New book by ASU professor tracks a terraced landscape first built by the Aztecs

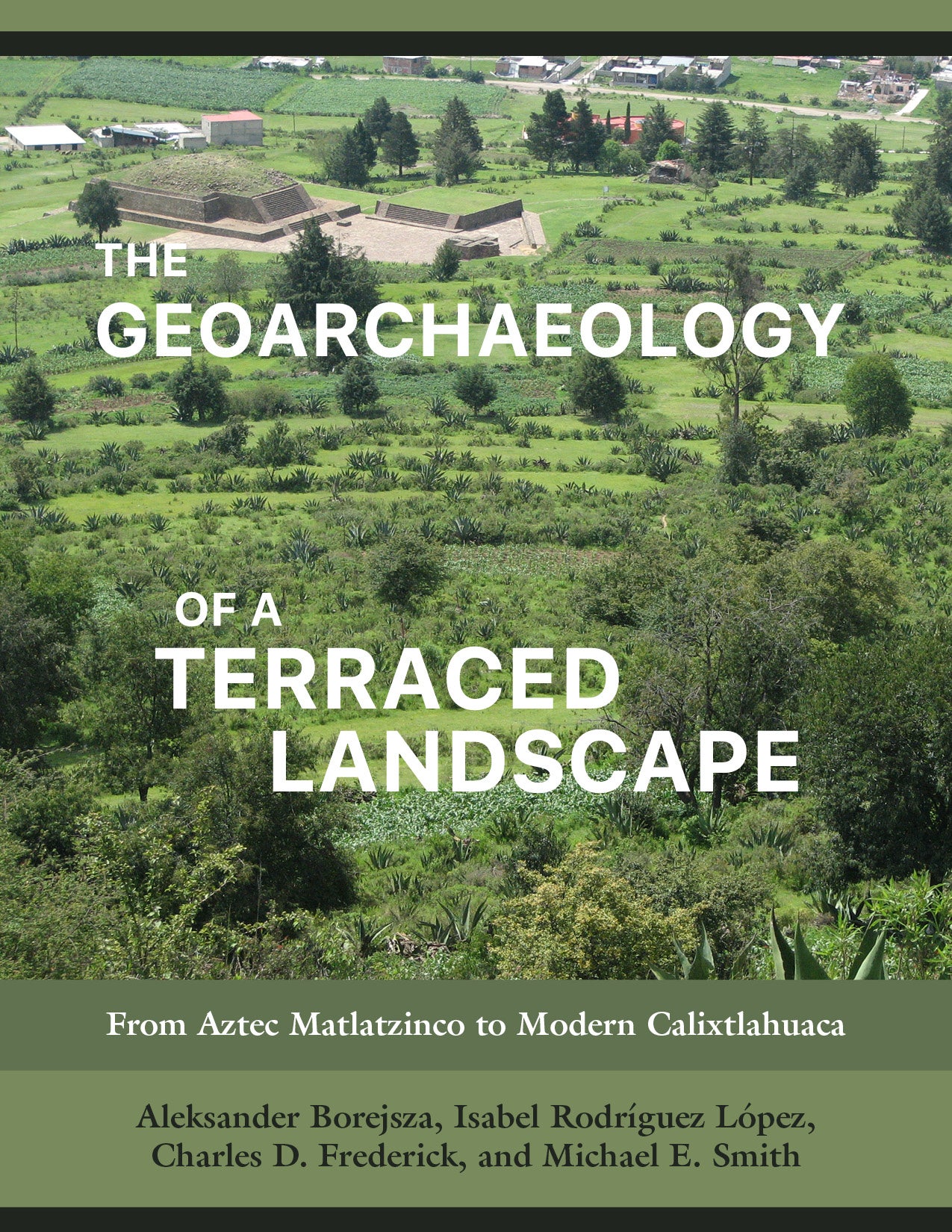

A temple in Calixtlahuaca, in central Mexico. Photo courtesy of Michael E. Smith

Searching for ancient Aztec houses, archaeologist Michael E. Smith began exploring the terraced landscape of Calixtlahuaca, in central Mexico, more than 15 years ago.

Hoping to study the homes of Aztec farmers, Smith and his team quickly found something surprising: the stair-like terraces built there by the Aztecs were modified by Mexican farmers hundreds of years later.

That discovery launched a years-long effort to trace the history of the site, starting with the Aztec period around A.D. 1100. What the team found, and what they learned about the research process along the way, is documented in a new book, “The Geoarchaeology of a Terraced Landscape.”

“This book is the most detailed analysis of ancient terracing certainly in central Mexico, maybe even all of Mesoamerica,” Smith said.

Terracing is used on hillsides and in mountain areas to make flat land for homes and farms. Slopes are flattened into level areas that often look like large staircases. Where there isn’t enough flat land, terracing gives farmers an area to grow crops. It also decreases erosion.

Smith, a professor with the School of Human Evolution and Social Change at Arizona State University, has studied the Aztecs extensively, publishing numerous journal articles and several books over his career. With approval from the Mexican federal government, he initiated the excavation in Calixtlahuaca to find and study homes — not those of kings and the elite, but those that would tell him more about daily life and society.

Because of his previous experience excavating agricultural terraces, Smith knew he would need expert help from a geoarchaeologist on the site. Geoarchaeologists study terrain, soil and rocks to help establish the history of a site like Calixtlahuaca. Geoarchaeologists Charles D. Frederick, a research fellow at the University of Texas, and Aleksander Borejsza, a professor at the Universidad Autónoma de San Luis Potosí, answered the call.

They discovered the Aztec terraces were modified and expanded within the last 100 years. When they showed Smith that the Aztec terraces were modified and not in their original form, he was initially “extremely bummed out.” But who did this? And why would they make the already flat terraces larger? The story of Calixtlahuaca after the Spanish conquest turned out to be more interesting than he first thought.

The team believes the answers are linked to the political history of the region. After the Spanish conquest, populations declined in central Mexico from disease. The people of Calixtlahuaca were moved to the city of Toluca, which became the area’s central city. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, large landowners in Mexico gained power and began pushing people off the best farmland.

When this happened, farming in Calixtlahuaca returned to the terraces built by the Aztecs. But Smith explains that the original terraces were too narrow for their oxen, horses and plows to turn; they had to modernize. The team believes farmers destroyed some of the higher terraces in order to widen the lower terraces and make enough room for their plows to turn around.

Another key finding for Smith was being able to date and determine what caused erosion in Calixtlahuaca.

Cover image courtesy of the University of Utah Press

There has been a long scholarly debate — the so-called Columbian debate — about the reasons for soil erosion in central Mexico. One side claimed the Aztecs overused the land because of population growth. The other theory is that sheep, brought in by the Spaniards, had eaten so much vegetation that it caused the soil to erode.

Smith and the team have a third explanation: They believe the erosion at Calixtlahuaca actually happened because the site was abandoned for several centuries after the Spaniards arrived.

“It looks like the reason for the erosion was not that sheep were brought in — there’s not much evidence for sheep in that area,” Smith said. “It’s that you have this terrace landscape that controls erosion, it controls runoff, and as long as you maintain it it’s fine. But when the system is abandoned, that’s when erosion happens.”

As evidence, they point to the fact that eroding terrace deposits completely covered the Aztec royal palace at the base of the mountain.

The book also serves as a road map for future studies of terracing. The authors discuss the range of research methods they used during the project, including excavation, soil analysis, radiocarbon dating and document reviews.

“The Geoarchaeology of a Terraced Landscape,” written by Borejsza, freelance archaeologist Isabel Rodríguez López, Frederick and Smith, published in October from the University of Utah Press.

More Arts, humanities and education

ASU professor's project helps students learn complex topics

One of Arizona State University’s top professors is using her signature research project to improve how college students learn…

Award-winning playwright shares her scriptwriting process with ASU students

Actions speak louder than words. That’s why award-winning playwright Y York is workshopping her latest play, "Becoming…

Exceeding great expectations in downtown Mesa

Anyone visiting downtown Mesa over the past couple of years has a lot to rave about: The bevy of restaurants, unique local shops…