Imaginary animal battles advance science communication

Artwork created for #2021MMM. Common Treeshrew, Tupaia glis, by Charon Henning.

In a battle between a boar and a bobcat, who would win? What about between a group of Neandertals and a giant short-faced bear?

Thousands of students across the world have found out those answers and more through March Mammal Madness, a fictional tournament powered by science, social media and imagination. Now the creators, including Arizona State University professors, explain why the mammal battles have become so popular and how they hope to inspire other scientists.

Modeled after NCAA March Madness in basketball, March Mammal Madness is an annual tournament featuring 64 animals that battle fictitiously in rounds until there is one champion. While the actual fights are not real, the battles are suspensefully described “live” on Twitter with play-by-play descriptions of the action. The outcomes rely on published research about the animals’ adaptations, behaviors and environment.

This year's tournament begins Monday, March 8.

In just six years, the popularity of March Mammal Madness grew to more than 250,000 players in 2019.

Katie Hinde founded March Mammal Madness in 2013. She is an anthropologist and associate professor at Arizona State University’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change. Hinde, who now works on the tournament with a team of more than 30 scientists, artists and other professionals, recently published an academic paper exploring the success of March Mammal Madness as “performance science.”

Storytelling is key

The findings emphasize that the captivating story of an animal’s journey through the tournament is crucial to communicating about science in a fun and engaging way.

Psychologically, humans are wired to learn information by passing down stories through generations. Hinde notes how people have been telling stories to instill knowledge about nature and cultural values for tens of thousands of years.

The animals become characters in the MMM story as they advance through the bracket. Previous battle wounds, for example, may hinder their future ability to fight. In one 2019 battle, carnivores had eaten too much after winning a fight the day before, so they “forfeited the battle” because they were not interested in a predatory hunt. The narrators shared research about gut passage time and carnivore behavior.

Adding to the storytelling component, the animals battle in detailed, real settings, allowing people to imagine what it’s like there. For example, a battle between a hyena and a coyote took place in Harar, Ethiopia at dusk. They crossed paths at a local dump, where they were both scavenging for food.

The science behind MMM also draws on findings from human evolution and sociocultural anthropology, including the power of collective storytelling and shared experiences. As participants talk about previous years’ tournaments, they’re creating a shared oral history that can be re-lived and remembered.

“It was really fun to delve into why narrative is powerful for the human mind,” Hinde said. “We know that narrative has been brought into lots of educational spaces, like social studies, history and language arts, but it really hasn’t been adopted in the same way with STEM.”

Who would win?

The tournament’s success also relies on gamification, meaning participants feel like they are playing a game. The tournament has been widely adopted in classrooms, providing educators an interactive way to teach about natural history, ecology and biology.

Asking high school students to research mammals and learn facts about them would likely be seen as busywork, but asking students to guess who would win in a fight between two animals becomes more interesting. Hinde’s paper explains that the addition of both imagination and competition allows students to become active constructors of knowledge.

Linda Correll, an instructional supervisor and former high school teacher located in Virginia, has used MMM in her classroom. She assigned each student an animal to research.

“There was a lot of talk about how ‘mine is going to beat yours’ or ‘this one is going to make it to the championship,’” Correll said. “Upsets are really fun, especially when the animal that wins has been classified as ‘too weak’ or ‘not strong enough’ by most students. Someone usually gets really fired up as they try to explain to everyone how the outcome was totally impossible.”

Some educators print brackets and display them in school hallways, while others have “Beat the Teacher” competitions.

The tournament also features detailed illustrations of the animals, integrating art and science. Prior studies have shown this narrative and visual combination helps students retain information and creates more enthusiasm for science.

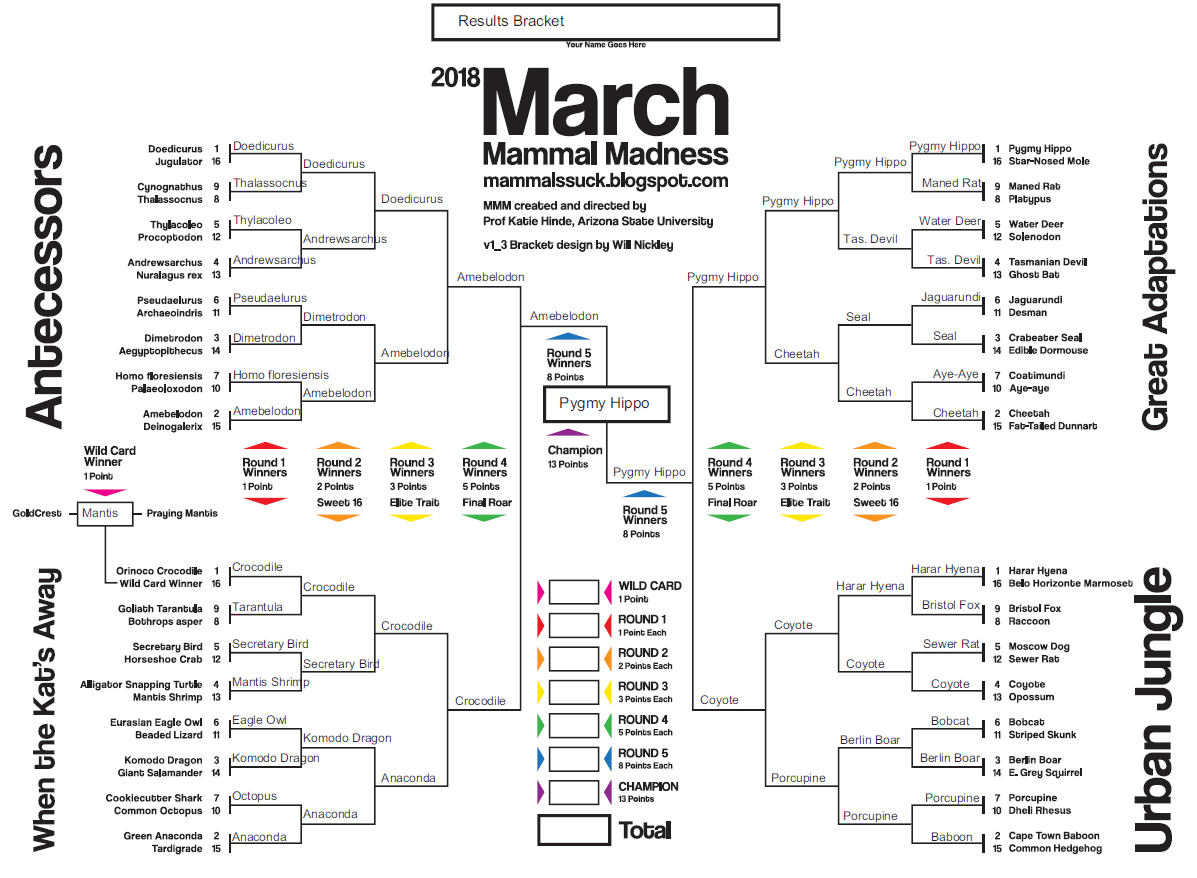

The 2018 March Mammal Madness results. Reprinted with permission from Hinde et al., eLife, doi.org/10.7554/eLife.65066, (2021). The article is published open access via a CC-BY license.

Balancing education and entertainment

This creative and fun approach to science communication isn’t perfect. March Mammal Madness balances education and entertainment, and sometimes fans question the plausibility of battle outcomes. Hinde said some fans were not pleased when a “Mythical Mammals” division appeared in 2015, but the MMM team was able to spark dialogue about how humans often create mythical animals with exaggerated or recombined features of real animals in their environment.

Overall, the growth of the tournament, particularly in classrooms, speaks to the effectiveness of this interactive approach to science.

Beyond the tournament dates in March, the energy and enthusiasm carries throughout the year. There are pre-event contestant reveals, post-event celebrations and off-season movie nights, and fans can purchase artwork from the tournament online. An elementary school student had an MMM-themed birthday party, and one fan even got a tattoo related to the tournament.

“All in all, this has been the great honor of my career,” Hinde said. “To have collaborated on creating something that is used by so many, loved by so many, and gets people excited to learn about the most precious parts of our natural world.”

The authors of the paper hope their findings inspire other science communicators to share their innovative projects and successes, and ultimately help more people see that science can be fun.

Walking the walk, the paper showcases creativity and enthusiasm in a way that is not common in many scientific research papers. The published findings include humor and puns alongside approved research studies and source citations.

What to expect for #2021MMM

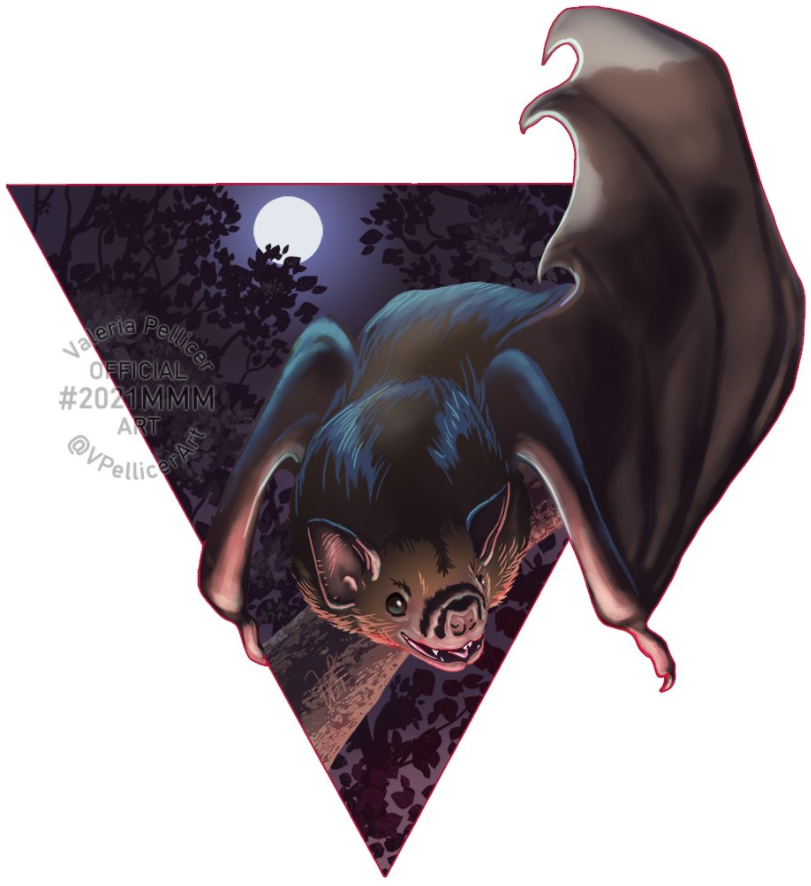

Artwork created for #2021MMM. White Winged Vampire Bat, by Valeria Pellicer.

This year, perhaps as a nod to the mythical creature debate of 2015, half of the contestants are named after myths. Unlike last time, these animals are real. They each have a name derived from a myth, like the white winged vampire bat and the black dragonfish.

The battle narrators know a lot about the animals, so people filling out brackets will need to bring their A-game. Hinde said beyond researching the physical and behavioral traits of the animals, she also checks seasonal and environmental conditions like weather, mating habits and even tide tables.

For example, some fans were likely surprised in 2019 upon finding out that the bull moose did not have his antlers to use in battle. Moose shed their antlers at the end of winter and regrow a new set every year.

For more information about 2021 March Mammal Madness or to download a bracket, visit ASU’s March Mammal Madness Library Guide.

The battles will be live-tweeted on @2021mmmletsgo and #2021MMM beginning on Monday, March 8.

“March Mammal Madness and the power of narrative in science outreach” published last week on eLife.

More Science and technology

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that…

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your…