Slow carb versus fast carb claims lack scientific evidence, says ASU professor

Humans have an intimate relationship with food. It’s complex too. What seems like a good food may in fact not be so good. What seems like a detrimental quality of a food may not actually matter too much. The important thing is to consider it as a whole.

For example, it has commonly been thought that the types of carbohydrates in a food could affect the amount of fat you store as a result of eating it. The idea is that if you regulated the types of carbs you consume, you may be more successful in taking the pounds off. This in essence is the debate of fast carb versus slow carb foods. Fast carb foods — for example, white bread, white rice and potatoes — cause a rapid increase in blood sugar when consumed, raising insulin in the body and contributing to the storage of fat. Slow carb foods — for example, bran flakes, some pastas, apples — only increase sugar in the blood modestly and have been thought to contribute to weight loss.

Now, an Arizona State University exercise physiologist says that rule of thumb has no scientific evidence to support it.

In a new paper in Advances in Nutrition, Glenn Gaesser, a professor in the College of Health Solutions, says though the glycemic index of a food can be important for certain conditions, putting weight on or taking it off are not among them. The article, “Does Glycemic index matter for weight loss and obesity prevention? Examination of the evidence on fast compared with slow carbs,” is based on an exhaustive literature review of existing studies on glycemic index.

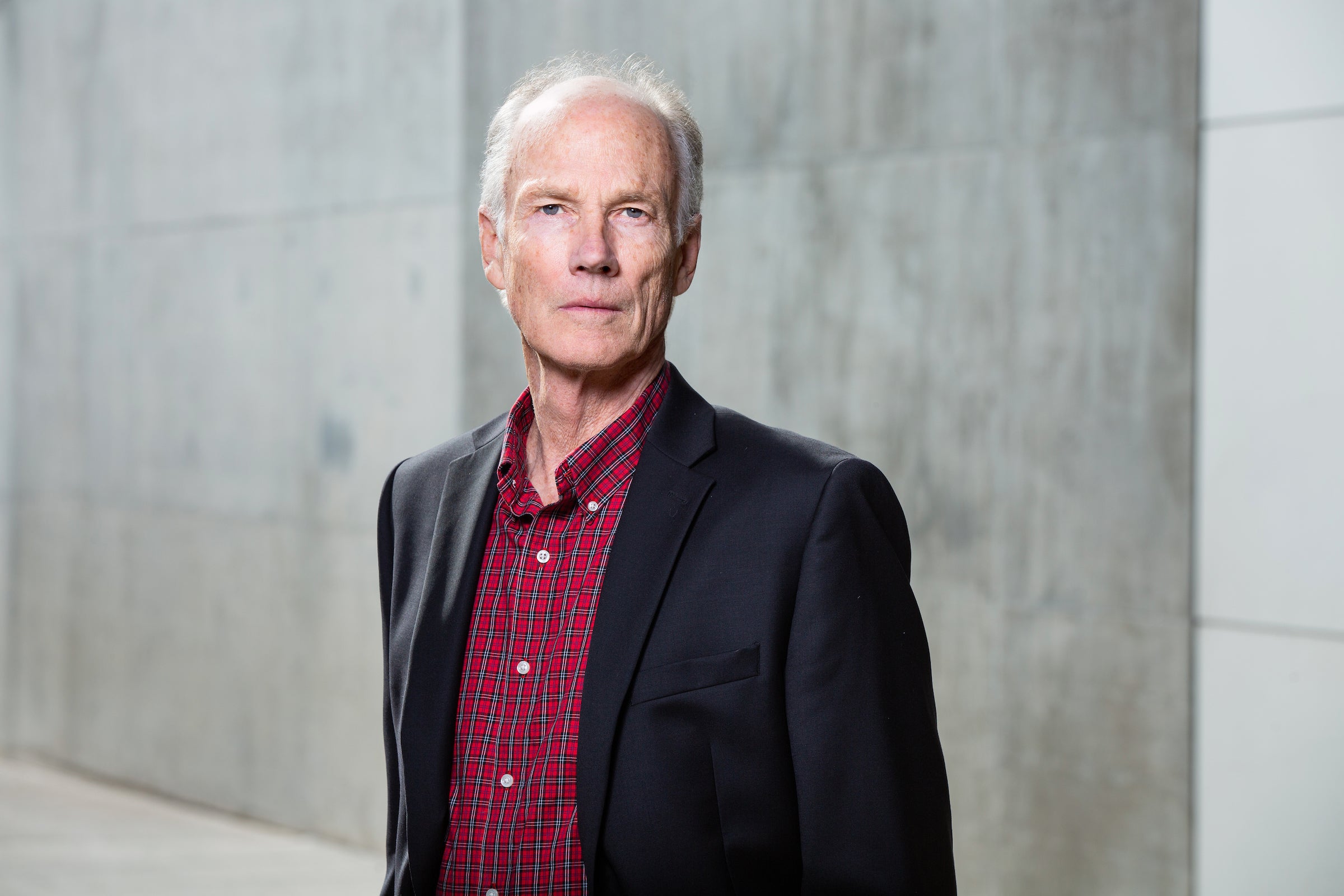

"The popular notion that fast carbs make us fat is a myth."

College of Health Solutions Professor Glenn Gaesser

“Popular consensus says that so-called fast carbs are making us fat, and that so-called slow carbs are better for weight loss,” Gaesser said. “The science, however, shows nothing of the sort.”

Gaesser answered a few questions about the new study, which included co-authors Julie Miller Jones of St. Catherine University, Minneapolis, and Siddhartha Angadi of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

Question: What are the key findings of this study?

Answer: The main finding of our study is that the dietary glycemic index is unimportant for obesity prevention and weight loss. Glycemic index refers to the effect that various carbohydrates have on elevating blood sugar. Some carbohydrates cause a rapid increase in blood sugar, and these are commonly referred to as fast carbs. Other carbohydrates, by contrast, result in a very modest increase in blood sugar, and these are commonly referred to as slow carbs.

Since blood sugar stimulates secretion of insulin, fast carbs invariably result in much greater increases in insulin, and insulin can accelerate storage of fat on the body. Because of this, a widely held belief among many in the nutrition world is that fast carbs make us fat, and slow carbs are better for weight loss. Our review of the literature demonstrated that there is absolutely no convincing evidence to support this view of fast and slow carbs. The popular notion that fast carbs make us fat is a myth.

Q: How did you determine that?

A: We performed a literature search to answer two basic questions: 1) Is glycemic index, i.e., the proportions of fast and slow carbs in the diet, a good predictor of body weight? And 2) Are low-glycemic index — slow carb — diets better than high-glycemic index — fast carb — diets for weight loss?

To answer the first question, we examined all relevant epidemiological studies that provided information on dietary glycemic index and body mass index (a measure of weight relative to height) of study participants. We found results from 43 different populations, with a total of nearly 2 million men and women. There was essentially no difference in body mass index of people who consumed a high-glycemic index diet compared to people who consumed a low-glycemic index diet. This was true for both men and women, young and old. Glycemic index appeared to be unimportant as a determinant of body weight.

To answer the second question, we examined all the meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials that compared low-glycemic diets and high-glycemic diets for weight loss. Similar to the results for the epidemiological studies, the randomized controlled trials showed that, with few exceptions, there was no benefit of low-glycemic diets for losing weight or reducing body fat.

Together, the evidence from epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials shows that slow carb diets are not superior to fast carb diets for weight loss and obesity prevention.

Q: What does this mean for the claims of slow carb diets?

A: It is important to note that our findings are specific to the issue of body weight. There are other health outcomes for which glycemic index may be important. For example, a number of epidemiological studies show that a slow carb diet is associated with lower risk of certain chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. So we are not saying the glycemic index is entirely unimportant for overall health. Our study just illustrates that glycemic index is unimportant for weight control.

Q: So, if slow carbs or fast carbs don’t affect weight loss, what should a person who wants to lose weight do?

A: The most important factor for weight loss is creating a calorie deficit, regardless of the composition of the diet. This can be achieved with virtually any diet. The problem is sustaining the reduced calorie intake. Long-term weight-loss maintenance is very challenging.

Exercise has been shown to be a good predictor of weight-loss maintenance and allows the dieter more flexibility and options with regard to food choices. Aside from weight-loss maintenance, exercise is an essential ingredient in a healthy lifestyle. It is also important to emphasize that the health benefits of a diet are determined more by the “quality” of the diet than the number of calories. Diets that include lots of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts and legumes invariably produce health benefits, even in the absence of weight loss.

Q: How does this affect our understanding of the food we eat and how it interacts with our bodies?

A: This is a difficult question to answer because of the tremendous variation among people with regard to how foods affect our bodies. We focused on carbohydrates, specifically how the glycemic properties of carbs impact body weight. In our review we looked at studies that examined the validity and reliability of measuring the glycemic index of foods. These studies showed that the glycemic index is a very imprecise measure of the glycemic response of a food when consumed as part of a meal, and that there is large variability among people with regard to glycemic responses to any given carbohydrate.

Also, the glycemic index of a food can change depending on a number of factors, including how it is prepared (cooked), the fiber content of the food, and the time of day that the food is consumed. For these reasons, we concluded that using glycemic index for purposes of weight loss or prevention of weight gain is not justified on scientific grounds. However, even though glycemic index does not appear to be important for weight loss and obesity prevention, it may be important for other health outcomes. There are some individuals for whom the glycemic index may be very important for controlling blood sugar levels. In this regard, the glycemic index may be useful for individuals with diabetes or abnormal glucose tolerance as a means to minimize large spikes in blood sugar after meals.

Top photo courtesy of Pixabay.com

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity of low-mass stars, has now passed its pre-shipment review by NASA.…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the transformation ASU is driving through its microelectronics research…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State University has developed a groundbreaking high-temperature copper alloy…