ASU student contributes to global dire wolf DNA research

Photo by Marcel Langthim, courtesy of Pixabay.

An Arizona State University anthropology student is among a group of international researchers who this week published one of the first DNA studies of dire wolves — extinct canines that roamed Earth thousands of years ago.

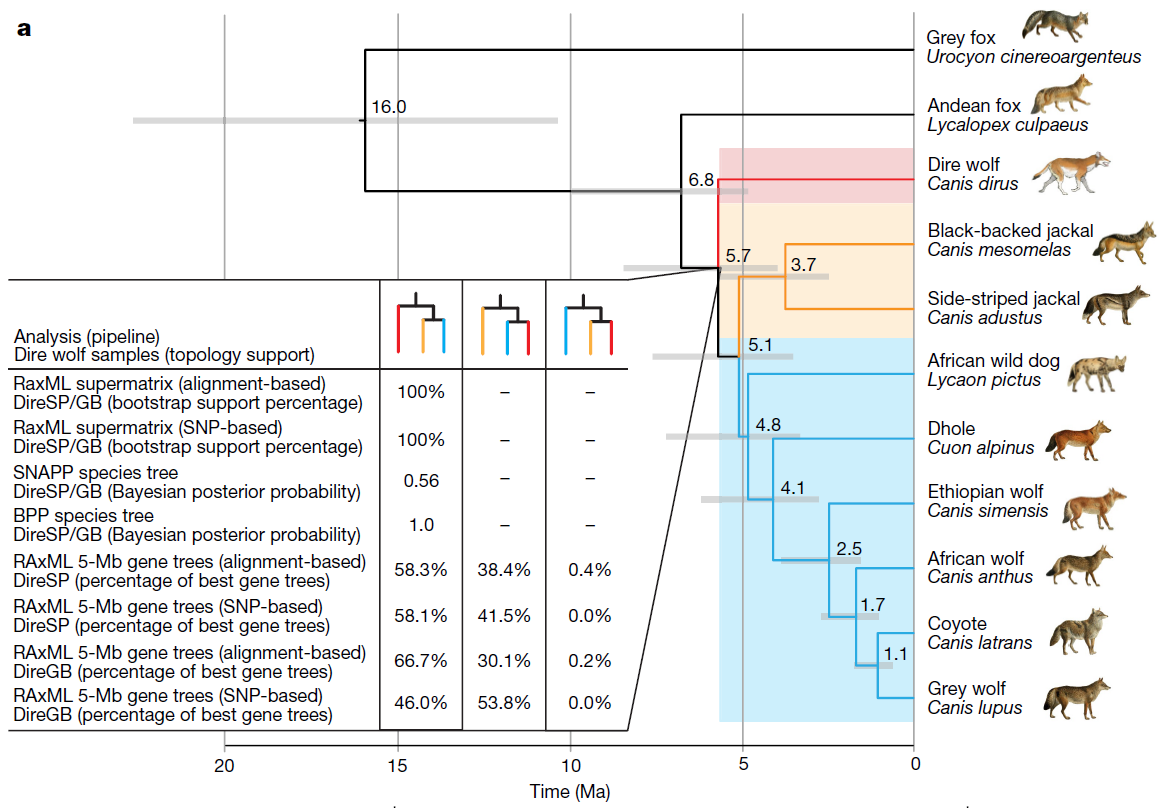

Even though there is a substantial record of dire wolf fossils (more than 4,000 have been discovered at the La Brea Tar Pits in California alone), little is known about where these large wolves fit on the canine family evolutionary tree.

Katherine Skerry, a recent graduate of the School of Human Evolution and Social Change, worked alongside experts as a student in this massive study to map the lineage of dire wolves and analyze their relationship to living wolflike members of the dog family.

The findings indicate that while dire wolves looked very similar to living gray wolves and coyotes, they weren’t very closely related. Their genes are so different that researchers suggest the dire wolf lineage breaks away from other North American dog species millions of years ago.

The findings also reinforce some common hypotheses, including that dire wolves likely did not mate with other species of wolflike dogs. This is important because it could mean dire wolves lacked the genetic diversity needed for the species to survive longer.

Anne Stone, an ASU Regents Professor and Institute of Human Origins research affiliate, specializes in ancient DNA and served as Skerry’s adviser for her research on dire wolves.

“We were really surprised to find no evidence of admixture (mating between species),” Stone said. “And what that points to, given how common admixture is in canids, is that those two lineages — dire wolves and gray wolves — must have been separated from each other for a long time.”

Skerry, Stone and Andrew Ozga, an ASU postdoctoral scholar, attempted to extract DNA from 19 dire wolf fossil samples. Unfortunately, DNA is fragile and naturally breaks down over thousands of years, so Skerry, Stone and Ozga were unable to recover any.

That’s partially why this research had to be a worldwide effort; of the more than 46 samples analyzed in the study, expert geneticists were able to gather full DNA information from only five.

Beyond ancient DNA, other scientists on this study mapped genomes from living canines like jackals and gray wolves, and compared physical attributes like jaw and teeth size. This information, combined with the ancient DNA analysis, helps create a better picture of where dire wolves most likely fit into the canine family.

An educational path through biology, anthropology and physical therapy

When Skerry, a “Game of Thrones” fan, considered a topic for her thesis as part of her curriculum with Barrett, The Honors College at ASU, she thought something combining dire wolves and ancient DNA would be a perfect fit. Stone knew of other researchers who were also studying dire wolf DNA at the same time and provided guidance for Skerry through the research process.

Stone also introduced Skerry to Greger Larson, a recognized leader in canine genetics at another prestigious university and a co-author of the study. Skerry spent a semester abroad, working with Larson in the lab as much as she possibly could while continuing her ASU coursework online.

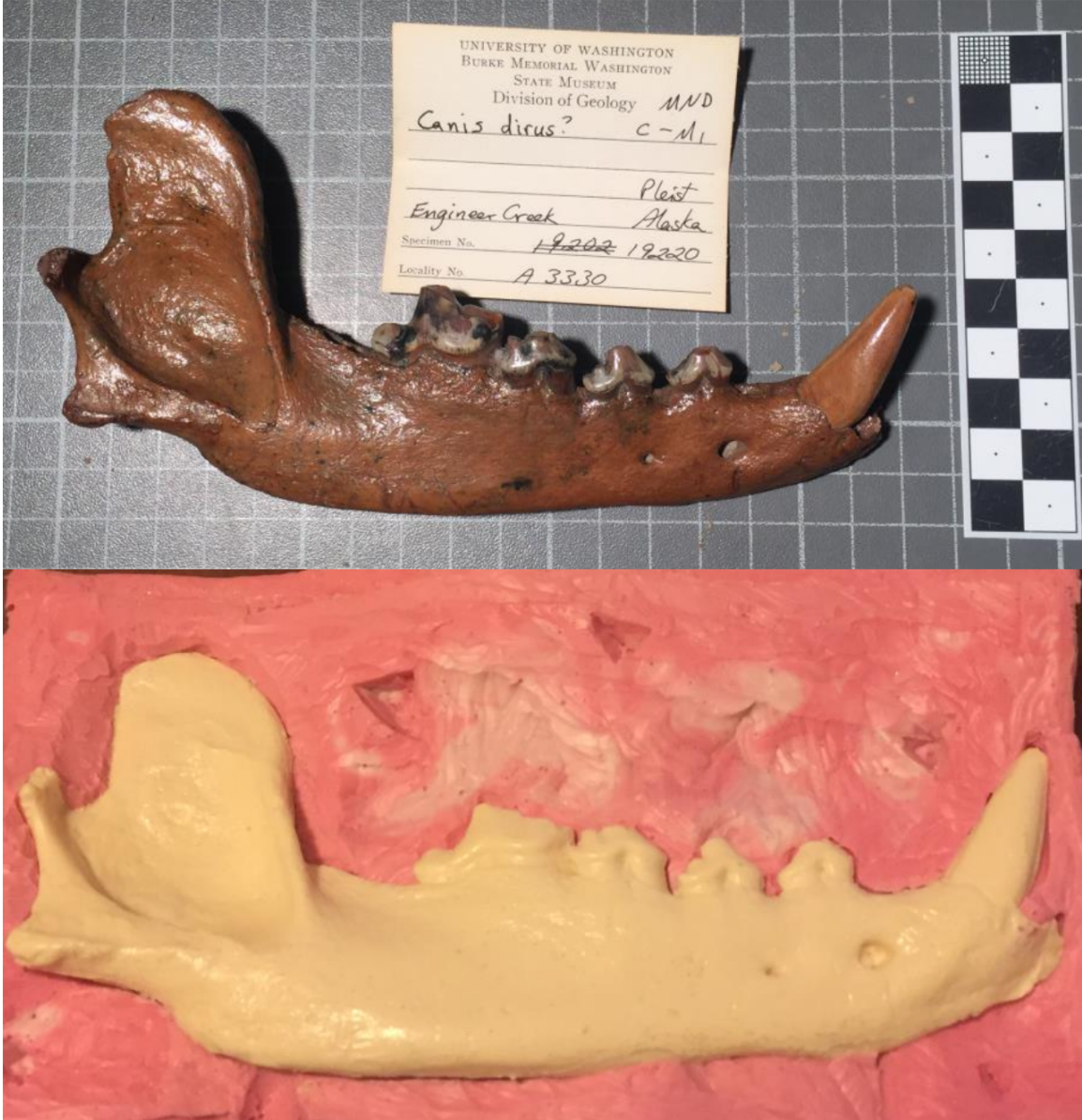

A dire wolf jaw fossil sent to Skerry for DNA analysis. Skerry prepared the mold of the mandible, below. Photo courtesy of Katherine Skerry

Skerry graduated in 2018 with Bachelor of Science degrees in biology and anthropology but was fascinated by evolution and genetics as far back as high school.

“I knew I wanted to do biology really early on,” Skerry said. “I loved my freshman biology class, and I was always interested in evolution — especially human evolution and human history. I also enjoyed learning genetics because I love figuring out how stuff works.”

The determined high school senior toured Stone’s lab at ASU and knew that was where she wanted to be.

“Basically, the minute I started at ASU, I was working in Anne’s lab,” Skerry said.

She is now working toward a graduate degree in physical therapy training from another university. Although seemingly a very different field of study, she wanted to try clinical work, and feels her education in anthropology and biology has prepared her well.

“The appreciation for the scientific process has been super helpful, as we do a lot of evidence-based practice in physical therapy,” she said. “Also, learning how to read scientific papers and how to think critically about evidence — these are all things I learned at ASU and in the lab.”

The paper “Dire wolves were the last of an ancient New World canid lineage” published this week in Nature.

More Science and technology

Statewide initiative to speed transfer of ASU lab research to marketplace

A new initiative will help speed the time it takes for groundbreaking biomedical research at Arizona’s three public universities…

ASU research seeks solutions to challenges faced by middle-aged adults

Adults in midlife comprise a large percentage of the country’s population — 24 percent of Arizonans are between 45 and 65 years…

ASU research helps prevent substance abuse, mental health problems and more

Smoking rates among teenagers today are much lower than they were a generation ago, decreasing from 36% in the late 1990s to…