Pioneering ASU Regents Professor reflects on legacy after 57 years at university

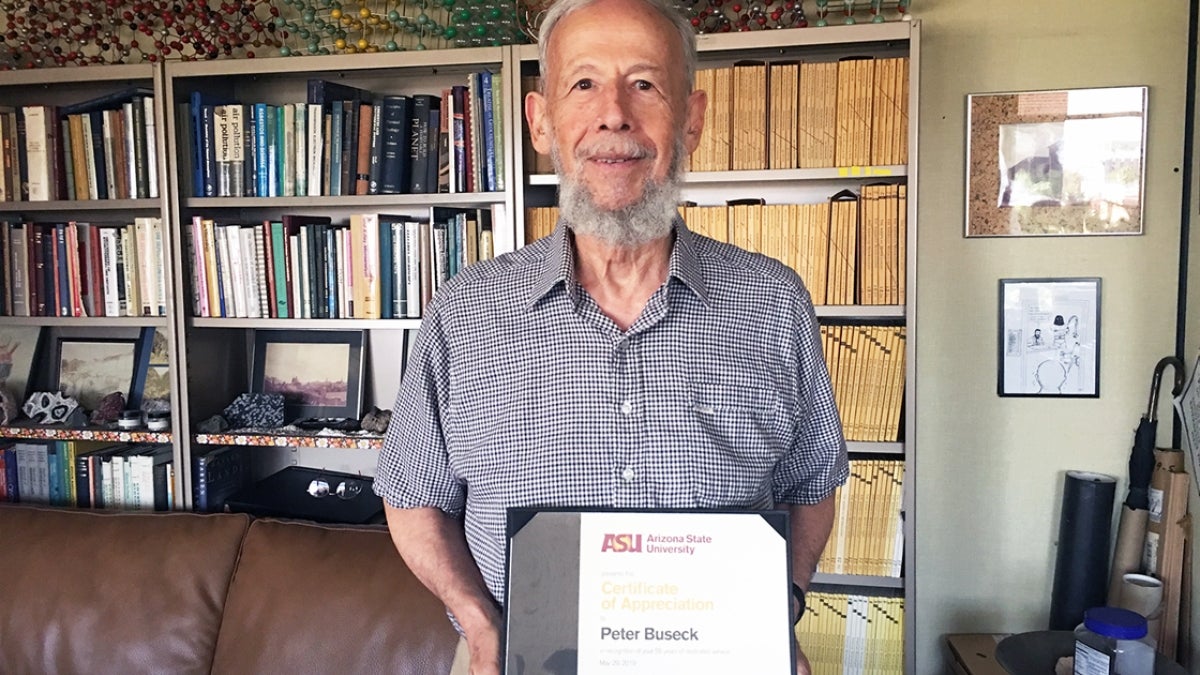

Peter Buseck received recognition of his 55 years of service from ASU President Michael Crow. Photo by Mary Zhu/School of Molecular Sciences

Regents Professor Peter Buseck is a pioneering researcher who continues to inspire, even after almost 60 years of service at Arizona State University.

Buseck graduated from Columbia University in 1962 with a PhD in geology and began teaching at ASU in 1963.

At that time, the price of a stamp was $0.04, a gallon of gas was $0.29, and the average price for a new house was around $15,000. With a starting annual salary of $7,400, Buseck began his career as an assistant professor with a dual appointment in both the geology and chemistry departments.

Buseck reflects, “I remember my dad telling me that I would probably never earn $10,000 per year in academia, whereas I would be financially more secure if I joined him in business. It took me several years to achieve an annual salary of $10,000, but even before doing so, my wife, Alice, and I managed to live modestly but adequately.”

Buseck's dual appointment was a surprise to him. He knew he had been hired by the geology department (today the School of Earth and Space Exploration), but upon arrival discovered he would also be in the chemistry department (today the School of Molecular Sciences), which at the time was chaired by LeRoy Eyring. This additional appointment happened because ASU’s newly acquired meteorite collection was housed in chemistry and Peter would be using it for research.

“I was never asked, but that is how I became a professor of chemistry. Having a position in the chemistry department is one of the strange but fortunate accidents that can occur from time to time,” Buseck said.

Being part of two departments enabled Buseck to study phenomena from several perspectives, giving his research an interdisciplinary character at a time when collaborations between departments were rare. In addition to chemistry and geology, he forged relationships with colleagues in physics. Buseck’s cross-cutting approach to science, coupled with novel high-resolution electron microscopy, soon paid off.

“Students and postdocs in my group almost routinely had their results published in Science, Nature and the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, sometimes more than once per year, and commonly with cover photos," he said. "Considering how hard we struggled in subsequent years to have papers appear in those journals makes me realize just how special that time was. We were riding the wave crest of discovery.”

Buseck’s research primarily involved the application of transmission electron microscopy (TEM) in four major areas: minerals, meteoritics, fullerenes and related carbon phases, and atmospheric chemistry. Air pollution was a severe problem in Phoenix in the 1960s. Using ASU’s first electron microprobe, Buseck and PhD scholar John Armstrong obtained the first quantitative chemical analyses of airborne particles.

“Thus,” Buseck said, “started my entry into atmospheric chemistry, subsequently sustained by outstanding colleagues that include, among others, PhD students Gary Aden, Jeff Post, Li Jia and John Bradley, and postdocs Mihály Pósfai, Tomoko Kojima and Kouji Adachi.”

Buseck was also instrumental in growing ASU’s solid-state science program. With colleagues LeRoy Eyring, Michael O’Keeffe and Galvin Professor of Physics John Cowley, along with his research associate Sumio Iijima (who later discovered carbon nanotubes), Buseck launched the nascent field of high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) of minerals.

They, together with physics postdocs Mike O’Keefe and Peter Self, demonstrated that crystal structures — which at the time could only be deduced theoretically — could now be imaged directly. From these results, collaborations developed with Harvard professors Charlie Burnham and Jim Thompson, and postdoctoral researcher David Veblen, “beginning a long and productive collaboration and friendship that lasts to this day,” Buseck said. Veblen’s PhD students Huifang Xu and Jun Wu, currently at ASU, became Buseck postdocs, so the connections continue.

Buseck's research group also studied meteorites, performing some of the earliest mineralogical research on a class of meteorites that contain carbon, called carbonaceous chondrites. These meteorites are important for their connection to the origins of life. By utilizing HRTEM, Buseck — along with postdoc Kazu Tomeoka, and later Lindsay Keller, Donald Eisenhour, Hua Xin, Laurence Garvie, Dante Lauretta, Tom Zega and many other talented young scientists — was able to obtain mineralogical details that had been impossible to obtain by existing methods.

Over the decades, Buseck built a diverse research group that has included students, postdocs and visiting scientists from 25 countries and six continents. Under Buseck’s talented mentoring, this group has produced over 450 papers that have been cited nearly 26,000 times, with 80 of these papers being cited at least 100 times, yielding a Google Scholar h-index of 91. Google scholar also reports Buseck as the No. 1 most cited meteoriticist and the No. 6 most cited mineralogist.

Nature recently hailed a 1978 Buseck article on the high-resolution imaging of crystal structures using transmission electron microscopy as a milestone in crystallography.

Buseck’s grants and other awards have brought in over $31 million from the National Science Foundation, National Aeronautics Space Administration and the U.S. Department of Energy, among others.

Buseck shows no signs of slowing down. In 2016, Buseck won a prestigious Keck Foundation Award as the principal investigator to study the origin of Earth’s water. Then, in 2018, he won a second Keck Foundation Award as a co-investigator to study a chainlike form of carbon, called pseudocarbyne.

In 2019 Buseck was awarded the Roebling Medal, the highest award of the Mineralogical Society of America, for outstanding original work in mineralogy. The award was presented at the annual Geological Society of America conference, where a special session on minerals at the nanoscale was held in his honor. Many of his former students and postdocs, plus others who worked with him, attended and participated.

Peter Buseck was awarded the 2019 Roebling Medal by the Mineralogical Society of America. From left: 2019 MSA President Mickey Gunter, Buseck, Mihály Pósfai and 2020 MSA President Carol Frost.

The impact and quality of Buseck’s career and character are seen not only in the awards and recognition he has received, which are numerous, but also in the achievements of his former students.

Jeff Post — curator of the Smithsonian’s U.S. National Gem and Mineral Collection, including the Hope diamond, since 1991 — was awarded the Lifetime Achievement Award by the Jewelers of America. Mihály Pósfai is a member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Sumio Iijima is, among a long list of honors, a member of the U.S. National Academy of Science, as well as those of Japan, China and Norway.

Iijima, John Armstrong, Mike O’Keefe and David Veblen have all served as presidents of professional societies. Ellen Thomas received the 2013 American Women Geoscientists Professional Excellence Award. Kouji Adachi was awarded the Young Researchers' Award from the Japan Association of Aerosol Science and Technology (JAAST) in 2016.

Also in 2016, Mihály Pósfai won a Széchenyi Prize, which is awarded to “the greatest Hungarian minds alive today.” It is “the most prestigious state award in the sciences” and was given in a ceremony led by the president and the prime minister of Hungary. These researchers, and many others not named here, are all part of Buseck’s legacy to science and scholarship around the world.

Peter Buseck's former students and postdocs attended a 2012 dinner honoring Buseck, held during a two-day symposium that honored his career contributions at the 2012 Microscopy and Microanalysis Meeting. Front: Jun Wu, Joe Goldstein, Steve Lehner, Dawn Janney, Shirley Turner, Peter, Barbara Minor, Ed Holdsworth, John Armstrong. Back: Tom Sharp, Mihály Pósfai, Susan Lowry, Rafal Dunin-Borkowski, Roy Christoffersen, Tom Zega, Craig Johnson, Lindsey Keller, Laurence Garvie, Heiner Friedrich, Péter Németh, Taiga Okumura, Mike O'Keefe.

In Arizona, three of his students and postdocs have followed in his footsteps. Tom Sharp is a professor in the ASU School of Earth and Space Exploration and associate director of the Arizona Space Grant Consortium. At the University of Arizona, Professor Dante Lauretta and Associate Professor Tom Zega conduct research at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

Buseck is quick to recognize that his achievements were not accomplished in isolation. He points out that the efforts of the many people in his research group over the decades have made it possible for him to be where he is today.

“I especially want to recognize LeRoy Eyring, who started out as my boss, but we became very good personal friends. He was welcoming and kind,” Buseck said.

He also wishes to recognize colleague John Cowley: “He was extremely kind and generous with his time. He was always patient, and very helpful.”

These qualities are evident in Buseck as well, and they helped him develop and maintain a research group that has been highly productive over almost six decades. When asked for what he would like to be remembered, he replied without hesitation, “For being a good husband and father.”

Buseck was married for over 50 years to his wife, Alice, before she passed away. Together they had four children.

He now has five grandchildren and is an active part of their lives, passing on to them the wisdom he has gained over his career.

“No matter what path you follow, you must always retain personal values and remember those things that you find truly important in your life and in those around you," Buseck said. "Most important is to think freely and creatively; maintain a vibrant curiosity about all things; don’t be too impatient; and get a good education so you are prepared to tackle whatever opportunities or new ideas that come along.”

More Science and technology

Statewide initiative to speed transfer of ASU lab research to marketplace

A new initiative will help speed the time it takes for groundbreaking biomedical research at Arizona’s three public universities…

ASU research seeks solutions to challenges faced by middle-aged adults

Adults in midlife comprise a large percentage of the country’s population — 24 percent of Arizonans are between 45 and 65 years…

ASU research helps prevent substance abuse, mental health problems and more

Smoking rates among teenagers today are much lower than they were a generation ago, decreasing from 36% in the late 1990s to…