Arizona State University’s Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems has issued a new report on how the organic food market can be improved, and it's targeting the most powerful person in the free world — President Joe Biden.

His title is right there on the front cover: "The Critical To-Do List for Organic Agriculture: Recommendations for the President."

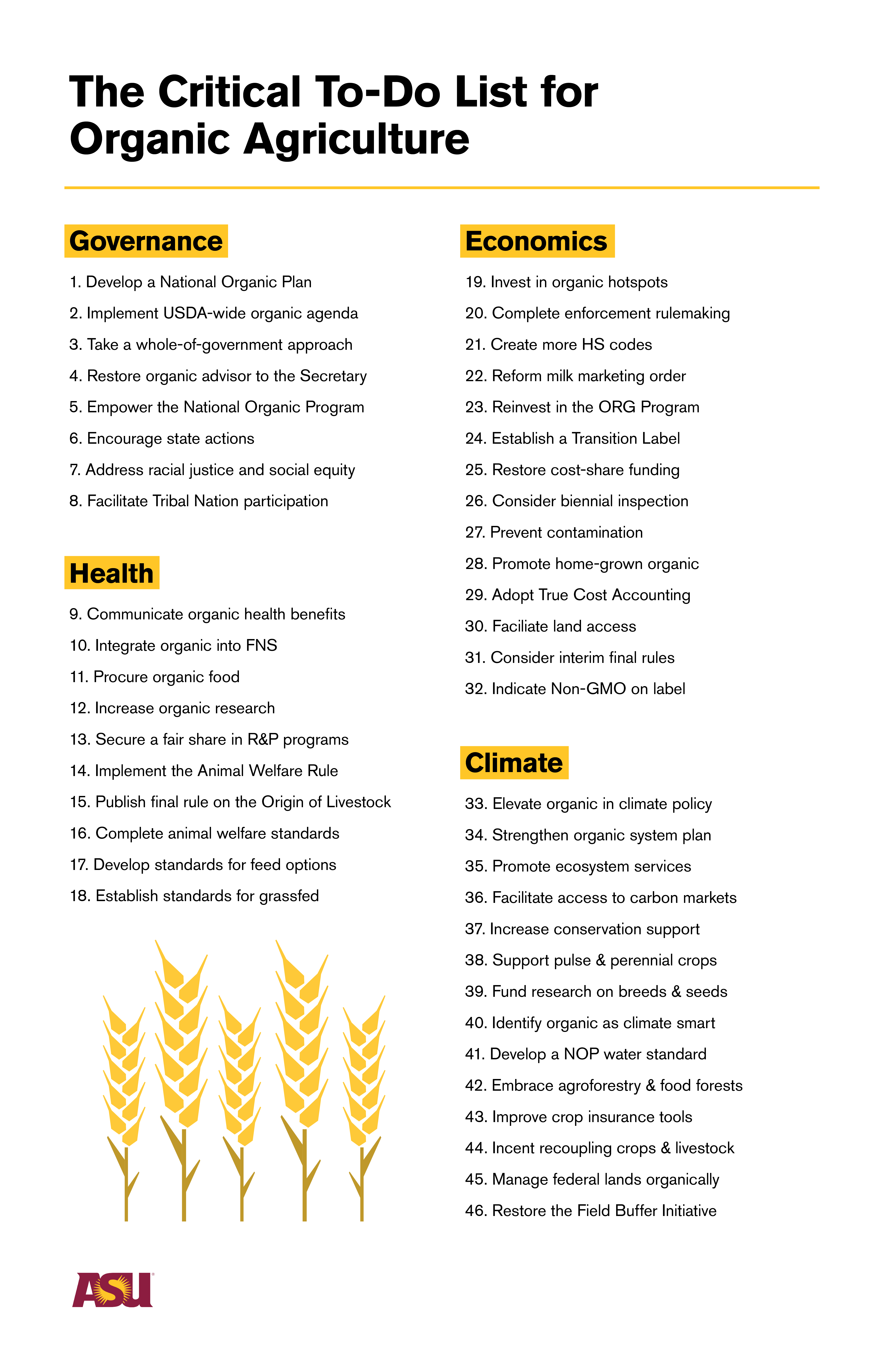

The 69-page report, which has 46 recommendations for Biden, is an outgrowth of discussions between the center, the Natural Resources Defense Council and Californians for Pesticide Reform. They spent the last two years working together to produce a comprehensive report based on cutting-edge science.

And it doesn’t just address food. It tackles climate change, research, supply chain, animal welfare standards, racial justice, social equity and enforcement.

The Swette Center decided to publish these recommendations in advance of the full report, given the interest of the new administration and Congress in pursing an organic agenda.

Kathleen Merrigan

ASU Now spoke to Kathleen Merrigan, executive director of the Swette Center and a senior sustainability scientist with the Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation, about the report’s recommendations and some key findings.

Question: Your report has 46 recommendations. Seems like a strange number. Was there a reason for this particular number?

Answer: Joe Biden is the 46th president of the U.S. and so we decided to have some fun and play with this number, along with many others in the report. For example, at the start we provide scene-setting numbers. The reader learns that it was 30 years ago that Congress passed the law that established national standards for organic food and, that after years of exponential growth, the U.S. organic market just hit $62 billion in 2020. Organic is sold by most grocers and 82% of Americans say they purchase at least some organic food. In our conclusion, we describe 36 of the recommendations as "low hanging fruit," and by this we mean that President Biden has the power today to implement most, if not all elements of these recommendations. Our goal was to identify easily achievable actions for the new administration that, if undertaken, would immediately power-boost organic agriculture. Now that the report is out, our job is to make sure it makes a difference. We are hard at work getting it into the inboxes of organic advocates and policymakers.

Q: There are several recommendations that relate to young and beginning farmers. Why this emphasis?

A: The average age of farmers in this country is 57.5 years, with a third of farmers over the age of 65. I know farmers in their 80s still milking cows, a really tough, 365-day a year job. The reality is that many farmers want to retire, but there is no one in the wings ready to take over their operations. The aging of America’s agricultural workforce is a very serious problem. We need to repopulate our working lands and rural communities with young people.

The good news is that organic is luring the next-gen into farming. Young people are interested in the environmental and health aspects of organic, but also the price premiums. The little bit more we pay for organic helps small-scale beginning farmers survive in what is a highly capital-intensive industry. Consider alone the cost of land, which is often the biggest barrier aspiring farmers face. This is particularly true for Black and Indigenous farmers, who have been systematically deprived of land, a topic that is receiving long overdue attention in Congress. Another big challenge is surviving the three-year transition period when farmers need to follow all the organic standards but cannot yet label their food as organic. Among other things, we recommend increased technical and financial assistance to help farmers transition to organic. I’m working now with a small group of people to provide detailed policy recommendations for an upscaled transition program that I hope will be announced by the new administration soon.

Q: What’s an example of the use for these numbers when it comes to benchmarking and policy success?

A: A mentor of mine, Garth Youngberg, wrote a report on organic agriculture in 1980 when he was an economist at (the U.S. Department of Agriculture) for which he was promptly and unjustifiably fired — later Garth was recognized with a McArthur Foundation Genius Award. It is one of many historic examples of USDA not supporting the organic sector. Fast forward to today, and things have not changed that much, with USDA support for organic lukewarm at best. One way we can document this is by using numbers. In our report, we establish a baseline of support that USDA should provide the organic sector — 6% of whatever dollars are being distributed. We chose this number because 6% of food purchased in the U.S. today is organic. We argue that support for the organic sector should, at minimum, be commensurate with its market share. For example, if USDA spent 6% of its annual $4 billion research budget on research directly pertinent to organic agriculture, it would amount to $240 million, which is nearly $2 million more than is currently spent. I know many of ASU’s sustainability scientists and scholars would benefit if organic research was upscaled. By using numbers, we can go USDA agency by agency and contrast the support provided to organic to overall budget allocations and demand a fair share.

Q: Of all your recommendations, is there a standout one for Arizona?

A: The majority — about 59% — of Arizona farmers and ranchers are Native American. While many Native Americans, here in Arizona and across the country, utilize production practices consistent with the USDA National Organic Program (NOP) standards, few go through the process to become certified to label and sell their products as organic. Part of the reason for this is that the USDA NOP is not well calibrated to Tribal Nation needs. After consulting with tribal leaders, including the Intertribal Agriculture Council, we came up with a few different certification pathways that we believe will work for Tribal Nations. The irony for me is that Native Americans pioneered many of the practices that organic farmers depend on and yet they are not beneficiaries in the marketplace. This has to change. Consider that in the U.S. there are almost 80,000 Native American farmers and ranchers and tens of millions of acres of farmland under tribal control. What an opportunity!

Q: Does organic farming contribute to improving the climate, a central concern alongside food security of the new ASU Julie Ann Wrigley Global Futures Laboratory?

A: Organic production uses 45% less energy than conventional agriculture, largely because organic standards prohibit use of synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. Soil-building practices required in organic, such as crop rotation, create healthier soils that absorb rainfall better, help prevent runoff and erosion, and store more water to sustain crops through drought. This fall, the Swette Center will release a report, written in partnership with Natural Resources Defense Council and Californians for Pesticide Reform, that will lay out the latest science around organic and climate, health and the economy. It has been a labor of love and we look forward to sharing it. What our report will show, however, is that while organic is part of the answer to achieving climate-smart agriculture, even organic production systems need to further evolve to secure our future. Among the 46 recommendations in the current report is that a water stewardship standard be added to the list of National Organic Program requirements. We also recommend that greater investment be made in breeds and seeds adapted for organic systems and climate change.

Q: As people go grocery shopping or visit a farmers market, what’s one thing you want them to keep in mind?

A: The No. 1 reason people buy organic food is health. We began our conversation with a number, let us close with one: 970,000,000. That is the number of pounds of pesticides applied to U.S. crops each year, nearly one-fifth of global pesticide use. Even after rinsing produce, which we should always do, some pesticides enter our bodies through residues that do not wash off. The smart — and safest — choice is organic because organic farmers are prohibited from using nearly all synthetic pesticides. Based on government data, the Environmental Working Group puts out an annual list of foods with the most concerning pesticide residues (The Dirty Dozen) and a list of foods of least concern (The Clean 15). While EWG describes organic as “the original clean food” and advocates for it, they produce these annual lists to help people on limited budgets prioritize which organic items to buy.

Top photo courtesy of iStock/Getty Images. Graphic by Alex Davis/Media Relations and Strategic Communications

More Law, journalism and politics

ASU launches nonpartisan Institute of Politics to inspire future public service leaders

Former Republican presidential nominee and Arizona native Barry Goldwater once wrote, "We have forgotten that a society progresses only to the extent that it produces leaders that are capable of…

Annual John P. Frank Memorial Lecture enters its 26th year

Dahlia Lithwick, an MSNBC analyst and senior legal correspondent at Slate, is the featured speaker at the School of Social Transformation’s 26th annual John P. Frank Memorial Lecture on…

The politics behind picking a romantic partner

A new study reveals the role that politics play when picking out a romantic partner — particularly for older adults.“Findings show that politics are highly salient in partner selection across gender…