New data unveils ancestry of first peoples to inhabit Caribbean

A map of the Caribbean showing the location of the sites discussed in the research and the number of individuals analyzed per site. Squares represent sites with samples from Archaic-related contexts while circles denote Ceramic-related contexts. Date ranges for each site are reported below. Reprinted with permission from K. Nagelä et al., Science 10.1126/science.aba8697 (2020).

Researchers now have a better understanding of how the first people moved to and through the Caribbean. A new study published in Science recognizes at least three migrations of ancient people through the islands. Two early groups came to present-day Cuba from the mainland, and one came to what is now Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles from South America.

These discoveries came from analyzing 93 ancient Caribbean DNA samples spanning a time frame from 3,200 to 400 years ago. Samples were obtained with permission from excavations or existing collections of museums and universities.

Arizona State University researchers from the School of Human Evolution and Social Change contributed data and analysis from Puerto Rico. Anthropological geneticist and Regents Professor Anne Stone supervised the work of Maria Nieves-Colón, a doctoral student at the time and now a research affiliate of the school.

Nieves-Colón originally analyzed ancient Puerto Rican islander DNA during her graduate studies, publishing findings in Molecular Biology and Evolution. Researchers from the University of Copenhagen invited Nieves-Colón to collaborate on this larger study analyzing the ancestry of the Caribbean region.

From the mainland

Historically, it has been unclear how and from where the first inhabitants of the islands arrived. Archaeologists have offered multiple theories based on pottery and other artifacts, but this study links together genetic data in a new way and provides a more detailed understanding of human movements in the area.

The first two migrations, during what is known as the Archaic Period, spanned approximately 3,000 to 1,000 years ago. The third major movement happened during the Ceramic Period when researchers saw evidence of elaborate ceramics being introduced to the Caribbean. The Ceramic Period occurred between 2,500 and 500 years ago.

To better analyze the actual movement of early peoples to and through the islands, researchers compared ancient DNA from specific sites in the Caribbean to DNA found at other sites around the world for similarities. Evidence from the first migrations suggests an early colonization of present-day Cuba from the mainland. Although the precise origin of this migration is unclear, one ancient individual sampled from Cuba shares ancestry with ancient populations who lived on the California Channel Islands. Later migrations, during the Ceramic Period movement, saw people travel up from South America to Puerto Rico and the Lesser Antilles, according to the study.

Researchers were surprised to find that the waves of settlers seem to have kept their distance from each other.

“We would have expected to see that people who came after would have had a mix between the DNA of the early and later settlers, but we didn’t see that,” Nieves-Colón said.

Researchers do not know why this was the case, but more data would likely provide additional insights.

While the researchers found evidence of these three movements, Nieves-Colón cautions that people may have been in parts of the Caribbean even earlier. DNA analysis of older remains is often difficult.

Nieves-Colón used equipment in ASU’s ancient DNA lab to extract DNA from skeletal remains from Puerto Rico.

While the hot and moist environment of the Caribbean is not conducive to preserving ancient DNA, advances in technology over the last decade have led to increased accuracy and the ability to extract more DNA from a single sample. Looking at more and longer sequences of DNA provides results with higher levels of confidence.

Maria Nieves-Colón prepares a tooth for DNA extraction. Photo courtesy of Maria Nieves-Colón.

Ethical, collaborative science

Stone and Nieves-Colón worked with archaeologists, agencies and the Puerto Rican Institute of Culture to obtain permission to conduct the research.

“When we work with ancient DNA, unfortunately, it’s generally a destructive process, so we are careful to complete the work ethically,” Nieves-Colón said.

She and her collaborators took extra steps as researchers cognizant of their work, including sending permission-granting institutions copies of the finished papers and returning remains that are intact after DNA extraction.

As a Puerto Rican, Nieves-Colón said, “It’s important for me to do this research right because they are my ancestors, too.”

Nieves-Colón is continuing her research on Puerto Rican DNA. She is interested in understanding the relationship between the ancient people of Puerto Rico and the people living there today.

“There’s been a narrative of the Native Americans in the Caribbean going extinct,” Stone said. “What you see in the DNA is that that’s not true, they exist, but they are mixed into the population today.”

The work for Nieves-Colón’s dissertation was funded by the National Science Foundation, the Rust Family Foundation for Archaeological Research and the School of Human Evolution and Social Change.

More Arts, humanities and education

AI literacy course prepares ASU students to set cultural norms for new technology

As the use of artificial intelligence spreads rapidly to every discipline at Arizona State University, it’s essential for…

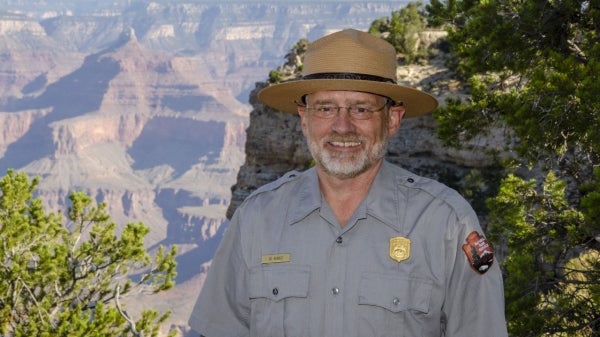

Grand Canyon National Park superintendent visits ASU, shares about efforts to welcome Indigenous voices back into the park

There are 11 tribes who have historic connections to the land and resources in the Grand Canyon National Park. Sadly, when the…

ASU film professor part of 'Cyberpunk' exhibit at Academy Museum in LA

Arizona State University filmmaker Alex Rivera sees cyberpunk as a perfect vehicle to represent the Latino experience.Cyberpunk…