In the latest installment of Health Talks: COVID-19 Series, the Arizona State University College of Health Solutions’ series of talks on issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, moderator Matthew Scotch, an associate professor of biomedical informatics, welcomed Executive Director of the Biodesign Institute Joshua LaBaer and Professor David Sklar to discuss everything from the recent history and development of human coronaviruses to the current diagnostic challenges and methods of combating COVID-19.

The health talks are free, available for continuing education credit and open to anyone seeking information and knowledge while navigating the current health crisis. The COVID-19 series in particular is offered virtually and features experts from a variety of backgrounds on topics including causes of the virus, how scientists use biomedical data to make data-driven decisions and how to maintain well-being and health while sheltering at home.

The next talk in the series, “Health Information and Misinformation During COVID-19: What Can We Believe?” will take place at noon, Thursday, Oct. 22, and will feature Clinical Assistant Professor Swapna Reddy, Managing Director of the Cronkite School’s News Co/Lab Kristy Roschke, and Dr. Quinn Snyder, an emergency medicine physician at Banner Desert Medical Center.

On Thursday, Sept. 17, the day of the talk titled “From Bench to Bedside in the COVID-19 Era: The Role of Testing in Clinical Care and Public Health Surveillance,” Scotch noted in his introduction that the state of Arizona reported about 1,700 new cases of the virus, according to the Arizona Republic.

“(That) represents an increase from the downward trends that we’ve seen over the last few weeks,” he said.

LaBaer was the first to present, beginning with a brief history of human coronaviruses, which began with mild to moderate upper-respiratory tract illnesses in the 1960s, followed by the emergence of SARS in 2002, MERS in 2012 and now SARS-CoV-2.

“I always say that this virus won the virulent virus trifecta, because it has three characteristics that make it such a devastating virus for humankind,” LaBaer said of SARS-CoV-2.

Those characteristics are: severity, spread and stealthiness. Severity because of its high morbidity and mortality rate (10 times worse than the flu); spread because it is capable of airborne transmission; and stealth because the peak of infectivity is when the individual is still presymptomatic.

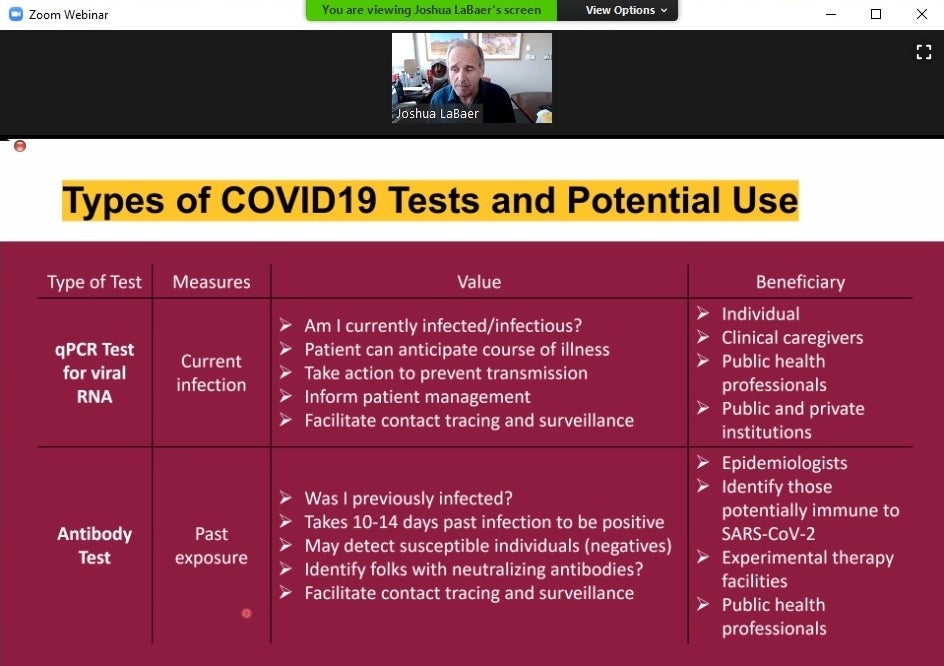

Currently, two types of tests exist for the coronavirus: the qPCR test for viral RNA, which determines whether someone is presently infected, and the antibody test, which determines whether someone had past exposure to the virus.

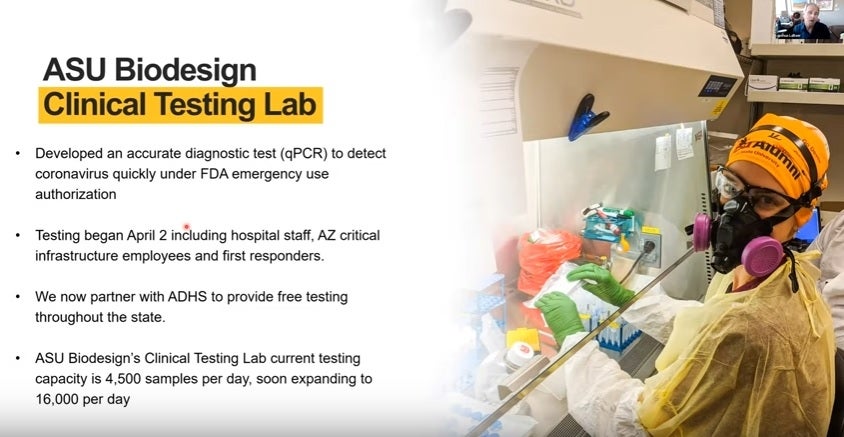

As early as March, LaBaer and researchers at ASU’s Biodesign Institute began meeting to develop a system for testing for the virus at the university. At that time, there were very few tests being done in the state of Arizona – only about a couple hundred nasal swab tests, according to a poll they conducted with hospitals.

“We realized as a university, we were uniquely capable of setting up this sort of operation, because we had the skill sets, we had the technology. … We know how to do this, let’s do it,” LaBaer said.

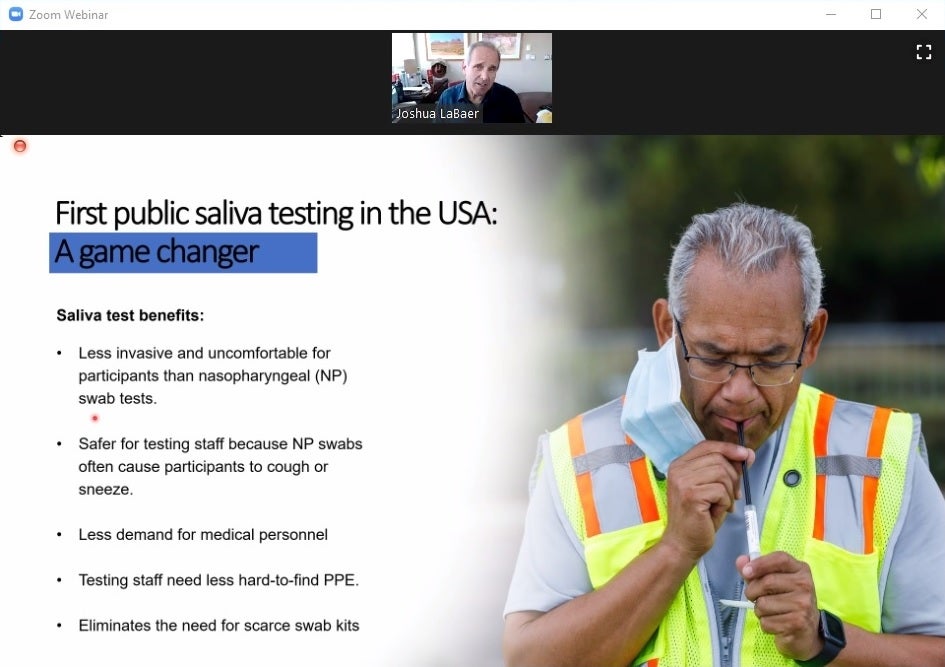

Today, ASU Biodesign’s Clinical Testing Lab runs more than 4,000 tests a day, with plans to expand to 16,000 per day. Much of that is possible because researchers there were the first in the state to develop and offer saliva-based testing to the public, greatly expediting the testing process.

Biodesign researchers are also conducting contact tracing and have made a website available to the public that tracks epidemiological data for the state.

“A lot of people regard our site as one of most reliable sites for providing data about the pandemic in the state of Arizona, and we’re quite proud of that,” LaBaer said.

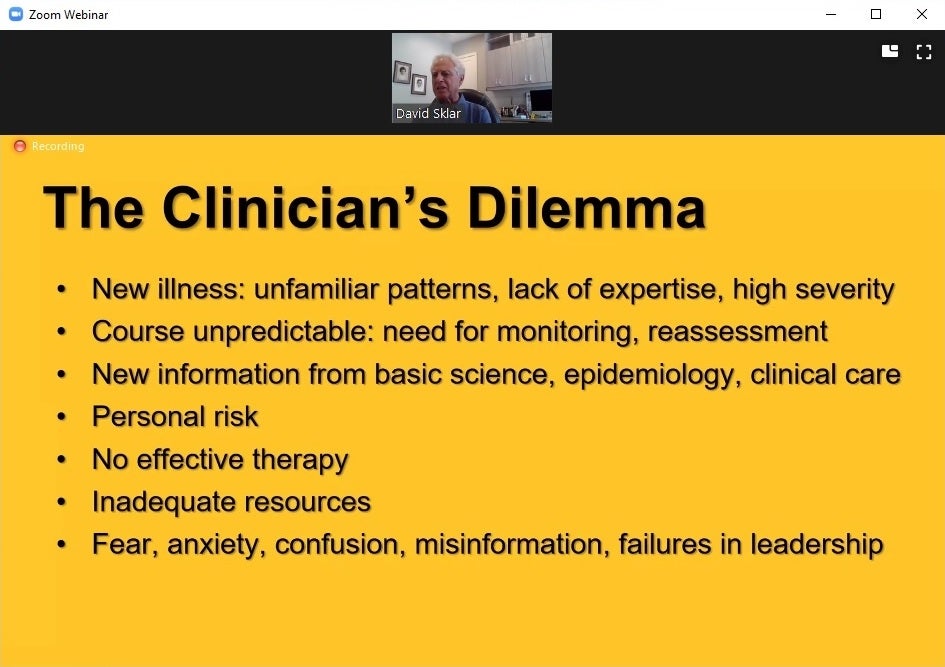

Much of Sklar’s presentation focused on the challenges physicians are facing in diagnosing and treating the virus.

“This disease, as well as being very new and complex and interesting, has a variety of clinical implications,” he said. “Unfortunately, the clinical information is just getting almost overwhelming in terms of keeping up with it.”

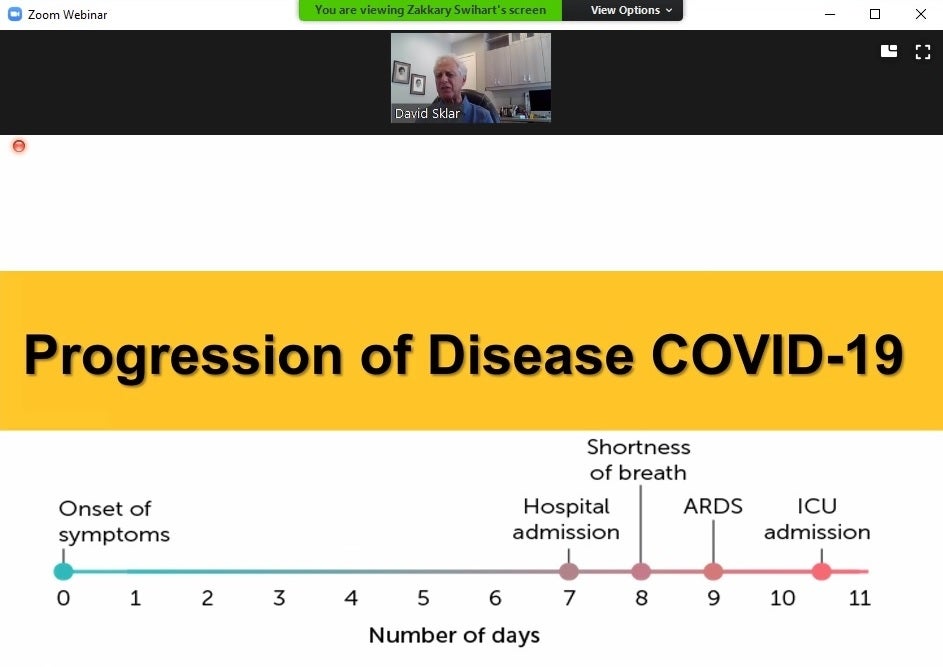

Reasons for that range from the variety of symptoms to the unpredictable nature of its progression. The majority of cases, 81%, are mild; 14% are severe; and 5% are critical – the problem is there is no way to predict who will be among the 81% and who will be among the 5%.

The difficulty associated with diagnosing the virus based on a physical exam alone underscores the importance of the kind of testing being done by the Biodesign Institute and other organizations, Sklar said.

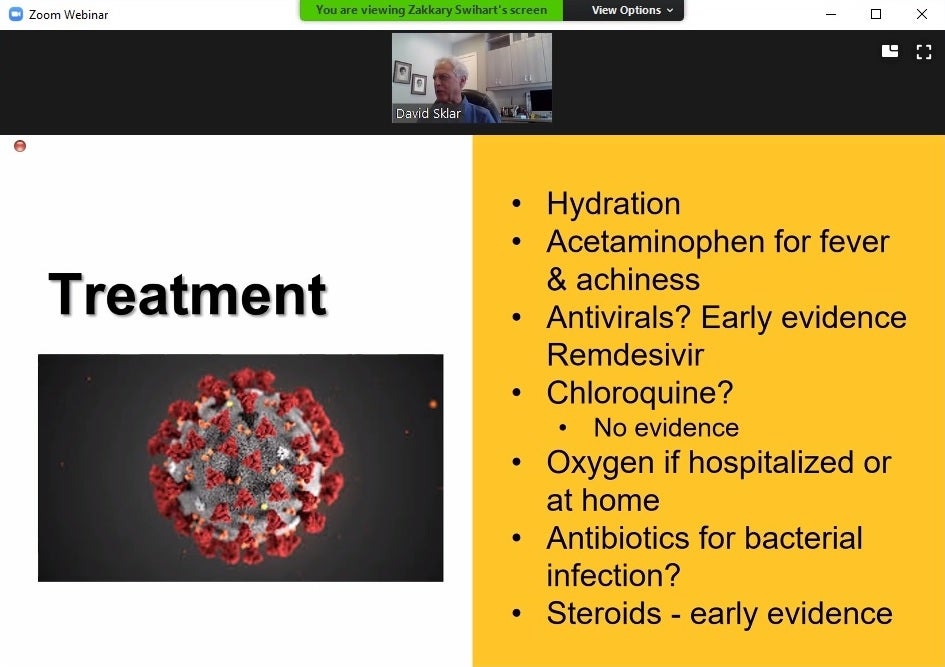

As far as treatment, there are some things that seem to remain consistently effective, such as hydration, and the use of steroids seems to be promising at the moment. However, Sklar said, “What I’m telling you today may not be true tomorrow.”

That has been the case with ventilators, used heavily and often at the beginning of the pandemic, health care workers are now finding that they can sometimes worsen the situation by causing injury to the lungs.

“Vaccination, of course, is the million dollar question,” Sklar said. “Will we have a vaccine? Most likely, we will. What will it cost? We don’t know. Who will have access? Most likely it will be people either in the health care provider group or people who are at highest risk. Will it be safe? That’s again, one of the million dollar questions."

Sklar noted that there has always been some fear of and resistance to vaccines, even when their safety was fairly well-proven, such as measles vaccines. Those attitudes may be due to instances in the past, as with the swine flu vaccine, where some who received it experienced complications, though Sklar added that it was a very small number of people in that case.

During the Q&A portion of the talk, Professor Scott Leischow, College of Health Solutions director of clinical and translational science, asked whether continued improvements in managing symptoms would be sufficient enough to get society back to a state of normalcy while we wait for a vaccine.

“We really want to stop the spread; we don’t want to be operating at the level of managing symptoms,” LaBaer said, adding that prevention is key because of how much we still don’t know about the virus, including whether asymptomatic people can suffer long-term effects.

“The virus has not even been in the human population a full year yet, so long-term studies are impossible,” he continued. “But we do know there are plenty of viruses out there that can cause cancer over time, that can cause neurological disease over time, that can cause all kinds of long-term health sequelae … and we just simply don’t know in this case what getting this virus does. So the best thing you can say is — don’t get it.”

And the best way to not get it is to continue doing what we already have been: wearing masks, socially distancing, staying home and getting tested if your work or life circumstances require you to interact with the public often.

Top photo: Screenshot of Biodesign Institute Executive Director Joshua LaBaer's PowerPoint presentation for ASU's College of Health Solutions COVID-19 Health Talk series, featuring the faces of researchers at ASU Biodesign’s Clinical Testing Lab.

More Health and medicine

PhD student builds bridges with construction industry to prevent heat-related illnesses

It is no secret that Arizona State University has innovative researchers working to help solve everyday problems.According to a new preliminary report issued by Maricopa County, there were more…

Working to cure cancer in our lifetime

What if we could cure cancer, or come close, in our lifetime?That’s a goal that researchers at Arizona State University’s Biodesign Institute have dedicated years of time and resources to, so that…

10 companies, 5 nations, 1 accelerator: A wide range of innovative health care solutions

The 10 companies participating in the 2025 Mayo Clinic and ASU MedTech Accelerator program hail from five different nations and are the first cohort to have representation from life science companies…