Seeding knowledge for biodiversity

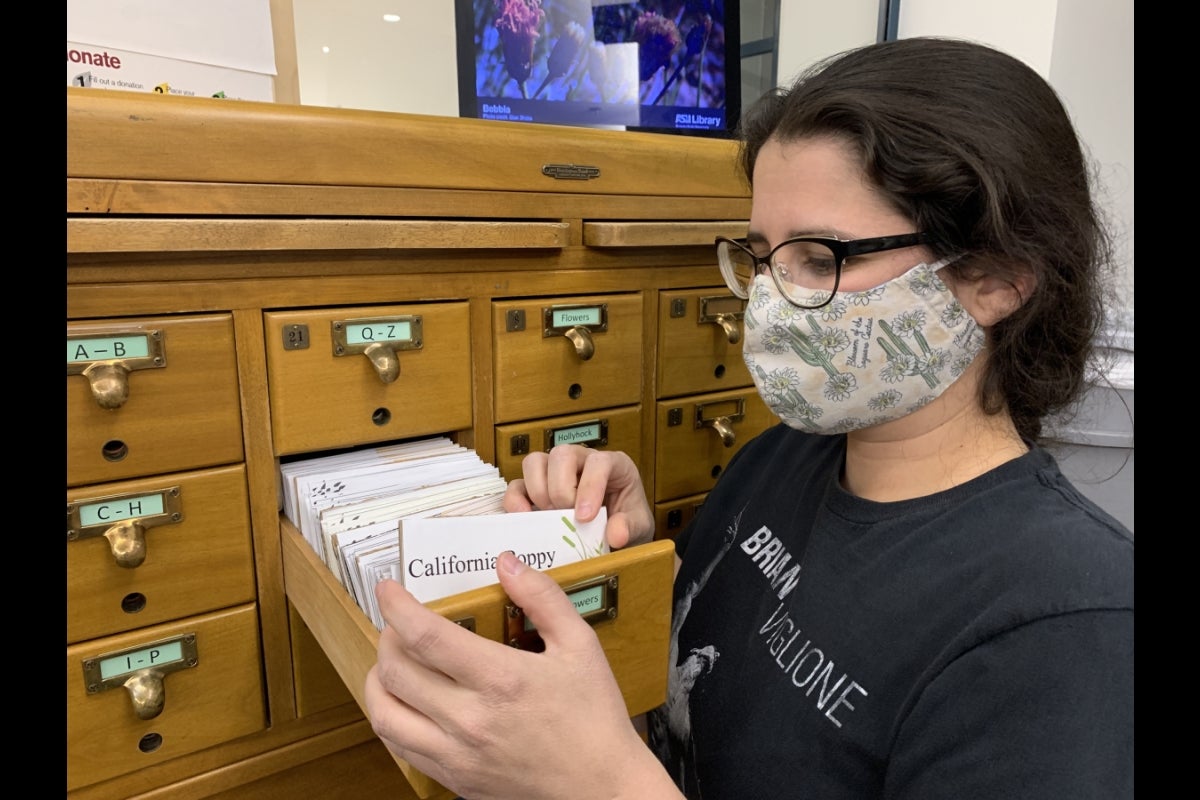

Christina Sullivan, a library specialist, manages the seed library in the Design and Arts Library on the Tempe campus. Photo by Marina Ioffe

Is there anything more experimental than a seed?

Planting something in the ground and seeing what grows there?

The practice of experimentation with a focus on native plants is helping to grow the daily give-and-take activities of the seed library at Arizona State University, situated in the Salt River Valley on the homelands of Indigenous peoples.

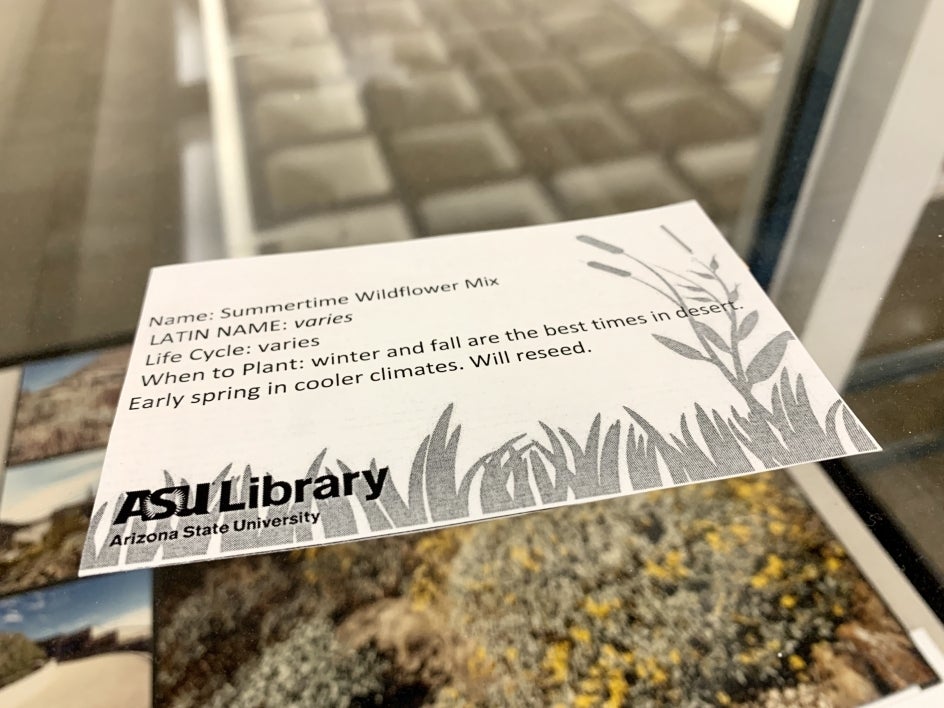

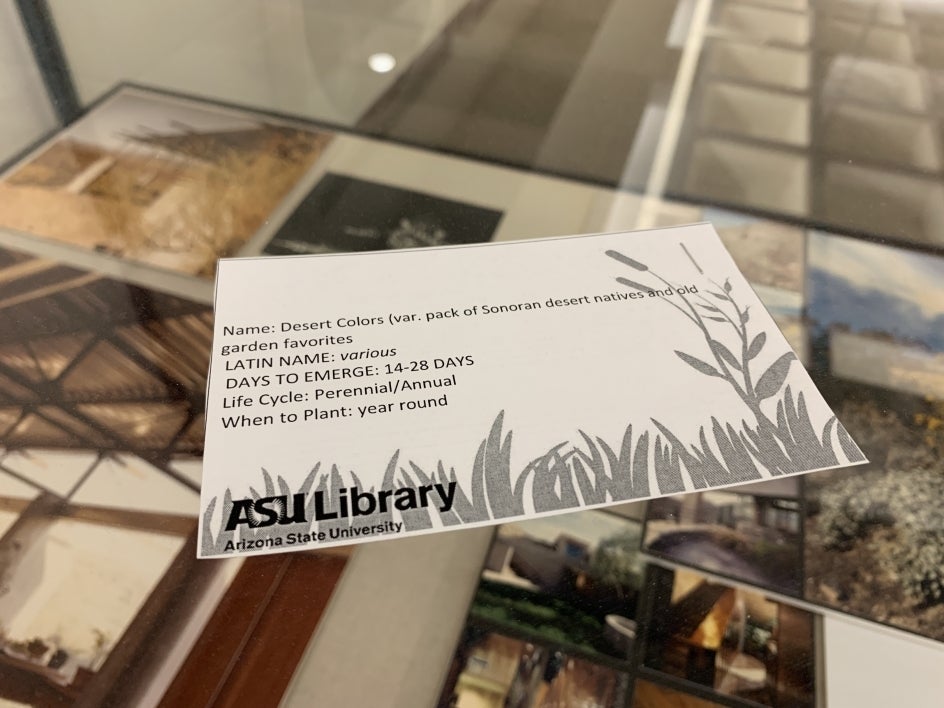

Tending to a repurposed card catalog of edible plant and herb seeds, curated specially for the Arizona climate, is the work of Christina Sullivan, a library specialist who manages the seed library in addition to NatureMaker, a joint collection of the ASU Library and the Biomimicry Center. Both are housed in the Design and Arts Library on the Tempe campus.

Sullivan’s role keeps her attuned to the seasons and cycles of what grows here.

“Seeds are inexpensive and give people an opportunity to experiment with their gardens — seeing what works and what doesn’t,” she said. “The seed library is really good at teaching people about what can grow in Arizona, specifically.”

For example, there’s a difference between drought-resistant plants, such as aloe, and native plants belonging to our Sonoran Desert ecosystem, which is home to the ocotillo, the brittlebush and the saguaro cactus.

“The Sonoran Desert is pretty diverse and specialized,” said Sullivan, who has grown up in Arizona observing desert diversity on hiking trails, state highways and in her own backyard. “A saguaro cactus only grows in the Sonoran Desert, so there are rules and regulations for how to care for that cactus or how to remove it. Right now, we have people coming in from other places not knowing about this place and they begin remodeling old houses that come with native plants. Sometimes they end up cutting down a saguaro because they either don’t want to go through the trouble or there’s not an understanding that the saguaros are protected.”

Their protection is, of course, highly consequential to both animals and people that depend on the saguaro’s provision of a home and food for birds, insects, reptiles, bats and other mammals.

Sullivan’s encouragement of native plant growth aligns well with a new citizen science project throughout April that invites the ASU community and the entire state of Arizona to document flowering plants and pollinators on ASU’s campuses.

Citizen science is a collaborative process among scientists and the general public to speed up the collection of data by scaling up the number of informed data collectors and the tools and resources to which they have access, making libraries key facilitators.

This year’s project, rooted at the intersection of Earth Month and Citizen Science Month, was jointly developed by the Center for Biodiversity Outcomes and the School for the Future of Innovation in Society with support from SciStarter, a popular online platform for citizen science projects founded by Darlene Cavalier, a professor of practice at the school.

“The idea to focus on pollinators and flowering plants grew out of our interest in recording and understanding the biodiversity present on ASU’s campuses,” said Alice Letcher, a project manager for the Center for Biodiversity Outcomes. “The data collected by citizen scientists will help us document the distribution of pollinators and flowering plants on ASU’s Phoenix-area campuses. In addition, the experience of developing a project for citizen scientists will help us understand how we can effectively engage the public.”

Developed by Jared Clements, an undergraduate student majoring in biology, the project will assist the biodiversity research of Gwen Iacona, an assistant research professor in the School of Life Sciences, within The College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

There are three questions that citizen scientists will help them to answer:

- How do pollinator species density (the number of individuals of a given species in an area) and species diversity (the number of different species present in an area) vary with location?

- How do pollinator species density and species diversity vary with the type of flowering plants present? (“Type” means whether a plant is native or non-native.)

- How do data collected for this project by citizen scientists compare to data collected for this project by professional scientists?

“We’re interested in what differences we can observe in how the two groups collect data,” said Letcher.

Several local public libraries around Phoenix and the East Valley are providing citizen science kits for those wanting to participate. The kits contain things like “field guides, magnifying lenses and other materials to make the data collection experience more robust,” Cavalier said.

A limited number of citizen science kits for homeschoolers are available at Fletcher Library on ASU’s West campus. The outreach effort is being led by Carolyn Starr, the outreach coordinator for the New College of Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences.

Get information and register for the project, which is open to all ages and levels of experience.

“Citizen Science Month provides a wonderful opportunity to fill research data gaps around campus,” said Cavalier, “while engaging people in simple but important ways.”

More Science and technology

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that…

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your…