tell us more about how stars in binary systems evolve to their death, a process that is not well understood. They also act as living laboratories where scientists can see nuclear physics in action and test theoretical concepts.

The nova took the astronomy world by surprise. It wasn’t on scientists’ radar until an amateur astronomer from Japan, Seidji Ueda, discovered and reported it.

Citizen scientists play an increasingly important role in the field of astronomy, as does modern technology. Even though it is now too faint for other types of telescopes to see, the team is still able to monitor the nova, thanks to the Large Binocular Telescope’s wide aperture and its observatory’s other equipment, including its pair of multi-object double spectrographs and exceptional PEPSI high resolution spectrograph.

They plan to investigate the cause of the outburst and the processes that led to it, the reason for its record-breaking decline, the forces behind the observed wind, and the cause of its pulsing brightness.

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would…