After months of testing, an ASU-designed and -built instrument to measure the surface temperature of a moon of Jupiter has arrived at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. There it will join eight other instruments and become an integral part of the agency's Europa Clipper spacecraft.

The instrument is the Europa Thermal Emission Imaging System (E-THEMIS) led by Regents Professor Philip Christensen of Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

The Europa Clipper is a robotic spacecraft sent to investigate Jupiter's ice-shrouded moon Europa. It is planned to launch on a SpaceX Falcon Heavy rocket in October 2024 and arrive at Jupiter in April 2030 after making flybys of Mars in 2025 and Earth in 2026. These planetary flybys use the masses of Mars and Earth to boost the spacecraft's velocity so it can reach the Jupiter system.

After entering orbit at Jupiter, the spacecraft will make about 50 flybys of Europa to investigate whether the moon could harbor conditions suitable for life.

Video by Steve Filmer/ASU

E-THEMIS is an infrared camera designed to map temperatures across Europa’s surface. Its images, taken in three heat-sensitive bands, will help scientists find clues about Europa’s geological activity, including regions where the moon's presumed ocean may lie near the surface. Although Europa is slightly smaller than Earth's moon, scientists think its ocean may hold twice the volume of Earth's oceans.

“Europa's surface is an extremely cold shell of ice, but the ocean below is liquid water," Christensen says. "E-THEMIS can see warmer regions, whether caused by impacts, convection or liquid water lying much closer to the surface than the ocean."

Even if many years have passed, he says, "The ice will still be warm. From these temperature images, E-THEMIS will give us an excellent opportunity to study the geologic activity of Europa."

Besides identifying any warm areas on Europa's surface, E-THEMIS images will also help scientists determine the physical state of the icy surface. As parts of Europa's landscape cool after local sunset, areas of solid ice will stay warmer longer, while those with a granular texture will lose heat more rapidly. By mapping the rates of cooling across the surface, scientists will better understand Europa’s small-scale properties. This technique might even help to identify sites for a possible future lander.

Measuring solar warmth

To check out the instrument's optics and sensors, in January 2022 the ASU team took test images with the E-THEMIS camera from the rooftop of the Interdisciplinary Science and Technology Building 4 (ISTB4) on ASU's Tempe campus. The images show Sun Devil Stadium and “A” Mountain, among other local landmarks.

The instrument worked perfectly, with E-THEMIS making temperature-sensing images at midday, in late afternoon and after sunset. As designed, these clearly revealed how the temperature of the buildings and landscape responded to changes in sunlight as the day progressed, and they show the features cooling after sunset.

Surviving a rough neighborhood

When Europa Clipper arrives at Jupiter, it will encounter an extremely harsh environment. The giant planet poses major difficulties for any spacecraft operating in its vicinity. First, it's cold out there because Jupiter orbits more than five times farther from the sun than Earth, and sunlight has less than 4% the strength it has at Earth. But the biggest problems come from Jupiter's severe radiation environment.

The most massive planet in the solar system, and rotating more than twice every 24 hours, Jupiter spins out a large and powerful magnetic field. This creates a zone of trapped radiation around the planet similar to the Van Allen radiation belts around Earth, but thousands of times stronger. Europa Clipper must fly through this radiation zone again and again over the course of its mission.

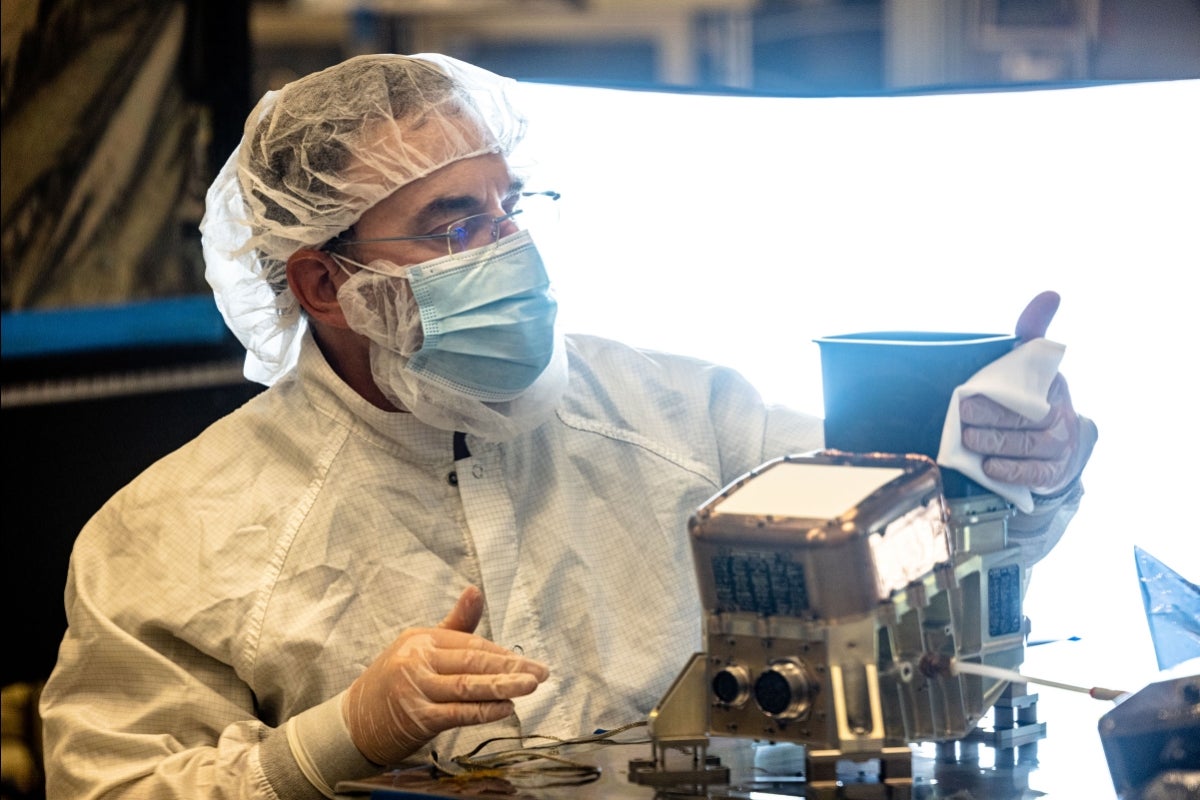

Greg Mehall is the lead project engineer for E-THEMIS. He explains, "The extreme radiation environment at Europa gave far more design challenges for the ASU engineering team than on any previous instrument we've developed."

Left unprotected, he says, the high levels of trapped electrons and protons in Jupiter’s magnetic field would cause serious damage to traditional flight instrument hardware.

"We had to use dense shielding materials, such as copper-tungsten alloys, to provide the necessary protection from the expected radiation," he says. "And to ensure that E-THEMIS will survive during the mission, we also carried out radiation tests on the instrument's electronic components and materials."

Then came the pandemic

Besides the engineering hurdles, the team had to build and test E-THEMIS during the pandemic.

In the workshops and clean rooms, Mehall explains, "We took all the safety precautions we could — everybody masked, we wiped down surfaces regularly, and we limited contact among ourselves."

Christensen adds that due to the pandemic requirements, "We had to go to two shifts, with one group of people coming in the morning to do part of a process. Then in the afternoon another group would come in to inspect the work. It was just horribly inefficient compared to our normal workflow."

He estimates that dealing with all the pandemic difficulties added at least five to six months to building and testing the instrument.

As E-THEMIS was being prepared for shipment to JPL, Christensen said, "Europa may be the most dynamic place where our group has ever sent a science instrument. And knowing that we're building a thermal camera to study a moon with an ocean that could harbor life has certainly kept everyone excited through all of the hard work and challenges."

In addition to Christensen and Mehall, the E-THEMIS engineering team includes Saadat Anwar, Courtnie Besich, Heather Bowles, Zoltan Farkas, Tara Fisher, Andrew Holmes, Ian Kubic, Edgar Madril, Bill O’Donnell, Carlos Ortiz, Dan Pelham, Mehul Patel, Nick Piacentine and Rob Woodward.

More about the mission

Missions such as Europa Clipper contribute to the field of astrobiology, the area of interdisciplinary research on the variables and conditions of distant worlds that could harbor life as we know it. While Europa Clipper is not a life-detection mission, it will conduct a detailed reconnaissance of Europa and investigate whether the icy moon, with its subsurface ocean, has the capability to support life. Understanding Europa’s habitability will help scientists better understand how life developed on Earth and the potential for finding life beyond our planet.

Managed by Caltech in Pasadena, California, JPL leads the development of the Europa Clipper mission in partnership with the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Planetary Missions Program Office at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, executes program management of the Europa Clipper mission.

More information about Europa can be found at europa.nasa.gov.

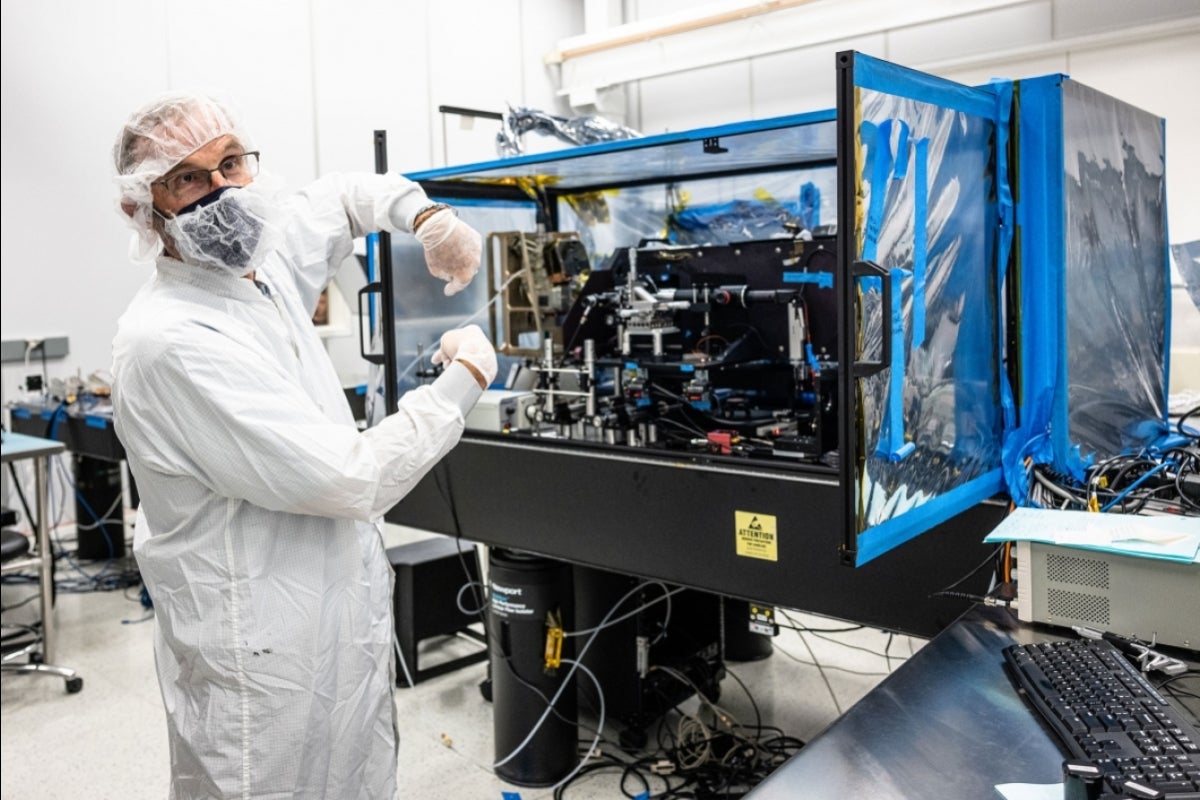

Top photo: Engineers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory prepare E-THEMIS for a series of function tests upon its arrival at JPL. Photo by NASA/JPL-Caltech

Written by Robert Burnham, science writer

More Science and technology

Podcast explores the future in a rapidly evolving world

What will it mean to be human in the future? Who owns data and who owns us? Can machines think?These are some of the questions pondered on a newly launched podcast titled “Modem Futura.” Co-…

New NIH-funded program will train ASU students for the future of AI-powered medicine

The medical sector is increasingly exploring the use of artificial intelligence, or AI, to make health care more affordable and to improve patient outcomes, but new programs are needed to train…

Cosmic clues: Metal-poor regions unveil potential method for galaxy growth

For decades, astronomers have analyzed data from space and ground telescopes to learn more about galaxies in the universe. Understanding how galaxies behave in metal-poor regions could play a crucial…