More than 3,000 animal species in the world today are considered endangered, with hundreds more categorized as vulnerable. Currently, ecologists don’t have reliable tools to predict when a species may become at risk.

A new paper published in Nature Ecology and Evolution, “Management implications of long transients in ecological systems,” focuses on the transient nature of species and ecosystem stability and illustrates how management practices can be adjusted to better prepare for possible system flips. Some helpful modeling approaches are also offered, including one tool that may help identify potentially endangered populations.

Ying-Cheng Lai, a professor of electrical engineering and physics at Arizona State University, focused on the mathematical modeling process of the research.

“The Mexican gray wolf is an example of an endangered species that is experiencing a population resurgence in some areas, yet remains vulnerable in others,” Lai said. “The predator-prey relationship between the Mexican gray wolf and elk, mule, white-tailed deer, pronghorn, javelina, rabbits and other small mammals is an example of how interspecies relationships can affect endangerment. In a general predator-prey relationship, a significant reduction in the prey population can make the predator endangered.

“These kinds of interactions, plus other factors such as the species decay rate, migration, the capacity of the habitat, and random disturbances, are included in the mathematical prediction model,” Lai continued, “and it turns out that, more common than usually thought, the system evolution dynamics can just be transient. Transients in ecosystems can be good or bad, and we want to develop control strategies to sustain the good ones and eliminate the bad ones.”

Risks that go undetected until the species is already shifting from stable to vulnerable present the greatest challenges.

“A species or an ecosystem may seem perfectly stable when it unpredictably becomes vulnerable, even in the absence of an obvious stressor,” said Tessa Francis, lead ecosystem ecologist at the Puget Sound Institute, University of Washington Tacoma, managing director of the Ocean Modeling Forum, University of Washington, and lead author of the paper. “In some cases, modeling interactions between species or ecosystem dynamics can help managers identify potential corrective actions to take before the species or system collapses.”

Alan Hastings, a theoretical ecologist at University of California, Davis and an external faculty member at the Santa Fe Institute, notes that, “as we apply these mathematical models to understanding systems on realistic, ecologic time scales, we unveil new approaches and ideas for adaptive management.

“The goal is to develop management strategies to both extend positive ecosystems as long as possible and to design recovery systems to support resurgence from vulnerable states,” Hastings said. “Over time, as successful predictions are incorporated into the mathematical model, the tool will become more accurate.”

But mathematical models are not a panacea, cautions Francis.

“While models can be useful in playing out ‘what ifs’ and understanding hypothetical consequences of management interventions, just as important is changing the way we view ecosystems and admitting that things are often less stable than they appear.”

Additional contributors to the research include: Karen C. Abbott, Case Western Reserve University; Kim Cuddington, University of Waterloo; Gabriel Gellner, University of Guelph; Andrew Morozov, University of Leicester, Russian Academy of Sciences; Sergei Petrovskii, University of Leicester; and Mary Lou Zeeman, Bowdoin College.

The team, with sponsorship from the National Institute for Mathematical and Biological Synthesis (NIMBioS) through the University of Tennessee, has been working together as a study group named “NIMBioS Working Group: Long Transients and Ecological Forecasting.” The group has produced a number of papers focused on developing mathematical models to understand long transients in ecosystems.

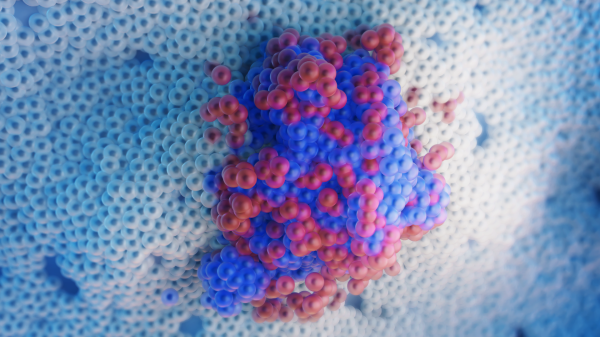

Top image: New research can help ecosystem managers identify species vulnerabilities and prevent populations from becoming at risk, like the endangered Mexican gray wolf. Photo courtesy adogslifephoto.

More Science and technology

ASU and Deca Technologies selected to lead $100M SHIELD USA project to strengthen U.S. semiconductor packaging capabilities

The National Institute of Standards and Technology — part of the U.S. Department of Commerce — announced today that it plans to award as much as $100 million to Arizona State University and Deca…

From food crops to cancer clinics: Lessons in extermination resistance

Just as crop-devouring insects evolve to resist pesticides, cancer cells can increase their lethality by developing resistance to treatment. In fact, most deaths from cancer are caused by the…

ASU professor wins NIH Director’s New Innovator Award for research linking gene function to brain structure

Life experiences alter us in many ways, including how we act and our mental and physical health. What we go through can even change how our genes work, how the instructions coded into our DNA are…