ASU strives to promote and advance Native American higher education

It was seeing herself reflected that made the college decision for Maria Walker.

The high school senior had been all set to go to Columbia University on a full scholarship, but then Tribal Nations Tour visited her school in the White Mountain Apache community. The outreach program brings Arizona State University students to schools throughout the state with large populations of American Indian students.

That spring 2017 visit made all the difference for Walker.

“It was heartwarming to see other Native Americans from ASU, who were successful and took the time to share their stories with us,” said Walker, now a senior in ASU's College of Health Solutions. “It made me realize that if I went to ASU, I’d be studying with fellow Native Americans and be taught by Native staff who could help me along the way.

"I decided that I’d rather have a community at ASU rather than travel across the country and not know anyone or have the support I have now.”

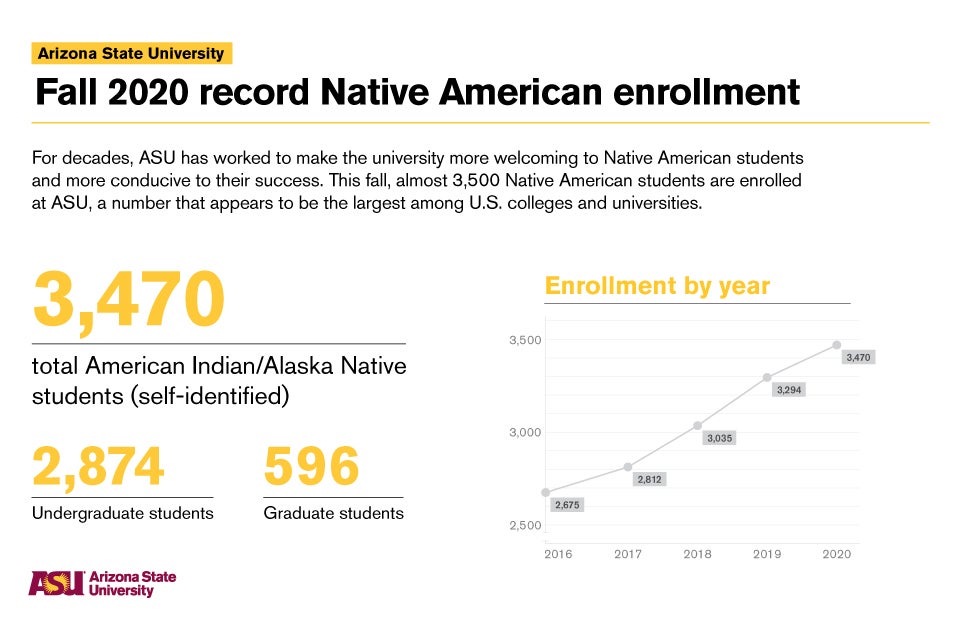

Walker is part of a growing number of Native American students at ASU, which reached almost 3,500This number reflects students who self-identify as Native American. ASU's enrollment according to IPEDS — the data program for the National Center for Education Statistics that is commonly used to compare institutions — is lower, because if a student identifies as both Hispanic and Native American, the Hispanic category takes precedence and the student is counted only as Hispanic. — 2,874 undergraduate and 596 graduate students — this fall. That number appears to be the largest among U.S. colleges and universities, according to ASU Now's research. ASU also is one of the nation's leaders in degrees granted to American Indian students on an annual basis; for the 2019-20 academic year, 663 Native American undergraduate and graduate students earned 679 degrees here.

Maria Walker, shown here on Palm Walk on the Tempe campus, chose ASU in order to be part of a community of Native American students. Photo by Ashlyn Young

American Indian students make up less than 1% of all college students in the U.S., according to the National Center for Education Statistics, and only about 13% of all Native Americans have a college degree. Those numbers are starting to change, and ASU — whose Tempe campus sits on the ancestral homelands of many Indigenous peoples, including the Akimel O’odham (Pima) and Xalychidom Piipaash (Maricopa) — is striving to do its part.

"There is so much potential here, and indeed, potential that is already being realized in very big ways," ASU President Michael M. Crow said. "There is unbelievable energy to be found by asking, 'Where is there opportunity to grow in understanding?' ASU is making it a priority to serve Native American students, and in turn, these students are enriching the ASU community."

What follows is how ASU got here, and how it is working collaboratively with tribal nations to help them become stronger and more vibrant by building capacity. This work is accomplished through community engagement, research and offering place and space for American Indian and Alaska Native students, faculty and programs to create futures of their own making.

The beginning of a change

Sixty years ago, when ASU opened the Center for Indian Education, the university had 17 Indigenous students enrolled at the university. Peterson Zah, the last chairman and the first president of the Navajo Nation and a consultant to ASU's Office of Tribal Relations, first attended the university in 1959. He said getting to ASU was an adventure and an education in life.

Zah packed his luggage — a brown paper sack — placed his clothes and whatever possessions he owned in it, and hopped in the back of a pickup truck, commandeered by his uncle with his aunt riding shotgun.

“On the way down from the reservation, we stopped at a store in Payson to eat and gas up,” Zah said from his home in Window Rock, Arizona. “I could barely read or speak English, but I noticed a sign in the window that read, ‘Any good Indian is a dead Indian.’ I asked my uncle what that was about. He shrugged his shoulders and said, ‘People are just that way around here.’

“I asked him, ‘What am I going to school for?’” Zah said.

Soon he would find out — to help build capacity for his people and other tribes. When Zah graduated in 1963 with a degree in education, he had several jobs. He taught high school in Window Rock, worked as a construction estimator for the tribe, did a stint with the AmeriCorps VISTA volunteer program, and helped the Mashantucket Pequot Tribe build the one of the earliest major Indian casinos in Ledyard, Connecticut. In 1995, Zah was hired and tasked by then ASU President Lattie Coor to look for innovative ways to increase the number of American Indian students at ASU, which numbered 672 at the time.

Twenty-five years later, that number is far more substantial.

Regents Professor Donald Fixico. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

“I have always marveled at the number of American Indian students receiving their degrees every year in December, and especially at spring graduation in May,” said ASU Regents Professor Donald Fixico, one of the nation’s preeminent American Indian history scholars. “It is impressive to see all of the families, relatives and friends that fill the auditorium. At last, ASU has reached a milestone by graduating more Native students than any other university in the United States. This says a lot — that ASU is a university that welcomes and supports American Indian students.”

Rising above the challenges

The COVID-19 pandemic has hit tribal communities particularly hard in 2020. Long-standing health disparities have left American Indian people more vulnerable to the pandemic. Relatives and family members have died. Reservations have implemented weekend-long lockdowns and curfews. Inadequate infrastructure in water, housing, education, health care delivery and limited or no broadband accessibility has been exacerbated, and funding for scholarships have taken a big hit.

But that didn’t stop American Indian students from seeking their education. This group has historically been driven by a sense of community and purpose, according to Bryan McKinley Jones Brayboy, President’s Professor, director of the Center for Indian Education and ASU’s senior adviser to the president on American Indian affairs. Native students often get a degree to pay it forward, by going back to their community and helping to strengthen and sustain it.

Students like Mariah Black Bird.

The 27-year-old is a citizen of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe in South Dakota, and she is enrolled in ASU’s Indian Legal Program in the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law.

With financial burdens growing up, the death of her father when she was 14, and coming from an impoverished tribal community, Black Bird has had a lot of obstacles to overcome. But she knew education was her pathway to a brighter future.

“There were a lot of sacrifices that had to be made. I sold my car, worked summers and my mom let me borrow her car to come down to Phoenix,” said Black Bird, who is on an ASU scholarship, which she says covers about 75% of her costs. “Sometimes I don’t get to have a social life because I have to study, or I need to stick to a budget because things are tight. But I know it’s only temporary.

Mariah Black Bird. Photo by Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law

“I look at our history and know that even though we’re no longer battling it out at Wounded Knee or other famous sites, we’re still fighting. … I want to try to help my tribe any way I can, and our weapon of choice has to be education.”

That’s a statement that resonates with Megan Bang. As the senior vice president of the Spencer Foundation and as a learning sciences professor at Northwestern University, Bang believes that higher education degrees for Native peoples is of the utmost importance for tribes and also advances the possibility of a just United States.

“The success at ASU is remarkable on multiple fronts, and the multitiered work is critical to appropriately recruiting and serving Native students,” said Bang, an Ojibwe tribe member and renowned researcher who serves on the Board on Science Education at the National Academy of Sciences. “ASU has also made substantial investments in Indigenous faculty and staff, Indigenous research and dedicated centers, support for students to engage in and with each other around important communal and cultural practices, and long-term partnerships with Indigenous communities, amongst other remarkable efforts.”

Bang added: “The university has built the institutional capacity to serve Native students with a rigor and seriousness unparalleled. ASU’s leadership is a model for the rest of us to learn.”

From the reservation to the campus

In the not-so-distant past, an academic recruiting trip to a reservation in the state of Arizona was almost inconceivable. The trips were long and the reservations were hard to navigate, with populations spread out over wide spaces. The barriers were great.

That mindset changed about a decade ago, said Annabell Bowen, director of American Indian Initiatives for the Office of University Affairs. That’s when her team, with the help of Zah, created the Tribal Nations Tour outreach program. Each year, the tour holds presentations on wellness, college readiness, career preparation and the pursuit of academic degrees.

“ASU can’t be viewed as invisible, and we’re not waiting for students in tribal communities to come and visit us,” said Bowen, who schedules visits to all of Arizona’s tribes and has plans to visit other states such as California, New Mexico and South Dakota. “Through these visits, Indigenous youth are able to see themselves in our students and faculty.”

Then-ASU senior and Miss Indian Arizona Shaandiin Parrish speaks to a group of students at the Fort McDowell Yavapai Nation reservation on Nov. 5, 2016, as part of the Tribal Nations Tour. Parrish spoke with youth in the community to inspire them to further their education. Photo by Anya Magnuson/ASU Now

In addition to the Tribal Nations Tour, ASU has built a suite of programs to recruit, retain and build a sense of community for its Indigenous students.

Those pathways begin with RECHARGE, a one-day college and career readiness day put together in collaboration with ASU’s Educational Outreach and Student Services. In spring 2019, the program attracted approximately 700 American Indian students from around the state. The second offering is INSPIRE, a weeklong summer bridge program for high school students that, pre-COVID-19, drew more than 250 applications for 100 slots. Another community engagement program is SPIRIT, a two-week final ramp-up orientation before the start of the fall semester for incoming American Indian first-year students. The program moves students into the dorms early in order to get acclimated to their new environment and make new friends in anticipation of often-experienced culture shock during what, for many students, is their first time away from home.

“Many times when Indigenous students come to this university to visit our campus, they are accompanied by their families,” Brayboy said. “Nine times out of 10, the parents will say to us, ‘We are entrusting you to take care of our child.’ It’s a promise and responsibility we take seriously at the university.”

Additional resources are the American Indian Student Support Services, the Alliance of Indigenous People student-led coalition and the American Indian Graduate Student Association.

Window Rock High School sophomore Quentin Tsosie (left) works with mentor and Assistant Professor Henry Quintero during ASU's Inspire Program for Native high school students held at Coor Hall in Tempe on June 23, 2017. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Beyond creating a welcoming environment, ASU realizes that connection is a worldview in how Native Americans are brought up, and that leaving the reservation is, in a way, a loss. Staff have worked hard over the years to present experiences of connection, belonging and shared identity. The university does that in a variety of ways and initiatives.

In 2017, ASU began publishing Turning Points, a first-of-its-kind magazine that comes out twice a year. It is geared specifically toward Native American students and is written by an all-Indigenous staff of students.

A year later, the Dream Warriors, a collective of Native American artists, came to ASU’s Tempe campus to kick off the “Heal It Tour,” which included two days of poetry, music, sharing, self-empowerment and healing.

For more than three decades, the university has hosted the ASU Pow Wow. The annual event draws thousands of spectators representing more than 100 tribes from around the U.S. and Canada for a three-day gathering. In April 2019, dancers and singers wore traditional regalia and continued the social and spiritual practices of their ancestors in Sun Devil Stadium, the first time the event had been held at the stadium since its inaugural year in 1986.

At the West campus, the Veterans Day Weekend Traditional Pow Wow has been a campus fixture since 2000. Unlike the spring event on the Tempe campus, which is a dancing competition, the West one is a traditional social gathering whose focus is honoring the military service of Native Americans. Because of COVID-19, its 20th anniversary will be celebrated in 2021.

The university also has plans underway to redesign the campus to reflect Indigenous culture. Last year, the ASU Library announced its expansion of the Labriola National American Indian Data Center, which features thousands of books, journals, Native Nations newspapers and primary source materials, such as photographs, oral histories and manuscript collections. The Labriola Center now has two locations; Fletcher Library on the West campus and Hayden Library on the Tempe campus.

Future ideas include adding traditional Gila River pottery artwork to Sun Devil Stadium and building a storytelling pavilion and gathering place on campus. A “welcome wall” that includes the languages of the nearly two dozen tribes in Arizona was incorporated into the renovated Hayden Library.

Through these efforts, ASU is raising awareness of its Indigenous connection to all students, not just Native Americans.

Seeing themselves in faculty

When Native students arrive on campus and are taught by Native faculty, they don't just see their physical selves reflected, they also find a reflection of their experiences and values of community, said Natalie Diaz, a poet, associate professor in ASU’s Department of English and winner of a 2018 MacArthur "genius" grant.

“ASU is building a community in which our Native students won’t have to become someone else to arrive here and succeed, and where they instead can be themselves and who they are will be impactful to our entire community at ASU,” said Diaz, who was born and raised in the Fort Mojave Indian Village in Needles, California, and is an enrolled member of the Gila River Indian Tribe.

“One of the things I love about being at ASU is that I have the freedom to be 100% Native while I’m here, as well as all the other things I believe I am. It isn't necessarily a new home; rather it is an extension of my home, which I carry with me everywhere I go.”

Associate Professor Natalie Diaz. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Diaz is one of many world-class Native professors at ASU. Others include Brayboy (Lumbee), director of the Center for Indian Education; Gary F. Moore (Powhatan Pamunkey) assistant professor in the School of Molecular Sciences and a researcher in the Biodesign Center for Applied Structural Discovery; K. Tsianina Lomawaima (Mvskoke/Creek Nation) in the School of Social Transformation; and Fixico (Shawnee, Sac and Fox, Muscogee Creek and Seminole) in the School of Historical, Philosophical and Religious Studies — all of whom have either been inducted into major academies or had significant awards bestowed upon them.

In the last year alone, ASU added several new Native American faculty hires. One of them is Matthew Ignacio, an associate professor in the School of Social Work.

“I feel like I hit the jackpot because this is where I’m supposed to be,” said Ignacio, a member of the Tohono O’odham Nation who specializes in the study of diversity, oppression, healing and wellness of Native Americans. “ASU is so vibrant on so many levels and across all four campuses. They work with tribal nations and understand the challenges of Native American students. I’m honored to be in this position and to give back to the students. I want to be a role model.”

So does Benjamin Timpson, an associate professor in ASU’s School of Art who runs a nationally ranked photography department.

“I love being at ASU because it’s an incredible place to be and they have a built-in outreach platform for Native American students,” said Timpson, who is a Yale-Smithsonian Poynter Fellow and descendant of the Pueblo Indian Tribes. “I’ve been at other schools where it’s an every-man-for-himself kind of place, and those are not healthy institutions. Not here. They really do a great job of building people up. Students come here and right away they’re all treated as equals no matter what level they were in the past. This is a very progressive place.”

The university’s latest superstar hire is Professor Rebecca L. Sandefur, a sociologist with the T. Denny Sanford School of Family Dynamics. Sandefur, who won a MacArthur “genius” grant the same year as Diaz, said she is impressed with her new academic home.

“The ASU Charter highlights the importance of serving ASU’s many communities and fostering inclusive success,” said Sandefur, an enrolled member of the Chickasaw Nation. “As Native American faculty, I am gratified to learn that ASU is the No. 1 educator of Native Americans in the country. I look forward to ASU’s continuing progress in supporting the success of Native American students.”

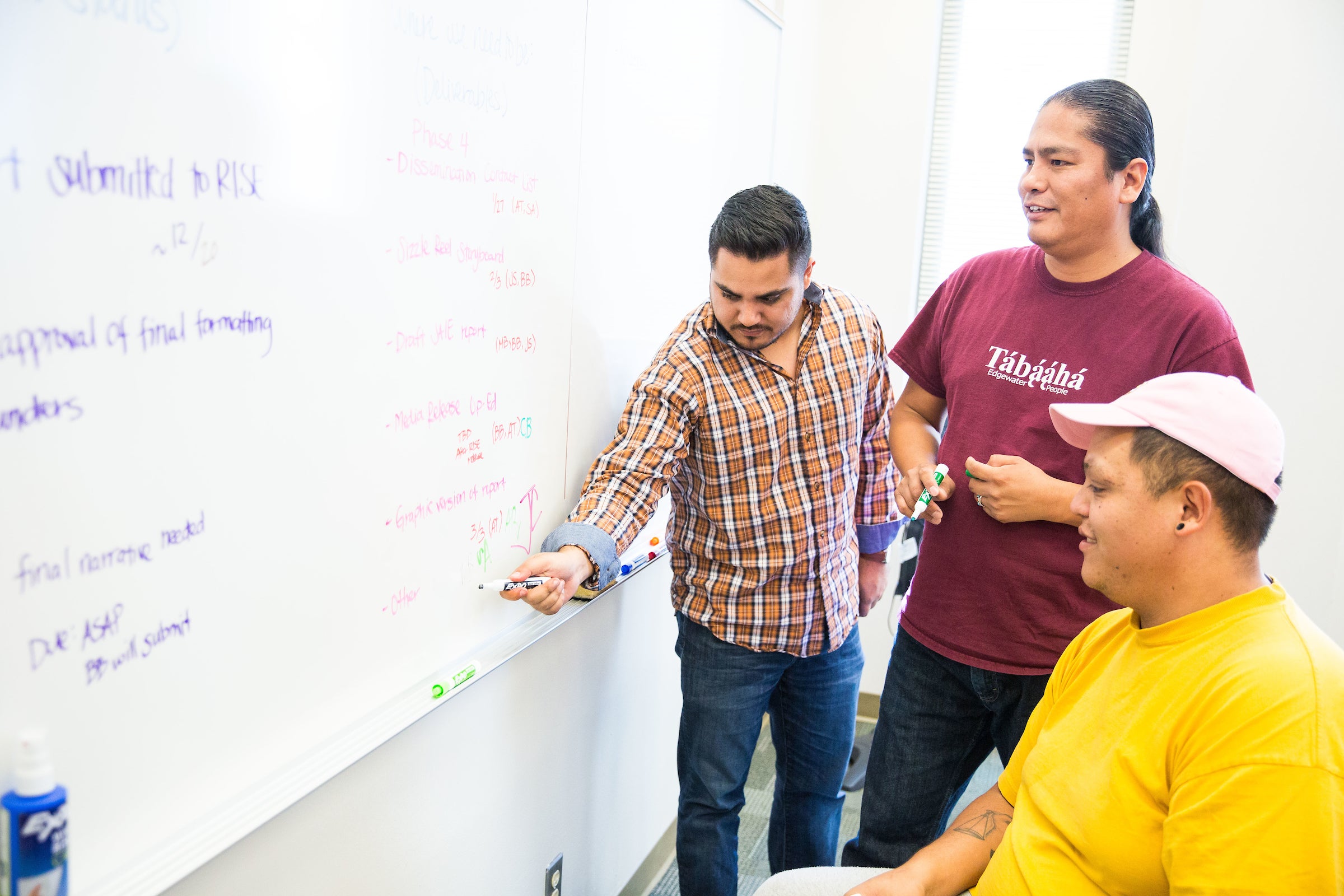

From left: Justice studies student Nicholas Bustamante, Assistant Research Professor Colin Ben and justice studies JD student Jeremiah Chin assign tasks during a weekly meeting at the Center for Indian Education on Feb. 1, 2017. The center is celebrating its diamond jubilee this year. Photo by Deanna Dent/ASU Now

Success is a two-way street

True success begins when you start giving back — that’s a lesson ASU has learned over the years when interacting with vibrant tribal nations, communities and students. ASU scholars also offer a spectrum of resources to tribes locally, regionally and beyond, and the university has a wide breadth of research and interaction taking place in Indian Country.

Last year, the American Indian Policy Institute at ASU offered an insightful and timely look at technology use on Indian lands. The paper, “Tribal Technology Assessment: The State of Internet Service on Tribal Lands” revealed that many Native Americans do not have equal access to the internet and are using smartphones to access it, although at much slower speeds and with less reliability.

Denise E. Bates, a historian and assistant professor of leadership and integrative studies in the College of Integrative Sciences and Arts at ASU, is nation-building through her work by helping tribes in the Southeast document their histories through community-driven initiatives. She does this through archiving material, recording oral history and writing books.

School of Social Work Assistant Professor Shanondora Billiot studies how climate change is affecting tribes in Louisiana due to rising sea levels. According to Billiot, the state's coastal areas have lost about 35 square miles a year for the last half century.

“Many who feel threatened by these changes have mental health challenges or meet criteria for depression, anxiety or PTSD,” said Billiot, who is a member of the United Houma Nation in southern Louisiana. “The second leg of my research is trying to discover what is the tipping point for people when they decide to move. It’s confusing and often heartbreaking.”

Realizing that many Native Americans live in remote areas, ASU has figured out a way to bring the campus to the reservation and other parts of the world. In 2012, ASU’s School of Social Transformation launched the Pueblo Indian Doctoral Program, which facilitates the training of practitioner-researcher-scholars within Pueblo communities in New Mexico. Five years later, the school also developed an online MA in Indigenous Education program that allowed students to stay within their own communities while strengthening their ability to work in the field of Indian education and within tribal nations’ education programs.

ASU is also civic-minded when it comes to helping tribal communities. The Native Vote Election Project through ASU’s Indian Legal Clinic aims to ensure that Native Americans exercise their right to vote in federal and state elections. The program trains volunteers to offer aid at polling sites around the state, helping Indigenous peoples navigate problems such as intimidation, acceptable forms of identification and legal procedures on Election Day.

The San Carlos Apache Tribe was able to open the third tribal college in the state in 2017 after 18 months of intense planning and preparation, much of it done with the assistance of ASU. Tribe Chairman Terry Rambler had a vision to create a college, and he asked Crow for help. The San Carlos Apache Tribe leveraged the expertise of Maria Hesse, then vice provost for academic partnerships at ASU, and Jacob Moore, the university’s associate vice president for tribal relations.

“I'm very thankful to ASU for what it's done for us and also for our people, because this is a game changer for our people,” Rambler said. “ ... Hopefully somewhere down the road, when I'm not around – way down the road – our community becomes an educated community. And they will look back to that time when a few stepped up – like ASU – and helped us.”

San Carlos Apache College is currently a two-year college. Rambler said the goal is for the school to have its own bachelor's degree program someday, linked to ASU.

And his hopes extend beyond the classroom.

“Someday, hopefully the environment will be better where we can create our own San Carlos Apache College basketball team,” he said. “I can't wait for that day.”

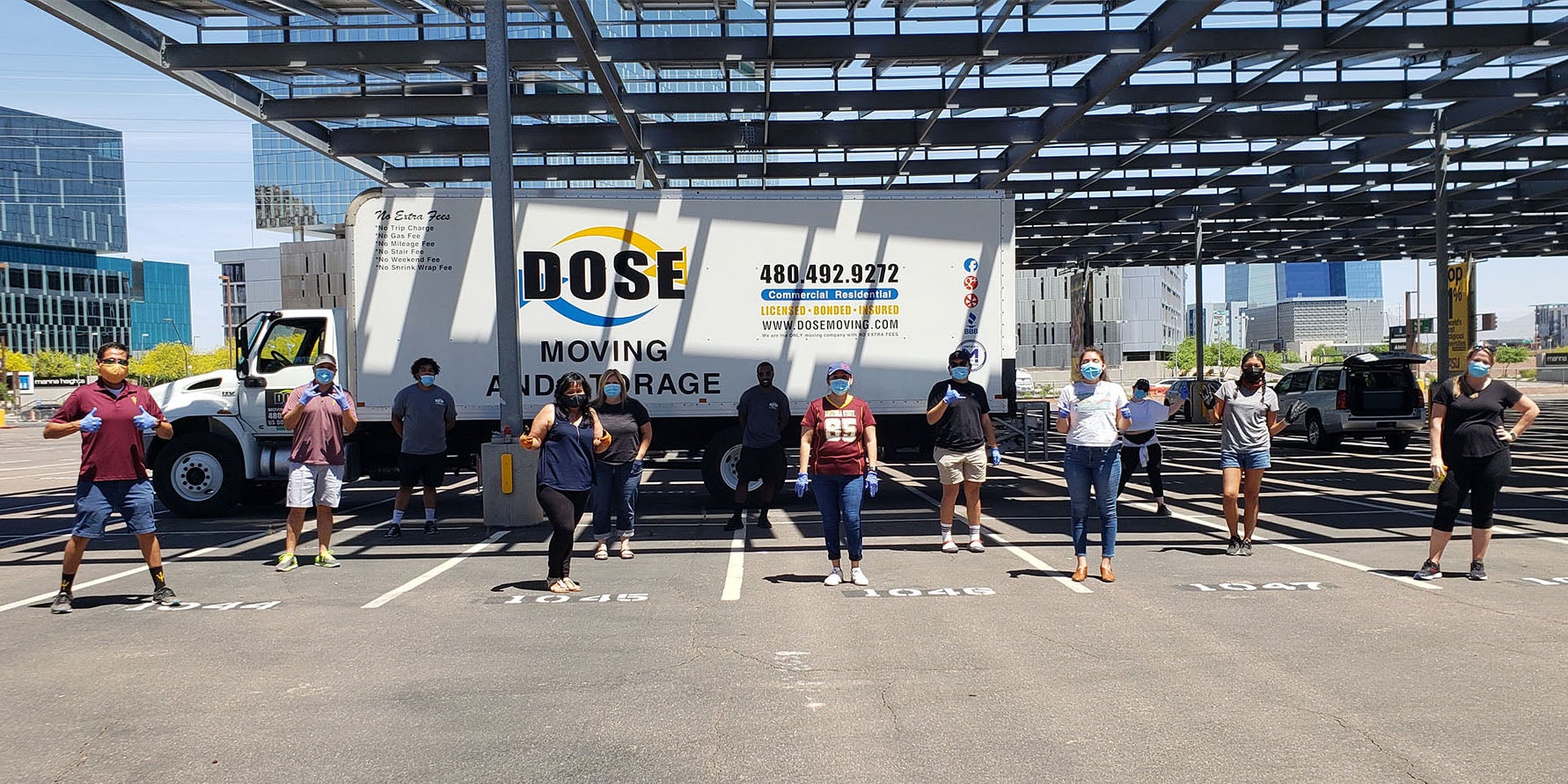

Over the summer, a team of ASU alumni instituted the First Peoples’ COVID-19 Resource Drive, an initiative to deliver much-needed supplies to tribal communities struggling with the impact of the pandemic. They sent emergency supplies Navajo, Hopi, Hualapai, Havasupai and White Mountain Apache communities.

“Initiatives like the First Peoples’ Drive assist tribal governments and agencies with relief efforts,” said Marcus Denetdale, program director for ASU’s Construction in Indian Country program. “In this case, the supplies went from Sun Devil Stadium to tribal doorsteps in three days or less.”

Volunteers for the First Peoples’ COVID-19 Resource Drive line up near the Sun Devil Stadium on ASU's Tempe campus before the drop-offs begin on May 7. Photo by Marcus Denetdale/ASU

The university has also provided to tribal communities COVID-19 test kits, testing research, medical and public health support, and PPE supplies. In the upcoming months, Ignacio of the School of Social Work will be traveling to various reservations to discuss the efficacy and safety of a COVID-19 vaccine. He doesn’t know if he can talk reluctant members into taking the vaccine, but he does know the door is always open for discussion.

“That relationship is there, and that’s a necessary part of being engaged with the community,” Ignacio said. “ASU’s attitude has always been, ‘Let’s make this a win-win situation and create positive change.’ Wherever the need is, I’m willing to help.”

That willingness to help is what makes ASU stand out in the field of American Indian studies, said Teresa McCarty, the G.F. Kneller Chair in Education and Anthropology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“In many respects it’s not surprising that ASU has realized these milestones,” McCarty said, who is a member of the National Academy of Education. “All of this is a credit to ASU, but it is equally a testimony to the committed efforts of Native nations, communities and individuals who have reached out to ASU to build partnerships and offer their expertise. It is heartening to see the fruits of these reciprocal tribal-university investments reflected in ASU’s enrollment and degree-conferral milestones.”

These community ties, the record numbers of enrolled students and the fact that ASU is producing PhDs, lawyers, judges, nurses, artists, CPAs, chemists, social workers and educators — all of it brings a smile to Zah’s face. It's a far cry from when he was one of just 17 Indigenous students on campus.

“What does it do to my heart … the fact that ASU is the No. 1 educator of Native Americans?” Zah said. “Well, it makes me feel good and it’s something to be proud of. There’s a lot of joy in that statement, and I’m very, very happy.”

Infographic by Alejandro Cabrera Ramirez/ASU

Top photo: Air Force veteran Janilda Garnier receives her hood from Clinical Professor Andrew Carter for earning a Master of Legal Studies at the Sandra Day O'Connor College of Law Convocation at the former Comerica Theatre, on May 10, 2017. She is a member of the Navajo Nation.