Many historians have stated that this country was founded on the exploitation of Indigenous peoples and the Earth.

Their land has been colonized for centuries. Resources such as water, minerals and wildlife were once honored and abundant, but now are polluted and scarce.

This history is why Native Americans have been consistent allies to environmental movements.

Arizona State University’s Project Humanities hosted a Nov. 17 livestream event titled “Environmental Justice: Indigenous Communities” to explore the intersection of justice for the Earth, justice for Indigenous peoples and how to mend the wounds of the past.

“If nothing else, the summer 2020 crisis in racial justice has forced conversation about systemic racism to name ‘white supremacy’ as the proverbial unnamed monster in the room,” said Neal A. Lester, professor of English and director of Project Humanities. “That many are looking at racial (in)justice in its myriad manifestations and permutations is exactly why this conversation about Indigenous communities and lands is imperative and beneficial. That we have such a panel of experts doing this work is truly an honor. Our desire is that coming together for this conversation will move us all to some action — great or small — to make us better and to make us think differently about our relationship with each other and with the stolen land upon which this very USA created itself.”

The event panel featured Alycia de Mesa, a senior sustainability scholar for ASU’s Global Institute of Sustainability and Innovation; Melissa K. Nelson, professor of Indigenous sustainability in ASU’s School of Sustainability; Nicole Horseherder, executive director of Tó Nizhóní Ání, a grassroots organization focused on preserving and protecting the environment; Vanessa Nosie, employed with the San Carlos Apache Tribe Historic Preservation and Archeology Department as the NAGPRA project director and archeology aide; and her daughter, Naelyn Pike, an internationally renowned Indigenous rights and environmental leader and activist. Manuel Pino, a professor of sociology and coordinator of American Indian studies at Scottsdale Community College, served as the evening’s facilitator.

Together, the panel examined the roots of environmental racism, colonialism, corporate mining and its impacts to Native lands, water diversion to fill the need of larger cities, climate change, demonstrating empathy for Native American tribes and how to become an ally to Indigenous peoples.

Panelists at Project Humanities' Nov. 17 discussion on environmentalism and Indigenous communities include (top row, from left) sustainability instructor and PhD student Alycia de Mesa; San Carlos Apache preservationist Vanessa Nosie and her daughter, activist Naelyn Pike; Melissa Nelson, an ASU professor of Indigenous sustainability; (bottom row, from left) panel facilitator and Scottsdale Community College Professor Manuel Pino; and Navajo environmentalist Nicole Horseherder.

The group spent the first half of the program defining and tracing the roots of environmental racism. Pino, who hails from the Acoma Pueblo in New Mexico, said he grew up next to a uranium mine that contaminated the environment and claimed the lives of a handful of his relatives. Pino added that those same mines were abandoned decades ago and were never reclaimed or cleaned up.

“All of these companies have abandoned and left us with our contaminated aboriginal homelands,” Pino said. “It not only had impacts to the environment, but to human health.”

Nelson said the roots of environmental racism trace back more than 500 years to explorer Christopher Columbus. She cited American Indian thinker Jack D. Forbes’ book "Columbus and the Other Cannibals" as a vital text.

“He (Forbes) talked about how when Columbus first came here, he brought this spirit of conquest and this spirit of colonialism. And, of course, it was fueled by the Vatican and the pope’s Doctrine of Discovery,” said Nelson, an Indigenous writer, editor and scholar-activist. “That basically said that these Indigenous lands and the millions of people who are here are pretty much invisible because they’re not Christian and weren’t tending to the land properly … so it goes way back and it has many faces.”

Horseherder, a Diné from Black Mesa in northeastern Arizona, said years of coal mining decimated their land and polluted their water.

“In all of the years that I had been growing up there, there were no more springs. And all of Black Mesa, we don’t have running rivers and springs, and we had springs all over the plateau,” Horseherder said. “The springs near my home was also gone. And that’s where my search began.”

Horseherder added that the Navajo Generating Station coal-fired power plant near the Arizona-Utah border shut down a year ago and was a major victory, but the work continues.

“One of the things we have to make sure of now is reclamation will occur under the federal government,” Horseherder said. “We as Indigenous people have to stay vigilant and (make sure it) happens to the standard that we need it to happen so that people can go back and live on those lands the way they used to.”

Nosie said environmental racism is much more than damage to Native land; it equates to cultural destruction and genocide.

“Our environment is a key source to our identity and who we are as Indigenous people,” said Nosie, who is a community organizer for her tribe. “Our cultural resources come from the Earth in order to conduct a lot of our resources. So when you talk about environmental racism, you’re talking about cultural destruction and genocide on our people.”

De Mesa, a fourth-generation Arizonan whose heritage is a mix of Mexican, Western Apache, Indigenous Mexican of Durango, Japanese and British/German, said it’s every non-Native’s duty to inform themselves about the history of these lands and become an ally.

“We need to understand what is our environment, especially if you’re someone living in a big city,” de Mesa said. “Where does our water come from? Where does our energy come from? What are the backs that are being broken for you to enjoy Wi-Fi, electricity or anything else? We have to understand this historically, and we have to understand what’s happening in the present … investigate, ask questions, read. Obviously, empathy is a huge part of this.”

Pike said taking action by putting pressure on political leaders is not only effective, but every citizen’s right.

“Make your voice be heard because we are the people, we elect them to represent us so your voice needs to be heard,” said Pike, who co-leads (with her grandfather Wendsler Nosie Sr. and mother Vanessa Nosie) the nonprofit Apache Stronghold, which is fighting to stop a mining project that they say would desecrate Oak Flat, an Apache sacred site near the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. “Ask the question, ‘Who am I? Where do I come from?’ You’ll find a connection not just to yourself and your people, but it’ll also help you connect to what we’re trying to do.”

Pino said getting corporations and politicians to stop desecrating Native land has been a lifelong battle for him and others. It's something Pino said he may not see come to fruition during his lifetime, but he's not stopping no matter what.

“I started as a young man. Now I’m an old man,” Pino said. “And we’re still fighting.”

Project Humanities' suggested action items for the public

- For more information on the fight for Oak Flat, visit apache-stronghold.com.

- For more information on how to protect Black Mesa aquifers, visit facebook.com/tonizhoniani.

- For more information on ASU’s Native American Heritage Month, visit eoss.asu.edu/student-and-cultural-engagement/heritage/native-american-heritage-month-calendar.

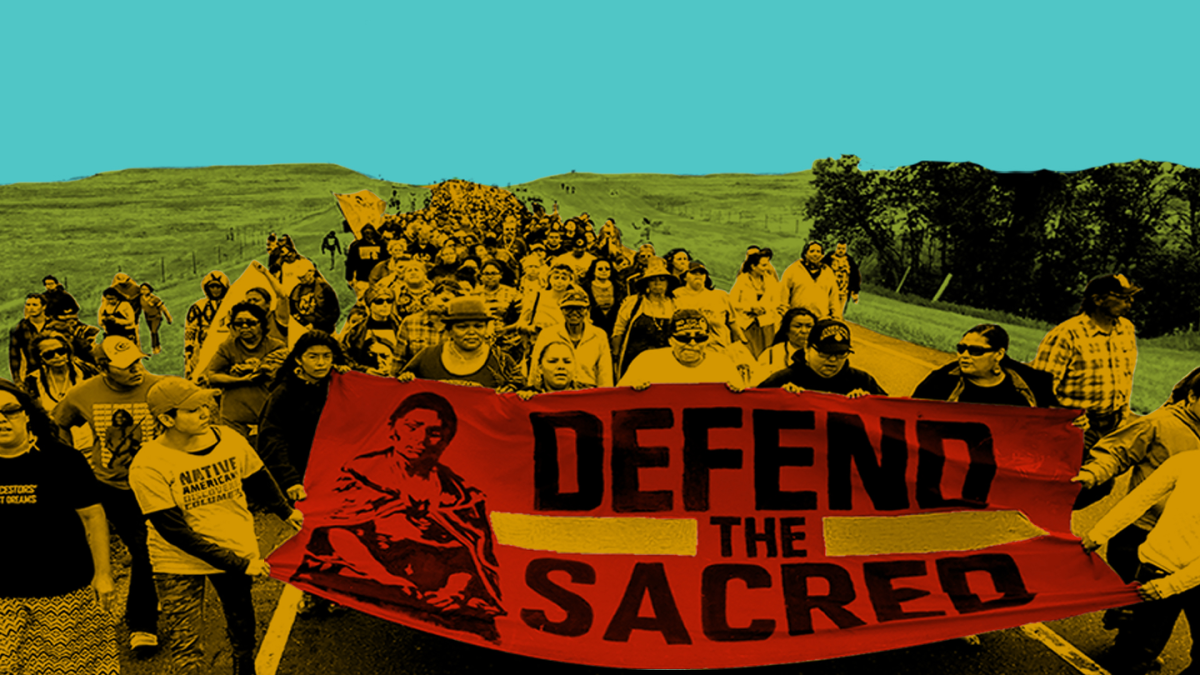

Top image courtesy of Project Humanities

More Science and technology

Large-scale study reveals true impact of ASU VR lab on science education

Students at Arizona State University love the Dreamscape Learn virtual reality biology experiences, and the intense engagement it creates is leading to higher grades and more persistence for biology…

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity of low-mass stars, has now passed its pre-shipment review by NASA.…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the transformation ASU is driving through its microelectronics research…