Desert ecologists have a hard job. Their efforts to understand the workings of the natural world have never been more urgent. Dryland ecosystems support over a third of the world’s people and food, but they are getting hotter and drier. In 2020, Arizona broke its record for most days at or above 110 degrees. Yet the research needed to protect these ecosytems is a complicated business that involves arduous, sometimes even dangerous fieldwork and a great amount of precious time.

Arizona State University students and researchers are discovering that innovations in engineering and computer science can offer intriguing solutions to boost ecologists’ efficiency and help them find actionable environmental insights sooner.

Heather Throop, an associate professor of ecology in ASU’s School of Earth and Space Exploration and School of Life Sciences, studies carbon and nitrogen cycles in dryland ecosystems. Jnaneshwar Das, an assistant research professor in the School of Earth and Space Exploration and the Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science, creates drones and robots that can collect sophisticated environmental data.

“A unique aspect of ASU is the really collaborative nature of this university.” — Associate Professor Heather Throop

Throop first met Das when he gave a presentation on using imaging technology and machine learning to monitor and count crops in agricultural settings. She saw right away that working together would open up unique opportunities for research.

“I recognized that those same kinds of processes could be useful for the kinds of work that I do. I was really excited to talk with him,” Throop said. “A unique aspect of ASU is the really collaborative nature of this university.”

Their discussions led to the formation of an ecological robotics group. Led by Throop and Das, it includes ecology and geology students, postdoctoral researchers and engineering students from Das’ Distributed Robotic Exploration and Mapping Systems (DREAMS) Lab and Throop’s Drylands in a Changing Earth Lab. Together, the group is coming up with creative ways to study dryland ecosystems.

Associate Professor Heather Throop and research technician Nicole Hornslein collect plant litter samples in the Sonoran Desert. Photo (taken before COVID-19) courtesy of Jnaneshwar Das.

Solutions to scale up science

According to the United Nations, drylands take up over 40% of Earth’s land surface, are home to one-third of the world’s population and produce over 40% of global agriculture, making these systems and their carbon cycles important to understand.

Studying the carbon cycle in drylands is challenging because most of the carbon is stored belowground in the form of roots, unlike wetter systems where most of the carbon is used to grow stems and canopies aboveground.

“Having a better understanding of these biological processes allows us to better manage these systems now and for the future,” Throop said.

To survey plant life at a small scale, ecologists typically comb the landscape systematically. It’s a laborious, slow-moving process that takes them away from manicured trails and into the rougher, less friendly brush. In addition, the data collected by multiple people can be inconsistent.

“We want to do things at scale so that we humans don't have to do mundane tasks over and over or be put at risk of hazards,” said Das.

To that end, the DREAMS Lab offers ecologists the ability to utilize technology like drones, high-tech cameras, data analysis and AI programs. Drones provide a way to look at a much broader area in much less time. And unlike humans, drones can collect data with perfect consistency throughout their time in the field.

However, Das and Throop aren’t aiming to replace researchers with technology. Rather, they see them as complementing one another.

“We need data from researchers to know how to interpret our drone-collected information. The technology will allow us to expand our knowledge, but it will have to build upon a foundation of ground research by humans who understand the system,” Throop said.

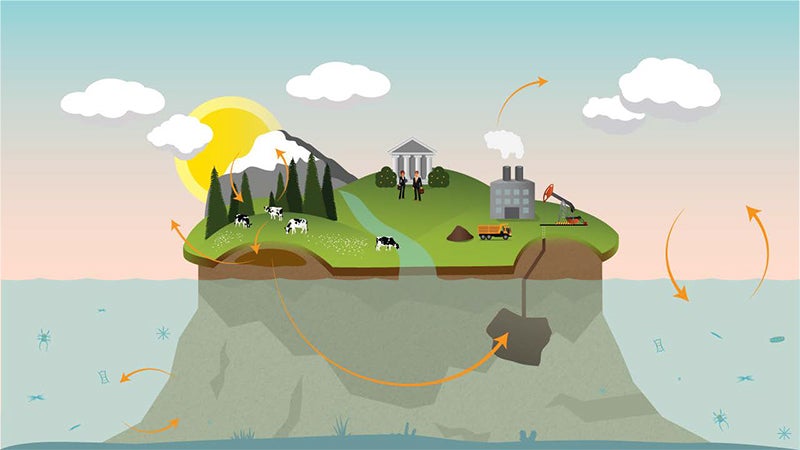

Carbon moves through the atmosphere, biosphere and lithosphere in various forms, in a process known as the carbon cycle. Illustration by Jessica Flanagan.

Turning over an old leaf

The carbon cycle is a biogeochemical process that shuffles carbon around the ecosystem, moving through living organisms, water, soil and the atmosphere. Plants, as an important part of that cycle, take carbon from the atmosphere and store it in the form of wood, leaves and roots. When their leaves fall, they return carbon and other nutrients back into the cycle.

But where does that material end up? In a forest with dense plant life and regular rain, the leaves might just remain where they fall and slowly rot there. But the desert is different. Patches of brush are surrounded by bare earth, so wind and flash floods can easily shift leaves around on the ground’s surface.

“Where dead material accumulates influences where organisms that feed on it might be, what nutrients are available to plants and how water is retained in the system. There are really big implications for where that ends up,” Throop said.

But figuring out how and where the leaves break down is like following a vanishing trail — as the leaves decompose, they disappear, taking their secrets with them. Alejandro Cueva, a postdoctoral researcher in the School of Earth and Space Exploration, is studying areas of the desert landscape that retain plant litter.

There are basically three types of ground in a desert, he says: bare and exposed; covered with grass; and beneath a canopy. Each has its own microclimate with unique characteristics like moisture, temperature and solar radiation that affect how litter decomposes.

Traditional methods of observation use images of the landscape from satellites or airplanes, meaning they miss information under trees, shrubs and rocks. Cueva is working with Das on a way to take photos nearer to the ground with a GoPro or cellphone camera, feed those images into a computer program and teach the program to tell the difference between trees, bare soil, rocks or piles of leaf litter. They’re also teaching the program to detect how much litter is present, and ultimately, how much it weighs.

“We can calculate the volume of leaf litter on the computer. That’s fantastic — now, how can we calibrate that to having a weight? I am interested in the weight, not in the volume, because litter can have different densities,” Cueva said.

Creating such technology is a challenging task, but it has a hefty payoff: Once complete, their program and methods will allow Cueva and other ecologists to scale up their data collection without needing to spend years in the field.

Throwing some shade at desert cities

Luiza Teophilo Aparecido, a postdoctoral researcher and Exploration Fellow in the School of Earth and Space Exploration, is taking an ecological approach in her quest to mitigate urban heat islands. In cities like Phoenix, human activities and structures make the metro area warmer than surrounding rural areas, creating an “island” of heat.

“I want to assess how different tree species can help with cooling the environment, not just through the type of shade that they can provide, but also through transpiration,” Teophilo Aparecido said, referring to the way plants release water vapor that cools their surroundings.

Many factors influence what kinds of trees we put in our cities — but not always the right ones.

“In urban settings, we tend to select trees to plant based on being pretty or cheap, but not often on the characteristics that are really going to impact us physically in the long term,” Throop said.

There are also plants that only solve the problem halfway, says Teophilo Aparecido. One tree might give copious shade but also require tons of water, while another may need less water but provide scanty shade. An ideal tree species for fighting urban heat — and benefitting city residents — would strike a balance between cooling ability and water use.

“We can put a number on shading and cooling, and then, looking at how much water trees are consuming and how healthy they are in general, we can recommend what desert cities like Phoenix should plant,” Das said.

“We're trying to make plant ecology practical for the people here in Phoenix and other places that are affected by urban heat island effects,” Teophilo Aparecido added.

The challenging part of her project is that she needs to study sparse individual trees. Typical plant ecology surveys use imagery from satellites, planes or LIDAR, which aren’t at a fine enough scale for her purposes.

Teophilo Aparecido is working with the DREAMS Lab engineers to record multispectral and 3D images of trees. A map of a tree’s canopy can tell her how much shade the tree can provide, how much light its leaves reflect and how much heat it’s absorbing or dissipating. She also wants to be able to predict how a tree’s shade changes throughout the day and, in collaboration with Desert Botanical Garden ecophysiologist Kevin Hultine, to measure how urban trees respond to heat.

“It's ambitious. I think there's a reason why people haven't been doing it yet,” she said. “Trying to explore ways to implement innovative technology to gather this data makes our lives a little easier and also makes it easier for people in the future to do this type of work. I think as early career scientists that care about the health of urban systems, that's a smart move on our part.”

Graduate student Edauri Navarro-Pérez submerges plant roots in water and collects images with a GoPro camera. A computer algorithm will take the images and recreate the root structure in 3D. Photo courtesy of Jnaneshwar Das.

The root issue

Edauri Navarro-Pérez, an environmental life sciences doctoral student in the School of Life Sciences, looks at plants not from aboveground, but below. She wants to understand how different root traits can affect the desert soil.

“These roots' properties can alter the carbon cycle of the soil and they can alter the soil’s texture and water properties. But it has not been well looked at in dryland ecosystems,” she said.

As the literal foundation of the ecosystem, soil is a crucial starting point in restoring a landscape. Navarro-Pérez sees the roots of plants as one of the first points of access to the soil, and thus an important tool in maintaining its health.

“In dry systems like here in Arizona… really, the forest is belowground.” — Associate Professor Heather Throop

“We have this bias because we see the aboveground parts of plants, and that's only a small fraction, particularly in dry systems like here in Arizona, where really, the forest is belowground,” Throop said.

The intricate, underground nature of roots makes them difficult to study. Understanding them begins with a better way to record their structure.

“The question we are asking is, how do you map a root in 3D?” said Das.

Working with the engineers, Navarro-Pérez takes photos or videos of the roots from multiple angles and feeds them into a computer program that generates a 3D image.

Once her plants of interest have had time to grow in their pots, she samples the surrounding soil to analyze its properties before removing the plant so she can map the root structure.

In order to get a clearer picture of the roots without them getting tangled up, she photographs them from underwater in a pool, where the roots can suspend and spread out.

Harish Anand (left) and Zhiang Chen, both graduate students at the time, calibrate a multirotor drone at the 2019 Student Cyber-Physical Systems Challenge, an annual competition co-organized by Das that gives students the chance to apply AI and robotics to ecological questions. Photo courtesy of Jnaneshwar Das.

The artificial thought that counts

One research specialist in the DREAMS Lab, Harish Anand, is hard at work on a software tool that powers several of the group’s other projects.

This geographic information system, called DeepGIS, uses AI to help researchers count objects of interest that appear in a given image. Those include recording such varied subjects as moon craters, coral reef species, fruit, rocks and desert wildlife — all tested and used by various members of the group.

To use the DeepGIS tool, Anand or another researcher first has to teach the AI what to look for. He does this by circling the target he wants it to count, like a crater, which makes an annotation. The researcher has to use a variety of images to make the AI effective.

Training usually takes around eight hours, after which the tool can begin predicting data. However, Anand stresses that the learning process is never truly finished. Researchers can continue to refine the tool’s abilities by making more annotations.

“That's what we have been calling the annotation game, constant input between AI and experts,” Das said. “And this game shouldn't end, because nature is always changing.”

At rock bottom

One of the projects that uses DeepGIS is a collaborative effort between an undergraduate geology major, Catherine Collins, and an exploration systems design doctoral student, Zhiang Chen.

Collins studies a special kind of bacteria that lives on the underside of hypoliths, a type of rock found in the Namib Desert of southern Africa and other arid environments such as the Sonoran Desert.

“These are quartz rocks that allow enough light through where cyanobacterial colonies can grow on the bottom, and they photosynthesize, so they can become a carbon sink,” she said.

These bacteria that use the sunlight to make food, just like plants, are important in places like the Namib Desert, where vegetation is scarce. The microorganisms are a key pathway for carbon to be absorbed from the atmosphere.

“Arid environments encompass a really huge percentage the world’s ecosystems, so this is an important chunk of the global carbon cycle to pay attention to,” Collins said.

Ecologists have documented large hypoliths, but have potentially missed a huge number of small ones that are harder to see and count.

“I've done my own studies in the Namib where we look at hypoliths, and one thing that we've found is there’s a lot of bias,” Throop said. “We go for those big rocks because they're more interesting, but what Collins is finding is that there's way, way more of these small rocks that haven’t been studied. So there's the potential that we're missing all these organisms that are doing important biological processes underneath these smaller rocks.”

Chen was working on training a DeepGIS program to detect the size, shape and positions of rocks in a fault scarp when he learned of Collins’ project and pivoted to help.

“We realized that this program we developed can also be used in other domains. So we use the same program for hypolith detection,” he said.

Collins analyzes images of Namib Desert gravel by hand, making annotations of quartz rocks that have the potential to harbor hypoliths. Chen uses those annotations to teach the AI to detect potential hypoliths in the photo and record their sizes.

Both of them put the resulting data into charts that give Collins an idea of how much cyanobacteria could be present. By comparing their charts, Chen can test the AI’s accuracy and refine it for future use.

“We need a lot of data,” Chen said. “If we do this manually, you can imagine how time consuming that will be. But if we use AI, then it will be very efficient.”

At the Volcanic Tablelands in Bishop, California, School of Earth and Space Exploration graduate researchers Devin Keating (left) and Zhiang Chen configure a drone before using it to collect data on a rocky fault scarp. AI algorithms use such data to map plants, rocks and plant litter. The nearby guitar and drum are there to keep things light and reduce stress — for instance, says Das, if a drone crashes, they can take a quick music break before they start fixing it. Photo (taken before COVID-19) courtesy of Jnaneshwar Das.

Doing some soil searching

Wildfires are a phenomenon that Arizonans are all too familiar with. But, beyond their immediate effect of burning up trees and shrubs, they also change the soil. Combined, this makes it much easier for the soil to wash away.

Devin Keating, a geology master’s degree student in the School of Earth and Space Exploration, is working to determine how vulnerable a landscape is to a debris flow after experiencing a wildfire.

“Debris flows are catastrophic events. It's basically a wall of liquid concrete.” — Geology master’s degree student Devin Keating

“Debris flows are catastrophic events. It's basically a wall of liquid concrete,” he said. These extremely dense flows scrape the land down and can even remove houses.

“They're very powerful, but they start with very tiny beginnings at the very top of the mountain. There are these little centimeter-scale features called rills where rainwater starts collecting. And that's where everything starts snowballing and building out of control,” he said.

Being able to spot minuscule features like these, as well as monitor hill slope and changes to the number of rocks and trees, can help officials determine more quickly if an area is hazardous.

“People are doing stuff like this, but nobody's doing it very rapidly,” Keating said. The U.S. Forest Service and the U.S. Geological Survey have different methods for monitoring the landscape, which don’t perfectly overlap. And they rely on images from satellites or planes, which usually don’t have a resolution fine enough to spot these small but crucial features.

“The machine learning algorithm could let us get this done very quickly so we can put out hazard maps as soon as possible, instead of months later,” he said.

Keating uses drones to collect images of a site and creates a 3D map of the landscape. Mapping a site multiple times over a longer period allows him to measure how features change in 3D, like how much a shrub grew or a hill flattened. And knowing how vegetation, earth and rocks have shifted and changed can indicate how resistant or vulnerable the area is to erosion.

“Recognizing these little tiny things that would take forever to count is where the machine learning comes in,” he said. “Once the algorithm is trained, it runs really quickly. You could fly a drone over an area that recently burned and very rapidly establish some risk values.”

The DREAMS Lab autonomous boat, named "Robo-boat-o," sets sail for a test run at a local lake in Tempe. Photo courtesy of Jnaneshwar Das.

You’re gonna need a small boat

Not content to limit themselves to the air above and the soil below, the group has also developed a drone that can roam the water. Sarah Bearman, an exploration systems design doctoral student, is studying the water quality of Tempe Town Lake with a small, self-driving boat.

The Central Arizona Phoenix Long-Term Ecological Research project, known as CAP LTER, has an instrument called a data sonde that stays in one place in the lake and transmits information about the water surrounding it.

“What we want to do is use this autonomous boat to get spatial data to kind of compare and see, are the processes we are seeing in the lake at this one spot reflective of the processes that are going on throughout the entire lake?” Bearman said.

When she sends the boat out, it will stop periodically as it wanders around the lake and take samples from different areas with a sensor that lowers from the boat.

In the future, researchers could deploy this device in a natural lake (Tempe Town Lake is human-made) to get an idea of how much carbon enters a lake in the desert and how that carbon then cycles through.

A DREAMS Lab drone flies at the Volcanic Tablelands in Bishop, California. It’s equipped with a multispectral camera, which helps it differentiate between living plants, dead plants and nonplant matter. Such technology helps ecologists find quicker answers. Photo courtesy of Jnaneshwar Das.

Faster science for a secure future

Solving environmental riddles like these is more pressing now than ever before. Effective carbon cycle management, resilient landscapes and cooling urban vegetation could help Arizona have less record-breaking summers in the future. And as human livelihoods increasingly rely on dryland ecosystems, understanding them will help desert dwellers manage the land sustainably.

By matching elusive ecological questions with innovative engineering methods, Throop and Das’s group can meet these urgent needs with faster, more efficient research — and hopefully fresh solutions as well.

“The problems are intriguing. It all starts with conversations, then the engineers show the ecologists some examples of what we can do. It has always quickly led to some interesting collaborations,” said Das.

“I think it’s really exciting to have this interdisciplinary research group where we're asking ecological science questions, but then working with the expertise of Das and his group to help us with cutting edge engineering and AI approaches. That really strengthens our science,” said Throop.

Top photo: Brushing the dust from a previous flight off one drone in his lab, Das explains that increasing these environmental robots’ endurance for longer flights and improving their awareness of where they are in their surroundings are continual challenges. Photo (taken before COVID-19) by Andy DeLisle/ASU

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…