Graduate discovers a successful path is the one you create

This December, Adrienne Vescio will graduate with a double major in astrophysics and physics from the School of Earth and Space Exploration.

Editor's note: This story is part of a series of profiles of notable fall 2021 graduates.

When Adrienne Vescio transferred to Arizona State University, she was originally studying psychology to become a therapist but became increasingly aware it wasn’t a good fit. Enrolling in an introductory astronomy course to fulfill her natural science requirements, Vescio never imagined a career in astronomy. However, this December Vescio will graduate with a double major in astrophysics and physics from the School of Earth and Space Exploration.

“Though I've been interested in space sciences since I was a kid, I always struggled with math in school, so I didn't think I would be able to find success in it as a career,” said Vescio.

A former instructor helped her realize that an astronomer doesn't need to look like any particular kind of person, and that you don't need to have some sort of innate talent for math or science to explore and share the field.

“That, combined with the fact that astronomy is just plain neat, was all I needed to make the leap,” she said.

Vescio is originally from Mesa, Arizona, so attending an in-state university alongside her high school friends was a prime motivator to enroll with ASU. The learning environment was a prime motivator for keeping her here.

“The School of Earth and Space Exploration is an incredible school, and learning that ASU had such a great environment to grow new astronomers when I was considering looking elsewhere for the best program, seriously helped in convincing myself that it was the right place for me,” she said.

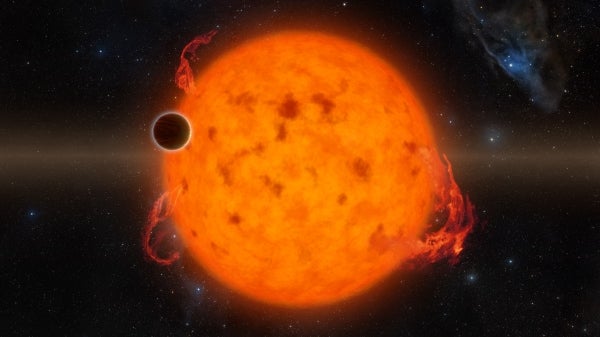

During her first year at ASU, Vescio began working with Professor and astrophysicist Patrick Young.

“Adrienne approached me about doing research her first semester at ASU,” said Young. “I was very fortunate she did. Her impeccable work on the properties of exoplanet host stars generated a new and very unexpected result with far-reaching implications.”

Taking advice from Young proved to be pivotal, especially in her upper-division courses.

“As an academic in our field, you need three things: your studies, your research and something else on the side to keep you sane,” she said. “Even if it feels like you have less and less time, you absolutely should not cut out all the things you do for fun to keep up. Those things are necessary to keep you going sometimes, so hold them close to home, however trivial they seem.”

Vescio believes success in astronomy doesn’t look the same for everybody. She spent time measuring herself against her peers and worrying about getting into grad school, only to realize that there is nothing wrong with creating your own journey.

“Some of the smartest people I've met with the coolest experiences didn't follow a cookie-cutter path of undergrad straight into grad school straight into a postdoc. If that's not how your career looks, it doesn't mean that you can't do research or be a ‘real’ astronomer,” she said. “Whether you apply for grad school during your senior year, apply five years later, or decide that academia just isn't for you at all — there's nothing wrong with any of it. Explore the different opportunities available and dive into what feels right with your best effort. As far as I'm concerned, that's what success looks like.”

Vescio shared a few thoughts about her time at ASU.

Question: What’s something you learned while at ASU — in the classroom or otherwise — that surprised you or changed your perspective?

Answer: This isn't necessarily a happy lesson, but something I learned while at ASU is that basically everyone doubts themselves. I'm fairly certain that the vast majority of the people I've met studying natural sciences have a serious case of impostor syndrome, even my peers and friends who I personally viewed as the smartest and most highly qualified! What this means, though, is that everyone struggles, even if it's hard to see it. You're probably so much better than you're telling yourself you are, and the fact that you've made it to the place you're at means that you've earned and deserve it! You haven't tricked anyone, so cut yourself a little slack.

Q: What was your favorite spot on campus, whether for studying, meeting friends or just thinking about life?

A: My favorite spot on campus is the engineering center courtyard area. It's generally pretty quiet and there's lots of shade and sun, depending on what you're looking for. I love the big tree they have in the middle and listening to the leaves rustle on windy days. It's super relaxing, and it's a nice change of pace to study outdoors sometimes.

Q: What are your plans after graduation?

A: I'm looking forward to jumping into the industry after graduating, leaning into my physics background to gain experience doing some level of spacecraft engineering. After spending some time exploring the field, I'd like to somehow find my way back into research — whether that be through moving around positions or by eventually deciding to go to graduate school.

Q: If someone gave you $40 million to solve one problem on our planet, what would you tackle?

A: Though it takes far more than money to make progress towards accomplishing this goal, I would want to put the cash towards tackling the problem of educational inequity. Something very close to my heart is teaching young, potential future scientists that they have all the mental tools they need to move into the sciences as a career if they so choose. Not all scientists are Einstein-level genius old men in lab coats, after all! These tools are too often obscured or disguised as something that is not enough to accomplish goals, and the troubles associated with generations of unequal opportunity encourage their neglect. Putting money and effort towards the goal of supplementing these young minds of huge potential with understanding, encouraging and engaging STEM educators and the opportunities they deserve to capitalize on their natural gifts results in a more diverse and exceptional field with more diverse and exceptional perspectives.

More Science and technology

ASU forges strategic partnership to solve the mystery of planet formation

Astronomers have long grappled with the question, “How do planets form?” A new collaboration among Arizona State University,…

AI for AZ: ABOR funds new tools for state emergency response

A huge wildfire rages in the wilderness of Arizona’s White Mountains. The blaze scorches asphalt and damages area bridges,…

ASU researchers engineer product that minimizes pavement damage in extreme weather

Arizona State University researchers have developed a product that prevents asphalt from softening in extreme heat and becoming…