ASU scientists make new discoveries about TB transmission between seals, humans

Seals fight for the best spot in Islas Ballestas, Peru. Photo courtesy Unsplash

In 2014, Arizona State University scientists published research about pre-contact tuberculosis (TB) found near the coast in South America. The ancient DNA showed the strain of TB found in the human remains was not similar to modern-day human TB strains, but actually matched the TB variant found in seals and seal lions, Mycobacterium pinnipedii.

“Did the people on the coast get it directly from seals, or did it jump and spread from human to human?” said ASU anthropological geneticist and Regents Professor Anne Stone. “That was something that we couldn't exactly say, because all the sites from our first study were fairly close to the coast.”

Now there is new data from Stone, and bioarchaeologist and Regents Professor Jane Buikstra, both at ASU's School of Human Evolution and Social Change. The data showed the transmission of the “seal” TB strain could have gone from seal to human, and then human to human.

Stone said the project, which took several years, was a collaboration between multiple scientists, including collaborators at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

The initial research done in 2014 focused on human remains that were found near the coast of Peru. The new DNA was from three sites, all more inland. One sample was from the Osmore valley in Peru; the other two samples were from two archaeological sites in the highlands (above 2,000 meters in altitude) under modern Bogotá, Colombia, Stone said.

“We don’t have evidence for seal bones at the sites,” Stone said. “And importantly, in doing the radiocarbon dating and nitrogen isotope analyses, we don’t see evidence of seafood in the diet. Nitrogen can be used to identify seafood in the diet; it skews nitrogen levels.”

With this new information, the anthropologists believe this TB strain could have morphed from traveling from seal to human, to traveling from seal to human to human. Another theory is that the seals could have spread the TB to other animals, such as guinea pigs or llamas, which in turn spread it to humans far away from the coast.

Why is this important, and what impact does it have for humans today?

Stone and colleagues state in the paper that in 2018, prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, tuberculosis was the number one cause of death by an infectious pathogen.

“I think it’s important because we are trying to understand what are the circumstances and evolutionary changes that foster the successful jump of a pathogen from an animal to a human,” Stone said. “And what are the consequences of that? You can see that very clearly today because of the COVID-19 pandemic.”

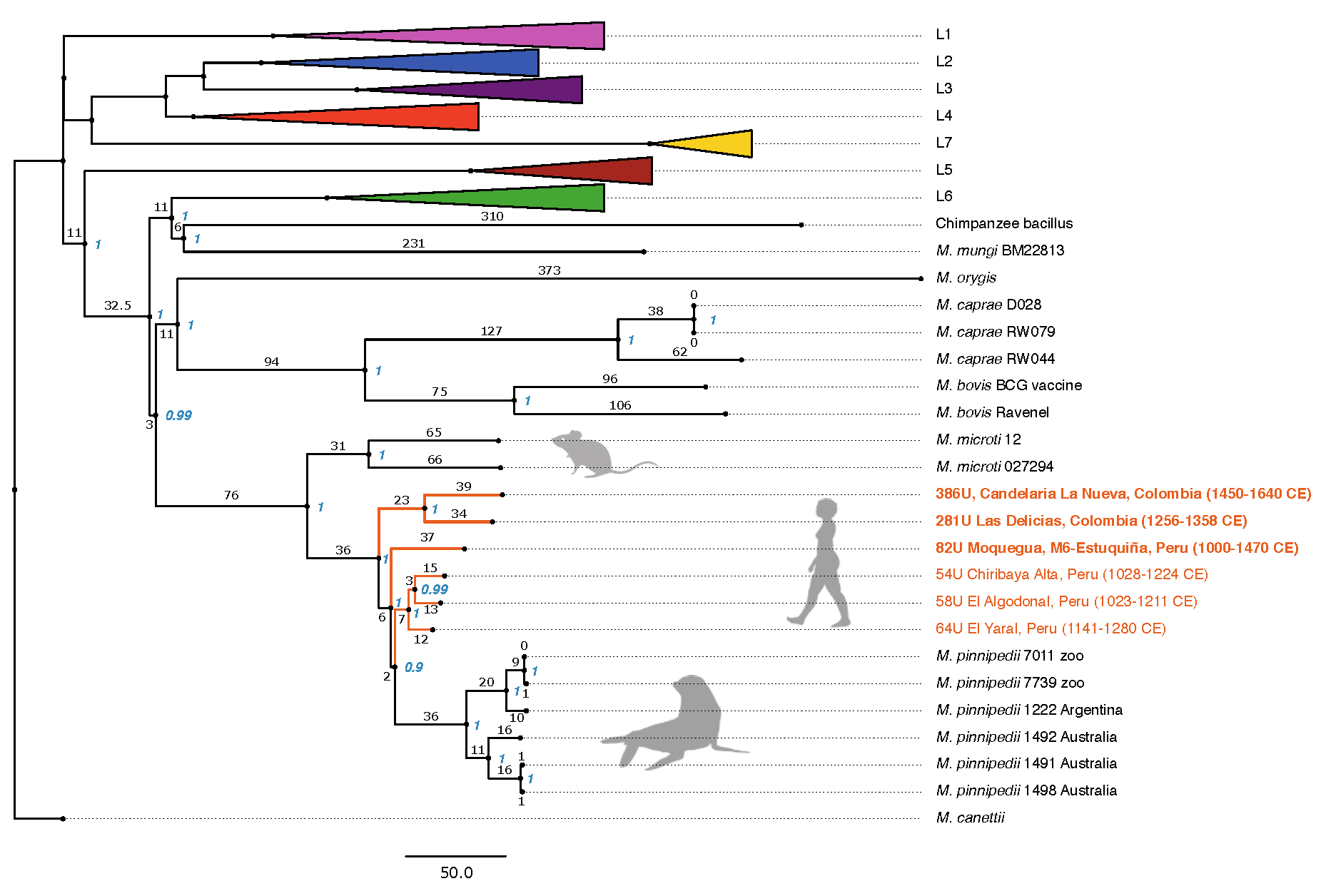

The tree was constructed using the full dataset of 266 MTBC genomes, including the six ancient genomes that are highlighted in orange. Genomes 82U, 281U and 386U are marked in bold, and BAM files filtered for spurious reads were used for SNP calling before tree construction. The tree is based on 14,262 positions out of a possible 44,235, with all missing and ambiguous sites excluded, using 500 bootstrap replicates. Bootstrap support (blue) and branch lengths are marked. Human-adapted lineages 1–5 and 7, and human-associated L6 strains have been collapsed. The three ancient genomes fall together with other ancient Peruvian genomes within the M. pinnipedii clade. Graphic courtesy Nature Communications

From field to laboratory

The first step in projects like this involve expertise from bioarchaeologists and analyzing human remains, something ASU scientists do with care and consideration.

Buikstra, who is credited with forming the discipline of bioarchaeology, said community engagement in her projects and research is essential. In this project, Peruvian students and community members were all very involved. Some are now centrally placed as museum directors and other key personnel who protect and conserve Peru’s archaeological materials, she said.

She also said sites excavated for these projects were being destroyed by the expansion of the city of Ilo and by looters.

“We also regularly gave presentations to the communities about our research, and generally engaged the public as much as possible,” Buikstra said.

Buikstra became interested in ancient TB as a graduate student at the University of Chicago while studying with ASU Professor Emeritus Charles Merbs. Her work in Peru spans decades, beginning when she first started to research how TB was infecting Americans before they came in contact with Europeans.

“I worked systematically, comparing the range of skeletal changes in the ancient North American materials and published differential diagnoses during the 1970s and early 1980s for North American remains of ancient people,” Buikstra said.

There were skeptics who questioned her work because she wasn’t a medical doctor and because, at that time, she was a woman working in a male-dominated field. She also said the standing theory of TB was that it came from cattle during the intensification of pastoralism in the Eastern Mediterranean, about 10,000 years ago.

“So I took advantage of an opportunity to develop a bioarchaeological excavation and analysis program in southern Peru in 1989, where I knew the preservation of mummies and bone is among the best in the world, due to the presence of the Atacama desert, the world’s driest,” Buikstra said.

Buikstra’s project attracted fellow experts like the late paleopathologist Arthur Aufderheide, molecular biologist Wilmar L. Salo and other anthropologists and archaeologists. The projects identified TB in ancient remains and led to more questions and more research, like the current publication.

She said understanding the spread of diseases and pathogens between species is extremely important, even today. Pointing out the pathogens can jump, morph and become more resistant.

“Therefore, public health measures are crucial in ensuring the disease is eradicated in individuals and communities,” Buikstra said.

“Assuming that our advanced technology will keep us safe is a fallacy, as we have seen recently with SARS and COVID-19,” she added. “I think (we need to appreciate) the long history of our interactions with pathogens and that humans must always be vigilant, as ignoring the possible long-term impact of inaction can encourage disease spread that ultimately is maladaptive for other species as well as our own.”

Finding the DNA sequences

Tanvi Honap, doing lab work in the ancient DNA laboratory at the University of Oklahoma. Photo by Sarah Johnson

After samples were collected in the field by Buikstra, the work began in the Stone Lab at ASU. Tanvi P. Honap is an assistant research professor at the University of Oklahoma and an author on the paper, “Geographically dispersed zoonotic tuberculosis in pre-contact South American human populations,” now published in Nature Communications. Honap was a PhD candidate at ASU and worked in Stone’s lab during the project.

Honap shared more about the technical process of the work done in the lab.

Question: How long did this research take you and your team?

Answer: At the time, the team had just finished analyzing the data from the Bos et al. 2014 paper and realized that pre-contact era coastal Peruvian individuals were infected with the seal TB variant (Mycobacterium pinnipedii). Upon realizing that, we wanted to focus on skeletal TB cases from non-coastal individuals to see if they were infected by the same TB variant. Over the next couple of years, Dr. Jane Buikstra traveled to Colombia and collaborated with the Instituto Colombiano de Antropología e Historia (ICANH), Colombia, to study and select skeletal TB cases from inland sites for ancient DNA analysis.

Dr. Åshild Vågene worked on some of these cases at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History (MPI-SHH) in Germany, and I worked on some here at ASU.

The process of screening all of the bone samples for TB DNA was a very long process and involved multiple steps of lab work, sequencing, data analysis and data authentication. We finally narrowed down samples we thought had the best TB DNA preservation for trying out a whole-genome enrichment for TB DNA.

I went to MPI-SHH in 2016, and together with Dr. Vågene, we conducted the enrichment experiments and generated the genome data. Then, we had to analyze the genome data, and we also had to repeat sequencing in order to get sufficient TB genome coverage. All in all, this was quite a lengthy process, but at the end of it, we had recovered three new ancient M. pinnipedii genomes from inland individuals.

Q: What is a key takeaway for a layperson from this research? How does this affect the general population today?

A: Today, TB is the second-most common cause of death due to an infectious pathogen, but most of these cases are caused by human-adapted TB strains. But even today, we do not have a good idea of which wild animal species carry TB and how virulent such TB variants might be for humans. Our research shows that complex TB transmission chains, involving multiple host species, existed a thousand years ago. So given today’s highly interconnected and globalized world, the risk of potentially virulent animal TB variants “jumping” into humans and causing epidemics should not be underestimated.

Q: Was there anything that surprised you or that you weren't expecting from this project?

A: In terms of the findings themselves, it was a bit of a surprise to find that the ancient M. pinnipedii diversity that we see in the individuals from South America is not the result of a single zoonotic transmission event from seals to humans living on the coast followed by further spread to the inland peoples. Instead, our analyses showed that different M. pinnipedii strains were introduced to the coastal peoples on multiple occasions.

More Science and technology

ASU forges strategic partnership to solve the mystery of planet formation

Astronomers have long grappled with the question, “How do planets form?” A new collaboration among Arizona State University,…

AI for AZ: ABOR funds new tools for state emergency response

A huge wildfire rages in the wilderness of Arizona’s White Mountains. The blaze scorches asphalt and damages area bridges,…

ASU researchers engineer product that minimizes pavement damage in extreme weather

Arizona State University researchers have developed a product that prevents asphalt from softening in extreme heat and becoming…