Editor's note: This is the third of three parts of the story of ASU's geologists. Read the first and second installments.

Michael Crow became the 16th president of ASU in 2002. After he arrived, he met with the geology faculty. Ed Stump was at the meeting.

“He basically said, ‘Hey, you guys, you're the best department in the university, at least from the standpoint of dollars,’ which we were. I mean, at one point we had more money than chemistry or biology, and we had a third or half or less than half of the faculty per capita. We were way out ahead of the rest of the university,” Stump said. “And he said, ‘So give me a plan. What do you want to do?’ You know, it was carte blanche.”

After weeks of fumbling around and coming up with Venn diagrams with “no vision at all,” as Stump recalled, Crow, planetary geologist Philip Christensen (who had massive NASA funding) and some faculty who are no longer at ASU came up with the idea to merge with the astronomers from physics and make the geology department a superdepartment whose main emphasis was interdisciplinary geoscience and astrophysics research: the School of Earth and Space Exploration.

It started operations in 2006.

“Crow wanted something bigger and splashier and more interdisciplinary,” Professor Emeritus Jim Tyburczy said. “Not everybody was totally gung ho, but by far the biggest majority said, ‘Well, this is our path to the future. Let’s take it.’”

Ramon Arrowsmith came to ASU in 1995, bridging the Troy Péwé era with the creation of the School of Earth and Space Exploration.

“I got a few other offers, but this was really the best, the most interesting, I felt like the most challenging,” he said. “I'm also from Albuquerque. So I liked being in the Southwest.”

Arrowsmith studies earthquake geology, paleoseismology and the geomorphology of fault zones, publishing about their history of activity and hazards. He’s a field geologist. Prepandemic, he had racked up about 120,000 frequent-flyer miles. East Africa, the Himalayas, western China and southeast Asia are all places he has worked. He has floated the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon six times (including once with Péwé and again on the trip where Péwé called in on a ham radio).

Ramon Arrowsmith

“One of the exciting things that geology does is it gives you this ability to sort of see in four dimensions, you know, what's going on and what has happened and maybe think about what will happen,” Arrowsmith said.

Arrowsmith is now associate director of operations of the school. He has been called one of its key developers.

“I think what really propelled everything was the high stature, big missions, big money associated with planetary science,” he said. “But to do it well you have to have some good geologists around who are studying the Earth because Earth analogs training of those planetary scientists, so there’s that partnership.”

It all runs together

Kip Hodges came to ASU in 2006 to be the founding director of the School of Earth and Space Exploration, a position he held until 2013.

Ask him where his research lies and he’ll give you a 15-minute, four-paragraph answer. Continental tectonics. Structural geology. Geochemistry. Geochronology and thermochronology. Planetary science.

“So it's not an easy answer to your question,” he said. “I'm sorry. I can't just say, ‘This is the field that I pursued.’”

For geologists today, that’s a common answer. It all tends to run together.

“That's one of the goals of the school and one of the reasons I was recruited to be the founding director,” Hodges said.

Kip Hodges

Hodges came from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. One of his tasks there was to try to get engineers and scientists to work together better than they historically had.

“I had done a lot of work on that, and had a lot of success on that,” he said.

The idea was this new school was going to have geological sciences, planetary sciences, astronomy, astrophysics, cosmology and forays into systems engineering. Hodges liked the idea.

“President Crow was kind enough to make it a presidential initiative at ASU,” he said. “And so he put lots and lots of resources into it to make it the great school that it is right now. So that's what convinced me to come and do it.

“It was not a particularly hard sell when I heard the description of what the school was going to be. … I won't lie to say that there were no bumps in the road, but on the other hand for the most part, the faculty were very engaged and very enthusiastic and bought into the vision for the school. And so any success I had was directly associated with how willing the faculty at ASU were to buy into that.”

The school’s astronomers and astrophysicists have benefited from rubbing elbows with the geoscientists. The perfect example is the hottest field in astronomy and astrophysics now: exoplanets. As of December 2020, 4,307 have been confirmed, according to NASA. There are 5,683 candidates.

In the early years of exoplanets, it was really just about looking at brightness variations as something passed in front of a star to identify the existence of an exoplanet. Now scientists are getting to the point where they have to think about exoplanets as planets. Geoscientists know an awful lot about the evolution of one planet in particular.

“It's a beautiful connectivity between astronomy, astrophysics and geological sciences, if we can take advantage of it,” Hodges said. “We're trying hard to take advantage of that. So I think it's a great evolution. The thing we have to understand is that those kinds of broad integrative ways of looking at problems are spectacularly important. … The problem is that to do transdisciplinary science very well, you’ve got to make sure that you have rock-solid disciplinary science. And that's the difficulty in building a university program like the program we have: If we become too planetary, or if we become too astrophysical, or if we become too geological, we actually tilt the balance. … How do we stay deep, but also broad?”

Working in the spaces between

Kelin Whipple is a geomorphologist interested in the interactions among climate, topography and tectonics. He worked with Hodges at MIT. When Hodges was hired as the founding director of the School of Earth and Space Exploration, he urged Whipple to join him.

“It was just the excitement to come be a part of something new,” Whipple said. “Just to try to break new boundaries and do things that hadn't really been done before.”

Faculty at the school work on developing interconnections in the spaces between different classical fields.

“We don't really like to think of a strength in this or that,” Whipple said. “We like to think of we've got the strength to tackle this problem or that problem, wherever it might lie, in terms of disciplinary boundaries.”

Kelin Whipple is a geomorphologist interested in the interactions among climate, topography and tectonics — and in the interactions between the space and geology segments of the school. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU

Rather than thinking of the strength of one group over another, Whipple looks at the school like an M.C. Escher staircase.

“I'm probably never going to directly collaborate with, say, Evan Scannapieco, who works on the evolution of galaxies and so on, but you can follow a chain of people I work with and who they work with and you can follow that channel all the way around and you're going to get to someone with a collaboration with Evan Scannapieco. … It's pretty cool that there is a link that you can follow between any faculty member and another and have interactions.”

Fifty years ago that wasn’t the case.

“That’s the idea,” Whipple said. “To change things.”

Like the lion and the lamb, the geomorphologist is unlikely to lie down with the astrophysicist. Unimportant, Whipple said.

“We do still speak a pretty common language, right? We work with the same kind of differential equations. The same physics applies, just in different environments and different people need to get into physics to a different level to do their work. But there's still a common language and a common approach to what you do to do science.”

The new generation: The warrior poet

Arjun Heimsath is a classic warrior poet. Raised on a Texas Hill Country ranch and in the Himalayan foothills, he climbs cliffs and mountains, races triathlons, writes poetry and speaks Hindi, Kiswahili and Nepali. When he was a child, his parents — father a Texan professor, mother an Indian professor — drove him and his brother from Germany to India in a VW bus, spent two years traveling around, then drove back.

“I think that childhood combined with them, this passion to connect what humans are doing to the landscape, with how the landscape is operating, really brought home the importance of quantifying how our Earth surface works,” he said. “That just still resonates with me and still plays a role, I think.”

A geomorphologist by accident, he has worked in Australia, Tibet, South Africa, the Himalayas, Kenya, Alaska and Chile. He earned a degree in mechanical engineering from Yale and joined the Peace Corps in Kenya working in water development.

Professor Arjun Heimsath does infiltration experiments in the Atacama Desert a couple years ago, with surface temperature above 130 degrees. Photo courtesy of Arjun Heimsath

“That connection between what humans did to the Earth surface and water quality and water supply switched me from being an engineer to being an environmental scientist/geologist,” he said.

Heimsath didn’t study geology as an undergrad. He didn’t go on field trips or culminate his studies in field camp.

“I didn't actually recognize that this whole notion of field work was so integral to geosciences until I was a PhD student, and then very early on in my PhD training, I was working on a problem,” he said. “My adviser … had me work on a computer model of what we were doing for this problem. And I hated it. I just hated it. I basically decided then that I was going to focus on field work rather than the modeling part. I mean, obviously you have to model in order to interpret your fields yourselves, and you have to model to actually tell a good story. But I think one of the aspects of my work that sets it aside, in some ways — my emphasis has always been about collecting samples and then making the measurements that are all field-based. And sure, I love being in cool places.”

Heimsath and three of his colleagues are working on a summary talk about the future of geomorphology for the upcoming American Geophysical Union conference. (One of the world’s biggest scientific conferences, it’s Lollapalooza for geoscientists. The School of Earth and Space Exploration has a booth there every year.)

The take-home message that Heimsath really wants to convey is to get off the computer and get out in the field and get back out on the landscape, because what is happening is so many earth scientists don't ever leave the computer screen anymore.

“It's all done right here, instead of actually being out there digging holes or banging on rocks or collecting stream samples or measuring how much water is going down a river,” he said.

Geomorphology is not like working on NASA missions. The public has no idea about any of it, and your chances of appearing on CNN are slim to none. Heimsath jokes that surface-process scientists just dig holes on small budgets and drive down dirt roads.

“We don't get a lot of attention, but that's fine,” he said. “We love what we do. But in the surface-processes communities, ASU is known to be a very strong player.”

The new generation: The accidental volcanologist

Many people, including several you’ve heard from in this story, stumble into geology by accident, get hooked and pursue it as their life’s passion. Amanda Clarke is one of them.

She started as an intern aerospace engineer at Boeing, working on the 777. Boeing’s plant is close to Mount St. Helens, which caught her attention. The company offered Friday afternoon lectures, and one such was about what happens to aircraft when they fly through volcanic plumes. A chief pilot trainer discussed a KLM flight where all four engines failed and the plane nearly crashed, along with similar incidents.

“And so that got me really interested,” Clarke said.

Associate Professor Amanda Clarke is at the LUSI mud volcano site in East Java, Indonesia. It looks like a construction site because they are trying to contain the mud using human-made levees. Photo courtesy of Amanda Clarke

She wrote a Fulbright fellowship application to study sociocultural interactions with volcanic environments in the Philippines. Eventually she wound up studying for her PhD with a Penn State volcanologist. She has studied volcanoes in Italy, the Caribbean and Indonesia, as well as dead volcanoes in Arizona.

“What I do in volcanoes and volcanology is a good mix of field science, but it kind of uses my background in fluid mechanics,” she said.

Volcanologists are rare at U.S. universities (in a European institution there are often six or seven together). Clarke came to ASU because she liked the environment, and the fact that the university has a legacy of volcanology. The science, like every other branch of geology, has evolved into an interdisciplinary tree.

Associate Professor Amanda Clarke (left) is on La Fossa cone in Italy, collecting volcanic ash samples with graduate student Jisoo Kim. The eruptions are from about 1500–1890. Photo courtesy of Amanda Clarke

“If you're a volcano scientist, you have to at least understand the language of lots of different things,” Clarke said. “So if you're looking at an active eruption, then you have to kind of understand the language of a seismologist, a geodesist, a petrologist and a gas geochemist, and what the deposits look like and the physical processes. … That's one of the things I like about volcanology: If you work on active eruptions, you get to rub elbows with different kinds of engineers and geophysicist and chemists. I find it really fun.”

The new generation

Melanie Barboni is one of the most recent School of Earth and Space Exploration hires in geosciences. She studies volcanoes, the formation of the moon, the early evolution of the solar system and rocky planets.

“I am the kind of person who gets bored if I just stay in the same field, because one field is not representative of the whole picture you need,” the Swiss native said. “It's a complex system. … And that is the reason I wake up every morning still feeling excited about my job because it is not always the same thing. And at the end of the day, I feel like I have a better understanding of the big-picture processes if I don't only look at one tiny detail of each one of them, you know what I mean?”

Plus, she finds lunar samples and meteorites irresistible. Barboni has always found rocks irresistible.

“When I was a baby, I was already grabbing rocks around my blanket and putting them in my nose and in my mouth, which was trusting (of) my parents. And then when I was able to work, I just collected product and my room was full of rocks. … I spent my whole childhood and teenage years collecting rocks and reading books about gemstonesm,” Barboni said. “And then I got interested in the processes behind them. And I asked my parents, ‘What does it take to be a geologist?’ And I was maybe 7 at the time.”

She came to ASU in 2018. It was the last of three interviews. The first two felt like interviews. The school did not.

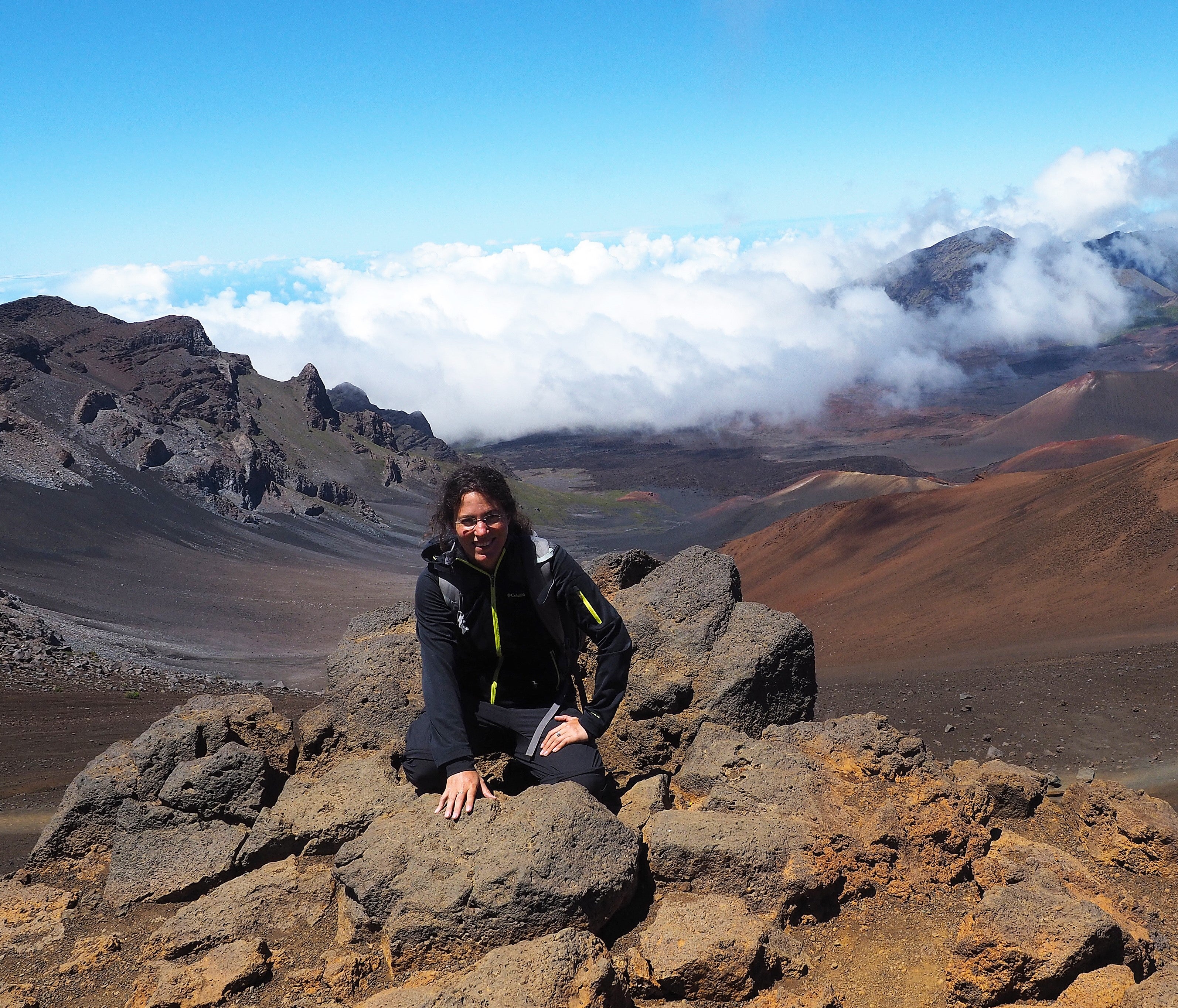

Assistant Professor Melanie Barboni is on the Haleakala volcano on the Hawaiian island of Maui on June 20, 2016. Photo courtesy of Melanie Barboni

“I had fun with my colleagues,” she said. “It was like an exchange of science. It was fun. They were awesome. And I felt like I'm a people person and I really need a family. Because I left mine in Switzerland. I felt that the department could be. And also, it turns out that the department was the best one by far.”

Barboni trained as a geochemist. “I can offer a lot of tools to people,” she said. On her resume is a list of exotic analytical tools she works with: laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, isotope dilution thermal ionization mass spectrometry and others.

“I don't think people at (the School of Earth and Space Exploration) see themselves as a little clan,” she said. "This is what makes this department very different. We are one block. … I have common interests with Christy Till. And I have a lot of common interests with Ed Garnero because we would like maybe to investigate how geochemistry and geophysics can be used together. We also have other interests outside (the school). Actually, he does woodworking — I do too. He's a musician — I'm also a musician. So he's a great friend.

"I have a connection with everyone there,” she said. “Every time I talk to a colleague, there is always that possibility that there could be a collaboration.”

And collaboration will continue to be the key to unlocking the mysteries of mountains and volcanoes, deserts and canyons, the seen and the unseen.

"Oh, this smile that I have on my face is a geological smile — a smile of who knows, looks at something, sees and understands. This very ravine is an open book to me, a page of Earth’s history on which I read a thousand fantastic things.”

— Monteiro Lobato, "O Poço do Visconde," 1937

Top photo by Pixabay

More Science and technology

ASU professor breeds new tomato variety, the 'Desert Dew'

In an era defined by climate volatility and resource scarcity, researchers are developing crops that can survive — and thrive — under pressure.One such innovation is the newly released tomato variety…

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…