Citizen scientists help map ridge networks on Mars

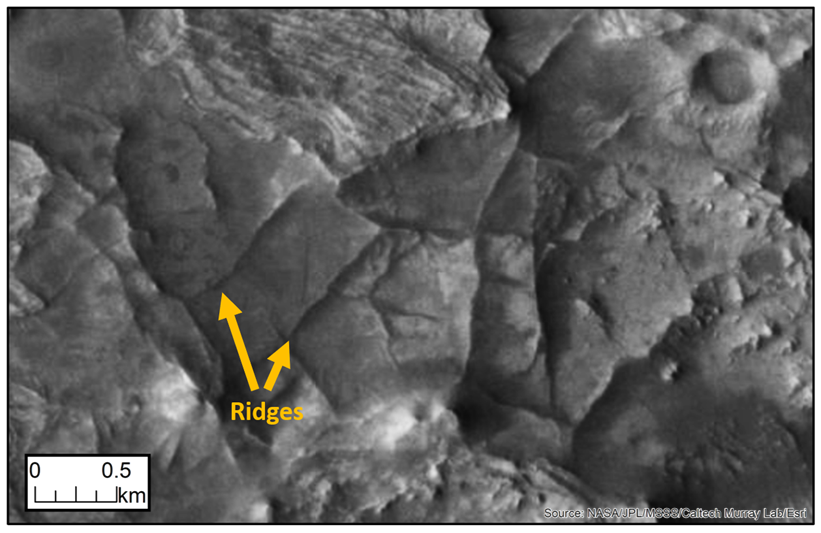

Unusual ridge networks on Mars may provide clues about the history of the Red Planet. Credit: NASA/JPL/MSSS/Caltech Murray Lab/Esri

Over the last two decades, scientists have discovered unusual ridge networks on Mars using images from spacecraft orbiting the Red Planet. How and why the ridges formed and what clues they may provide about the history of Mars has remained unknown.

A team of scientists, led by Aditya Khuller of Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration and Laura Kerber of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, set out to learn more about these ridges by mapping a large area of Mars with the help of thousands of citizen scientists.

Their findings, which have been recently published in Icarus, show that the ridges on Mars may hold fossilized records of ancient groundwater flowing through them.

How the ridge networks were formed on Mars has remained a mystery ever since they were found from orbit. Scientists have determined that there are three stages that were involved to create the ridges, including polygonal fracture formation, fracture filling and finally erosion, which revealed the ridge networks.

To learn more about these ridges, the team combined data from the NASA Mars Odyssey orbiter’s THEMIS camera and the Mars Reconnaissance orbiter’s CTX and HiRISE instruments. Then, they deployed their citizen scientist project using the platform Zooniverse.

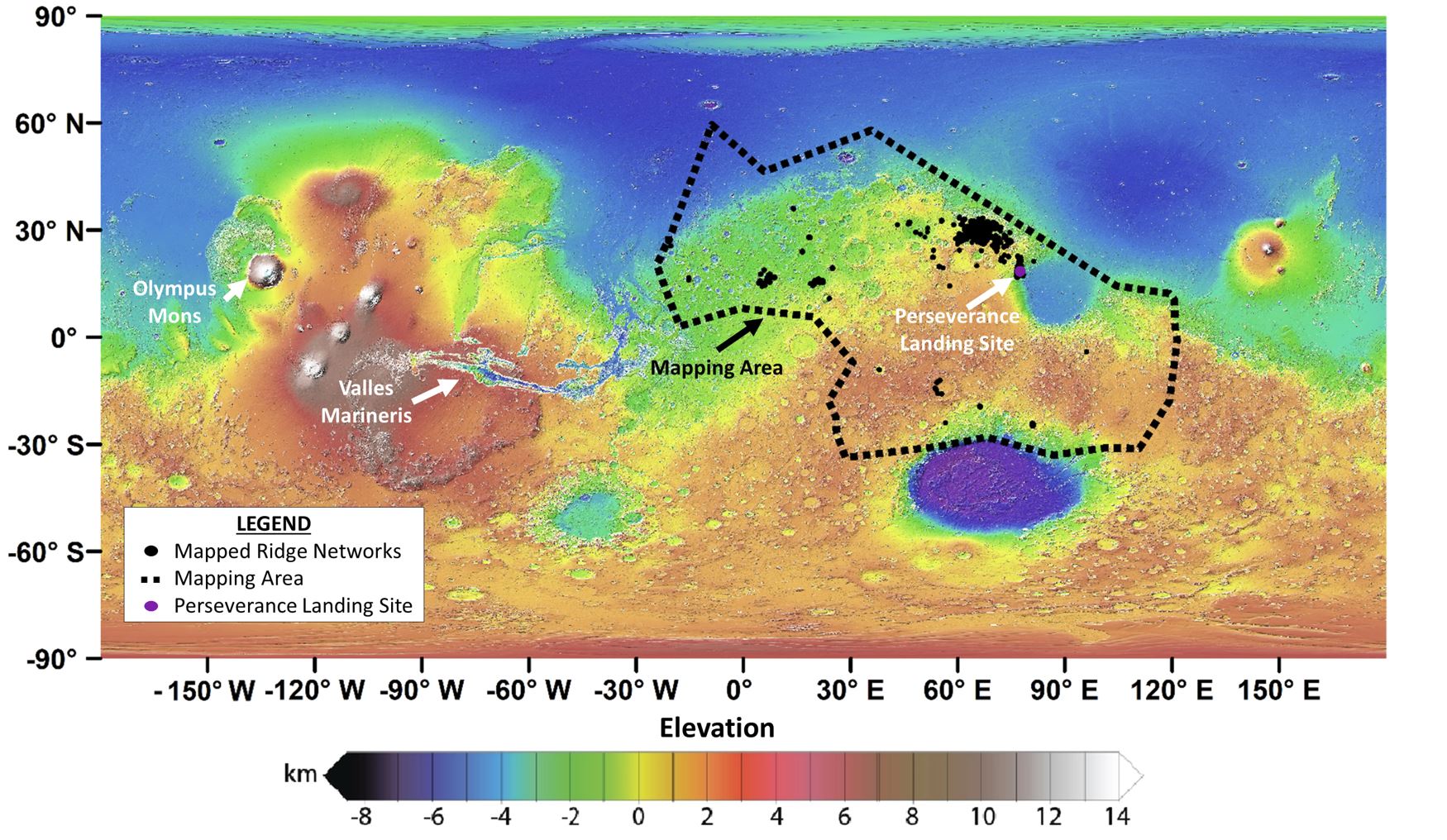

Nearly 14,000 citizen scientists from around the world joined in the search for the ridge networks on Mars, focusing on an area around Jezero Crater, where NASA’s Perseverance rover landed last February. Ultimately, with the help of the citizen scientists, the team was able to map the distribution of 952 polygonal ridge networks in an area that measures about a fifth of Mars’ total surface area.

Map of polygonal ridge networks (black dots) identified in mapping area (dashed black outline), covering approximately a fifth of Mars’ total surface area. The Mars Perseverance rover landing site is shown in purple. Background: Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter Elevation Map. Credit: NASA/JPL/GSFC.

“Citizen scientists played an integral role in this research because these features are essentially patterns at the surface, so almost anyone with a computer and internet can help identify these patterns using images of Mars,” Khuller said.

Most of the ridge networks (91%, or 864 out of 952) that were analyzed are located in ancient, eroded terrain that is approximately 4 billion years old. During this time period, Mars is believed to have been warmer and wetter, which might be related to how these ridges form.

Previous research in this area has shown that those ridges which were not covered with layers of dust showed spectral signatures of clays. Since clays form from weathering in the presence of water, this suggested to the research team that the ridges may have been formed by groundwater. While the abundant surface dust in these regions makes it difficult to check whether the newly mapped ridge networks by Khuller and Kerber’s team also contain clays, their similarities in shape and dimension suggest that they might form from similar groundwater processes.

Example of a polygonal ridge network showing approximately 10-meter thick, intersecting ridges enclosing irregular 100–200 meter-sided polygons. Credit: NASA/JPL/MSSS/Caltech Murray Lab/Esri

This discovery helps scientists "trace" the footprints of groundwater running through the ancient Martian surface and determine where it was suitable, during that time 4 billion years ago, for liquid water to be flowing near the surface.

“We hope to eventually map the entire planet with the help of citizen scientists,” Khuller said. “If we are lucky, the Mars 2020 Perseverance rover might be able to confirm these findings, but the nearest set of ridges is a few kilometers away, so they might only be visited on a potential extended mission.”

Additional authors on this study include Megan Schwamb of Queen’s University Belfast; Fernando Nogal, Sylvia Beer, Ray Perry and William Hood of the Planet Four: Ridges Citizen Science Team; Klaus-Michael Aye and Ganna Portyankina of the University of Colorado, Boulder; and Candice Hansen of the Planetary Science Institute.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…