ASU report finds homeless young adults at risk for labor, sex trafficking

A new report from Arizona State University has found that among homeless young adults who were surveyed, about 40% had experienced exploitation – sex trafficking or labor trafficking. And the young people who were trafficked were more likely to be addicted to drugs or alcohol and have anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

The report, the "2021 Youth Experiences Survey (YES) Study: Exploring the Human Trafficking Experiences of Homeless Young Adults in Arizona," is the eighth one released by the ASU Office of Sex Trafficking Intervention Research.

Dominique Roe-Sepowitz, an associate professor in the School of Social Work, is director of the office, which analyzes data to create interventions for sex and labor trafficking.

Roe-Sepowitz said that in 2014, her office was meeting with an agency that was providing outreach, shelter and drop-in center services for homeless young people in Arizona.

“We were trying to figure out if the two exist at the same time – are homeless kids particularly vulnerable to sex or labor trafficking? We didn’t know the answer,” she said.

They developed an eight-page survey, distributed it to agencies who serviced homeless young adults, and gave the agencies $5 gift cards to hand out to the survey participants.

“In 2014, we found that 25%, or one out of four kids, were sex trafficked. We were unsure if that was what we would see across time.

“The next year, we found that 36%, or one out of three homeless young adults in this study, identified as a victim of sex trafficking, and it’s been about 25% to 35% each year.”

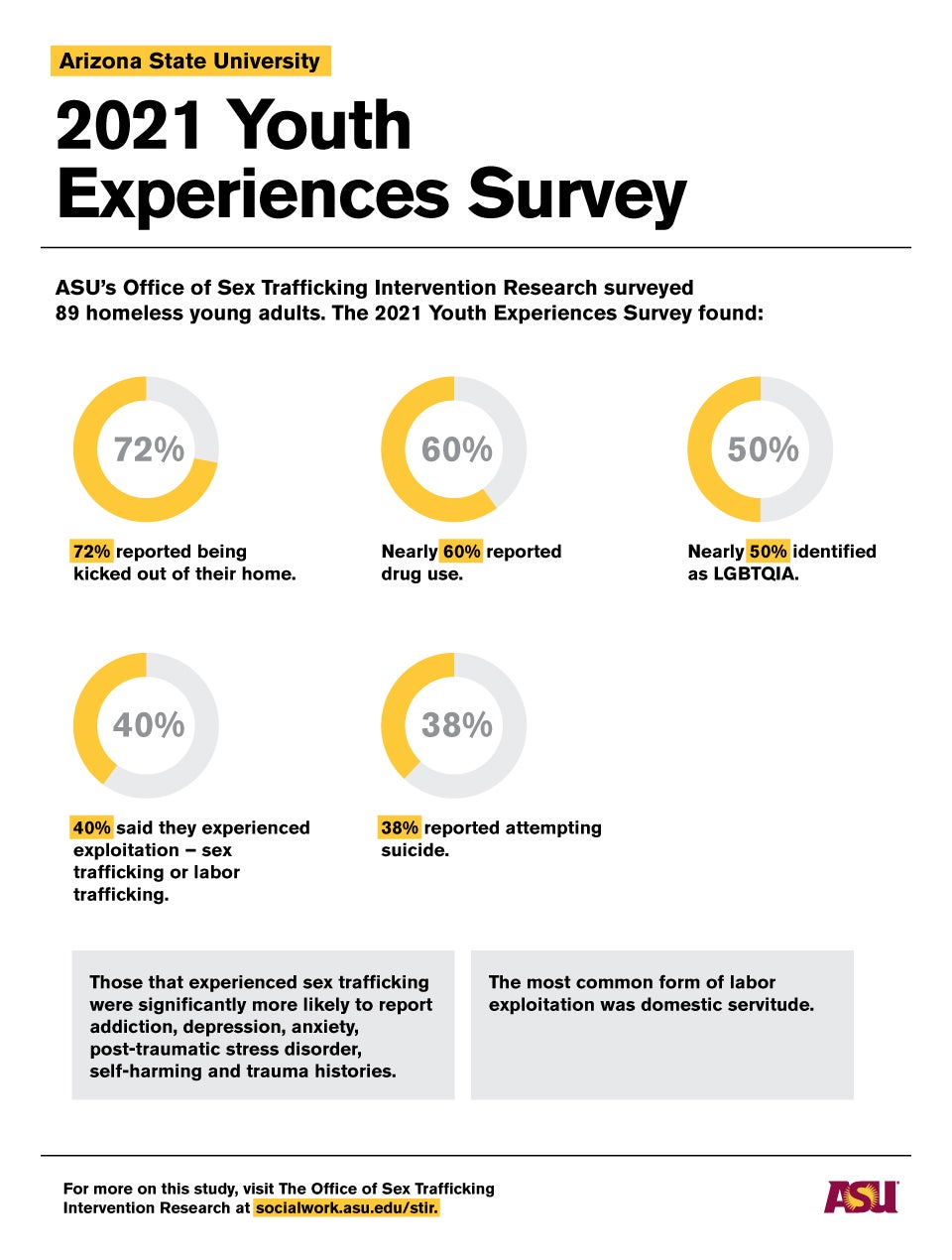

The 2021 Youth Experiences Survey tracked the responses of 89 young adults ages 18 to 25 who were clients of agencies that provide services to homeless people. The survey found:

• 72% reported being kicked out of their home by their families.

• Nearly 50% identified as LGBTQ.

• Nearly 60% reported drug use, most commonly marijuana.

• 40% said they experienced exploitation – sex trafficking or labor trafficking.

• Those that experienced sex trafficking were significantly more likely to report addiction, depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, self-harming and trauma histories.

• The most common form of labor exploitation was domestic servitude.

• About 62% reported a mental health diagnosis, most commonly depression and anxiety.

Roe-Sepowitz said the results show the need for strategic intervention for children who are at risk of homelessness.

Roe-Sepowitz answered some questions from ASU News about the report.

Question: What is labor trafficking?

Answer: Labor trafficking is not very visible. It has been under-researched and hard to see in our community. We’ve had only two convictions since 2011 in Arizona.

Labor trafficking has been confused with human smuggling. People think a person brought over the border by a coyote or in a truck is a human trafficking victim and that is not so. Smuggling is a crime against a country. Trafficking is a crime against a person by threatening a person to get them to do labor and withholding freedom from them.

In one recent case, a man from Gilbert (Arizona) was arrested who has a family company that is a traveling carnival. He had 10 Mexican nationals brought into the U.S. lawfully with work visas, then took their identification and their passports, made them live in squalor, didn’t feed them or pay them and withheld their freedom. One went to the police, who put a wire on him, and they had a confession by the perpetrator. You see this pattern in agriculture, in hotels and in people’s homes for domestic servitude.

In prostitution-based sex trafficking, you have to see someone to buy them. It’s outward-facing. But you could have someone working in a home for 20 years and no one knows they exist.

Q: How is the ASU Office of Sex Trafficking Intervention Research intervening with labor trafficking?

A: We had a symposium (last year) with an international audience. Hundreds attended. We were hoping to make sure that people know what labor trafficking is and how communities can respond.

Since June, we’ve been working with eight other agencies in the community to do outreach for labor trafficking victims and exploited victims at places like Home Depot, where day laborers may not know their labor rights.

We have conducted national studies on labor trafficking with surprising results, including finding child labor in the U.S. We also are working with faculty in computer sciences at ASU on an an NSF grant looking at parallel networks of human trafficking and drug trafficking. We’ve been working with the Phoenix police department and the Las Vegas police departments to help with data-driven policing on trafficking

Q: How do the 2021 Youth Experiences Survey results compare with previous years?

A: What we have seen consistently is that LGBTQ youth are disproportionately represented in the victim group. They are disproportionately represented in the young adult homeless population at 50%, and when you ask about sex trafficking, it’s 60%.

We’re learning in each study that we need to do prioritization of how we support kids. This study is used by the medical community to figure out what’s happening. Over the last few years, medical issues that youth are facing are dental and vision because ACHSSS does not pay for vision or dental services outside of crisis services.

We’ve seen other changes over time. Who is the exploiter? Over the past few years, we have found the trafficker is more likely to be friends, while previously, it was boyfriends or girlfriends.

A few years ago, the top reason for exchanging sex was for food. Food insecurity is a huge issue among homeless young adults. Now the most common reason for being sex trafficked is needing a place to stay.

Interestingly, over the last three years, services for homeless young people in Maricopa County have been almost completely extinguished. There are less than 100 beds at any one time, and over 1,000 identified as needing beds.

The report has become like a rule book for us to say, “What do we need to prioritize?”

Q: Why are LGBTQ young adults over-represented?

A: That’s a good question. We’re looking at investing time and money into that.

Part of it, we believe, is that they’re more likely to be kicked out of their homes. There is substance abuse and mental health challenges we found in that group over and over in the study that show the complications in working or going to school.

We have had cases in Arizona where the naiveté of LGBTQ youth was exploited. There was a high schooler who was kicked out by mom, who was religious. He lived with an adult he met on Facebook, a guy in his 40s, and that guy convinced the 17-year-old that in the “gay lifestyle,” you have sex with lots of people and all the money goes to the boyfriend. He exploited what this child didn’t know.

So we’re terribly concerned about this.

Q: How has the pandemic affected your work?

A: Through the pandemic, we worked really hard with agencies and put the survey online. Historically, the survey was only on paper. We only had 89 responses to the survey because July was a tough time in Arizona.

Our hope is we get back to 200 or 215 responses like we did in the first years.

We know the housing crisis has exacerbated youth homelessness. Who will rent to an 18-year-old who started a job two weeks ago?

Everyone is fighting for the same housing.

The pandemic has also forced the anti-trafficking field to become more innovative and creative. We have developed a number of new programs in direct response.

Q: Are the young adults who are surveyed from around the state?

A: We do try to do statewide, but we can’t find partners in Yuma or Flagstaff or Prescott. We try to reach out and say it’s free to them. We do get funding from the McCain Institute. But we’ve had a tough time getting this to be statewide.

We do it over a short time to keep the pressure low on staff, so it’s over two weeks in July. That also helps to prevent duplication, in case a client moves agencies during that time.

The community engagement is the reason this study works. Everything I do in my research office depends on our partners. I can’t go out and ask kids what’s going on in their lives. They have to trust whoever is asking them. We have such great relationships in the community that are producing such important research.

Q: You’re also the clinical director of Phoenix Starfish Place, a supportive residential community for victims of trafficking and their children, which opened four years ago. How is that going?

A: It’s been very stabilizing for the families. We’ve had very few leave over the past four years, which is a compliment, because they feel safe. We have learned that people don’t change quickly. We’re asking people to stop these behaviors and get a job and go back to school. We have someone about to graduate with an associate’s degree.

We opened a food pantry in the middle of the pandemic, before the child care supplement and food stamps went up. Before that, our clients weren’t making it through the week. Our food pantry is a critical part of our program now.

Q: Are students involved?

A: We’ve had 20 student interns over the last three years, from all over the university. My idea is that they learn about trafficking from me and our community partners, and even if they’re running a business or working on Wall Street, they’ll think about human trafficking in a new way.

Top image of Phoenix by Deanna Dent/ASU News