Understanding Earth's critical zone

Arjun Heimsath, professor in Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration, teaches the course "Earth’s Critical Zone" where students explore how changes to the environment manifest themselves in landforms, water resources, soils, agriculture and ecosystems.

The Earth’s near-surface environment, known as Earth’s critical zone, supports most life on the planet. This uppermost layer that extends from the tops of trees down to several feet below the surface is the area that humans most depend on.

“We grow our food in this zone. Most of our drinking water is filtered through this zone. The wild animals, forests, deserts, mountains, lakes and rivers — all the part of the Earth’s surface that we humans engage directly with in so many ways — are all part of this zone,” said Arjun Heimsath, professor in Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

Heimsath believes that understanding the physical and chemical processes that operate in this zone, as well as the way that geology, climate and humans impact how these processes take place, is a critical step in addressing many of the challenges our planet faces.

In his course "Earth’s Critical Zone," students do exactly that by exploring how changes to the environment manifest themselves in landforms, water resources, soils, agriculture and ecosystems.

“I enjoy watching students get excited about these topics that are so important for understanding how our planet works,” he said. “I just love watching their eyes light up when they ‘get’ a new science-based concept about how some aspect of the environment that they have always taken for granted actually works. It’s such a thrill to share in their excitement.”

For Earth Day, Heimsath gave insight on the importance of understanding Earth’s critical zone and how the study of sustainability and the environment has changed over the years.

Question: You were involved in the creation of the earth and environmental studies degree at The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences — tell us about that program.

Answer: We began the earth and environmental studies degree about eight years ago, in response to the interest that a number of students in the School of Sustainability had articulated to me — to have more physical science in their degree. The hope with creating the degree was to attract students who have a fundamental interest in environmental studies along the lines of my own background — a deep commitment to understanding earth surface processes with the aim of helping to mitigate or prevent human impacts from harming the environment. … As humans continue to try to figure out how to better deal with overpopulation, climate change, biodiversity loss and habitat destruction to name a few key areas of concern, students coming out of The College with an earth and environmental studies degree will be in high demand across multiple sectors of the workforce.

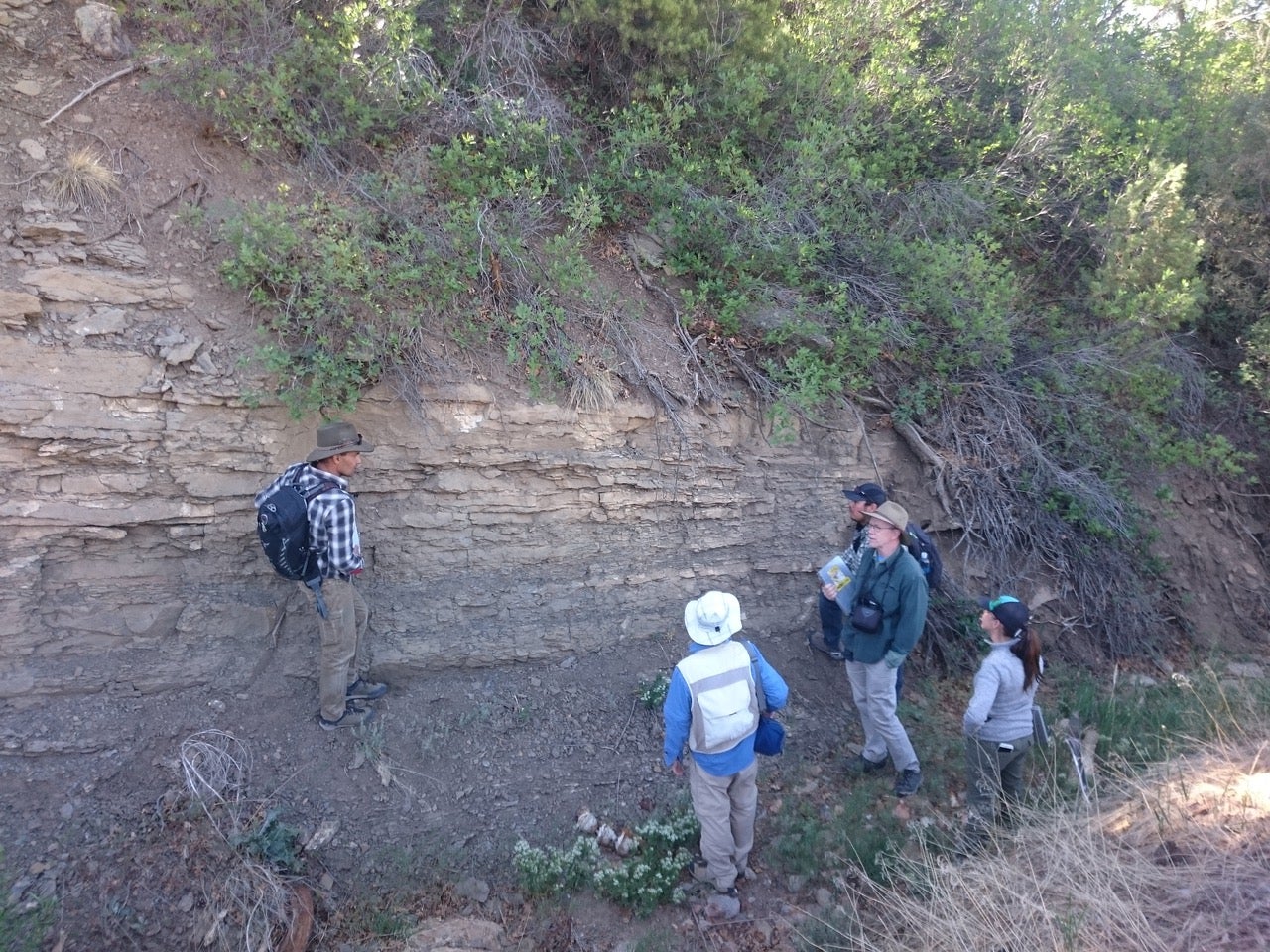

School of Earth and Space Exploration Professors Arjun Heimsath (left), Stephen Reynolds (middle) and Thomas Sharp (right) with two students at an outcrop near Durango, Colorado, while teaching in summer 2019. Photo by Nari Miller

Q: How did the "Earth’s Critical Zone" course come about?

A: I was quite active in a program at the National Science Foundation that was funding big projects focusing on the critical zone and realized that there was no single class that I had ever heard of that focused simply on Earth’s critical zone. No syllabus existed, no textbook — nothing. I thought, “How cool is this, I can make up this absolutely key class and call it ‘Earth’s Critical Zone.’” And that was that. I have subsequently gotten the class approved for science and society credit and also created a fully online, asynchronous version of it that I offer during the summer.

Q: What are some of the biggest ways you’ve seen the study of sustainability and the environment change over the years?

A: It’s become mainstream. I compare the level of awareness and education of the students that I teach in this major to those that I taught when I first started as a professor in 2000, and the difference is extraordinary. Students are coming into college as first-year students now with a level of understanding of sustainability and environmental change that seems comparable to what I emerged from my master’s degree with way back in the early 1990s. It’s encouraging and inspires hope. I’ve also noticed that college students these days seem to want to be way more proactive and engaged than my peers did 30 years ago.

Q: This Earth Month, what issues do you feel are the most crucial to address and why?

A: The same issues that have been crucial to address for the last 50 years for all the same reasons that countless environmental scientists, activists and educated politicians have been articulating over and over and over again: climate change, biodiversity loss and habitat destruction. That’s probably the most difficult aspect of this field — change is slow, and humans don’t adapt unless there’s a very rapid and obvious crisis.

The iconic sandstone landscape around Sedona, Arizona. Photo by Arjun Heimsath

Q: What can people do to effect change, and is there something that gives you hope for the future of these issues?

A: That trite expression that has maybe fallen out of the limelight is certainly applicable here: Think globally, act locally. This begins by voting in the right people to formulate science- and truth-based policies and continues by getting involved working on local issues at whatever level one is able to give. I feel hope because I’ve watched human behavior change to be more environmentally aware and also because I strongly believe the younger generations are way ahead of their elders in terms of changing behavior toward more environmentally friendly practices. There’s so much good that can be done, and I like seeing the younger generations getting into it.

To learn more about Earth Month at ASU, visit earthmonth.asu.edu.

More Science and technology

ASU researchers engineer product that minimizes pavement damage in extreme weather

Arizona State University researchers have developed a product that prevents asphalt from softening in extreme heat and becoming…

New study finds the American dream is dying in big cities

Cities have long been celebrated as places of economic growth and social mobility, but new research suggests that their role in…

Ancient sea creatures offer fresh insights into cancer

Sponges are among the oldest animals on Earth, dating back at least 600 million years. Comprising thousands of species, some with…