Three women, three countries and hundreds of letters spanning five decades.

Nearly a century later, three more women — also from three different countries — and hundreds of hours of painstaking sleuthing, transcribing, dating and translating.

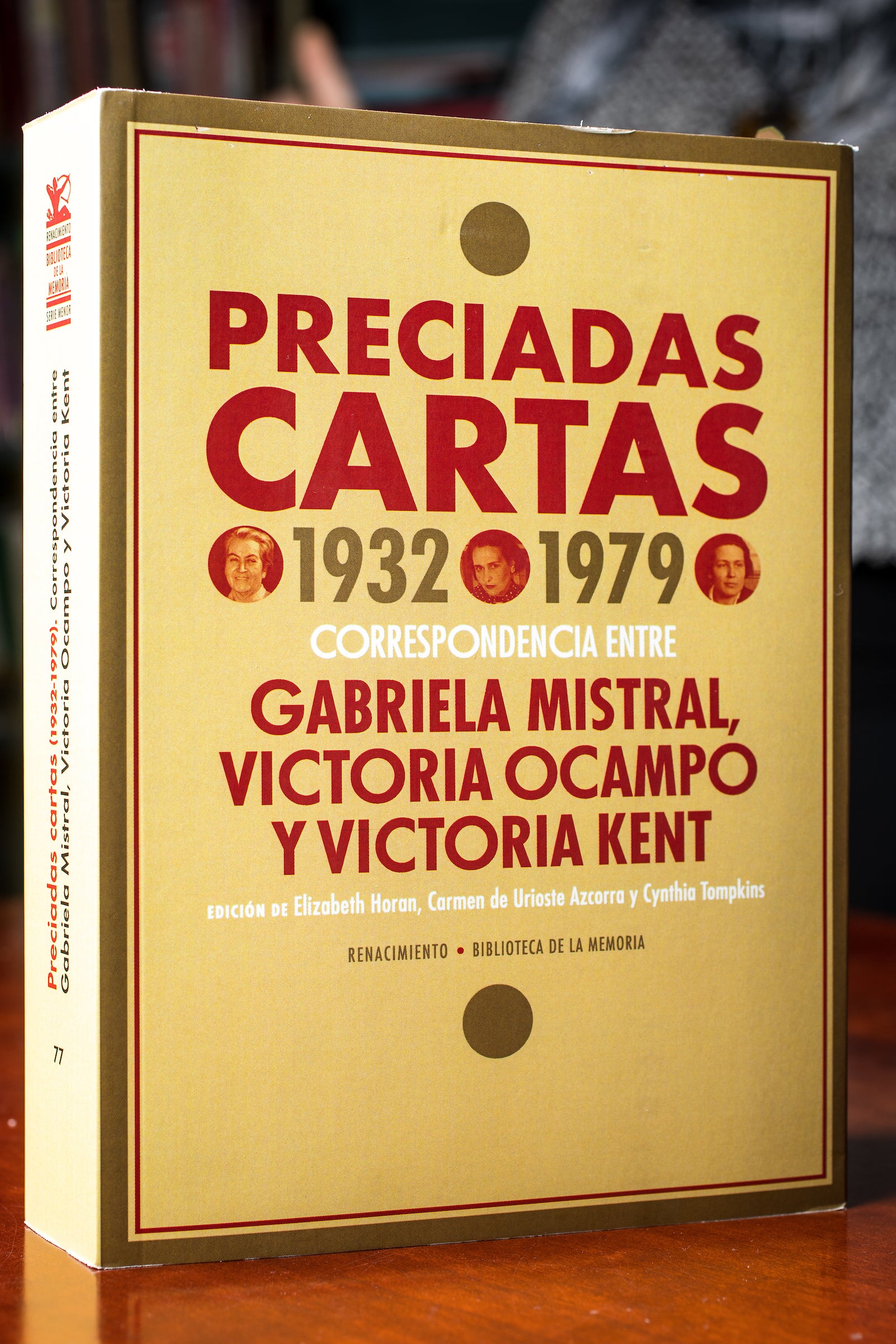

These are the basic elements of “Preciadas Cartas (1932-1979),” a collection of deeply revealing letters between Chilean poet-diplomat Gabriela Mistral, Spanish lawyer and politician Victoria Kent and Argentine writer and intellectual Victoria Ocampo.

But there are also dashes of political intrigue, profound ruminations on the sociocultural issues of their time and tender reminiscings, all bound together by an uncommon yet uniquely powerful friendship.

In many ways, the women who wrote these letters were dissimilar. They each came from varying personal and educational backgrounds, belonged to different social classes and pursued diverse professions. However, in many ways, they were also very similar. All three were writers, liberals and feminists who rejected the conventional lifestyles expected of them.

Though they were influential public figures during their lifetimes, on a larger historical scale, their memory has since begun to fade into obscurity. In “Preciadas,” the travails, accomplishments, hopes and desires of these powerhouse Spanish-speaking women are resurrected anew, as their letters — most of which have never been published before — illustrate the fortitude and devotion that instructed their lives during the years of uncertainty and upheaval of the Spanish Civil War and subsequent Franco regime.

Proof positive

For years following their deaths, the letters between Mistral, Kent and Ocampo were only rumored to exist — whispered suspicions among scholars. Then in 2011, Arizona State University Professor of English Elizabeth Horan received a letter from highly regarded Cuban scholar Carlos Ripoll. He had the letters, he told her, and he was looking to sell them. He contacted Horan because of her previous work on the Gabriela Mistral archives and publications of some of her other letters.

Horan was intrigued. “These three women were arguably the most influential women of their countries, and really of the time, in the Spanish-speaking world,” she said. But she wanted proof. Ripoll responded with some photocopies and a detailed account of how he came into ownership of the letters:

Shortly after the death of Kent (the last of the three women to pass away) in 1987, her secretary and lover Louise Crane reached out to Ripoll saying she had more than 200 of the fabled letters and asked him for help transcribing and publishing them. Many of the letters were undated, a challenge that Ripoll tried but was unable to overcome. Now he was ready to pass the torch.

Based on the handwriting and contents of the letters, as well as Ripoll’s compelling explanation, Horan was convinced of their authenticity. But before she could respond, he died.

The fate of the letters now uncertain, Horan immediately contacted the head of special collections at Florida International University in Miami, where Ripoll had begun a collection, and explained about the letters and their value. They said they would look into it, and that was the last she heard for two years, until she saw on their website that they had added to the Ripoll collection.

So in 2013, Horan headed to Miami to have a look in person. What she found was an obviously incomplete collection of the letters, most of which were photocopies. No one could tell her where the originals had gone.

Ever persistent, Horan put on her detective hat and eventually discovered that Ripoll had given some of them to the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale, and some others to the Houghton Library at Harvard. The rest she knew to be in the Mistral archive in Chile, thankfully already digitized.

Dream team, assemble

After tracking down and photographing all of the letters, Horan began attempting to arrange them by date. But the sheer scope of the task was daunting.

So she called for reinforcements: two of her closest friends and colleagues, Carmen Urioste-Azcorra (a native of Spain, like Kent) and Cynthia Tompkins (a native of Argentina, like Ocampo), both professors of Spanish at ASU’s School of International Letters and Cultures. (Horan, though a native of the United States, rounded out the eerie parallel to the elder trio with her strong ties to Mistral’s native Chile, a place she had both spent time studying and whose poets, especially Mistral, she was fascinated by.)

From left to right: ASU Professor of Spanish Cynthia Tompkins, Professor of English Elizabeth Horan and Professor of Spanish Carmen Urioste-Azcorra. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

Horan scheduled a meeting with Urioste-Azcorra and Tompkins, but didn’t mention anything about the letters.

“I remember I said, ‘We're going to have lunch,’” Horan said. “I didn't say what it was about. And I described the letters, and I said, ‘Victoria Kent,’ and Carmen sat up and went (Horan mimes an open-mouthed expression of shock) like that. And then I said, ‘Victoria Ocampo,’ and then I mentioned Mistral, and then it was pretty clear from that point where I was going with it.”

While Urioste-Azcorra was instantly on board, Tompkins needed some convincing.

“Ocampo’s acceptance in Argentina was ... people were very divided in terms of her contributions,” Tompkins said. “Some just saw her as a frivolous woman who went to Europe and had the money to consort with the intelligentsia of the time. Others saw her as a feminist. So I thought, ‘Hmm... What's new here?’ I was very leery.”

What changed her mind was the content of the letters. According to Tompkins, Argentines knew of some of Ocampo’s contributions to human rights: that she had saved some Jews from concentration camps during the Holocaust, for instance.

“But I didn’t know the extent to which she had collaborated in these ventures,” Tompkins said. “And that comes out very clearly in these letters.

“It gave me a political perspective that I was unaware of. (Ocampo) had been, like Kent to an extent, against awarding the vote to Argentine womenVictoria Kent opposed giving Spanish women the right to vote without them having received the proper social and political education needed to vote responsibly, fearing their vote would be influenced by Catholic priests and end up damaging left wing parties.. But she had also been a political prisoner. So she had a very contested legacy. But what made her more human to me was the veiled references to illness. She had cancer; she had it for a long time. And that was very hard to see. And people in Argentina usually do not mention that. So that made her much more likeable, much more human.”

Horan was relieved when Tompkins, too, joined the ranks, and her dream team was complete.

“I was really afraid that if I could find these letters, someone else could find them,” Horan said. “And that someone else would botch it up, and just write all this stuff that wasn't true and that was overly sentimental. And I knew that Carmen and Cynthia would also be concerned that it be accurate.”

Like Mistral, Kent and Ocampo before them, the three professors had been friends for decades, having all crossed paths in academia at one point or another. When all of them are in a room together, laughter is abundant and the sense of easy camaraderie is contagious. Even after “Preciadas” has been published, they still squabble over minute details: How many times did Mistral, Kent and Ocampo actually meet in person? (They learned of each other through mutual friends and began corresponding before meeting face-to-face.) It was less than one would expect given the length of their friendship, but it was still hard to pin down.

As the professors sit in an office on ASU’s Tempe campus trying to recall the various instances of the women’s meetings, Horan explains how she feels that because Mistral lived at Ocampo’s house for three months at one point, it counts as more than a single occasion, while Tompkins feels otherwise.

“You see?” Tompkins exclaims. “Here we go again!”

Boisterous guffaws erupt from all three, and Urioste-Azcorra jumps in to mediate, saying, “Well, we are in agreement that it was around eight meetings for Ocampo and Mistral, and around 12 for Ocampo and Kent.”

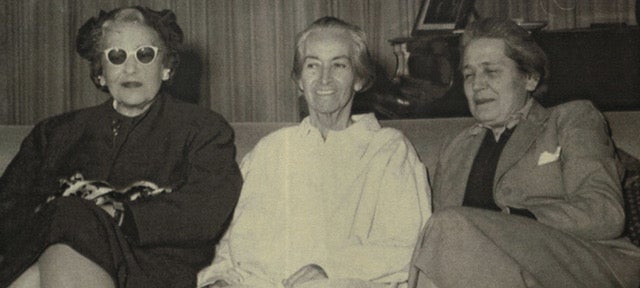

Left to right: Argentine writer and intellectual Victoria Ocampo, Chilean poet-diplomat Gabriela Mistral and Spanish lawyer and politician Victoria Kent.

Putting the pieces together

Over the course of two years, Horan, Urioste-Azcorra and Tompkins worked their way through roughly 600 pages of correspondence. It was no small task.

Urioste-Azcorra had to purchase a projector to enlarge Kent’s handwriting to make it more legible, but still there were difficulties. Once she knew what a typical Kent “a” looked like, for example, she was able to compare it to an otherwise indecipherable word to determine whether it contained an “a.” If it did not, she tried another letter. And on and on.

Tompkins had somewhat of an easier time with Ocampo’s letters, most of which were typed. However, they too presented a quandary, with myriad handwritten notes and addendums scrawled up, down and around the margins.

Dating the letters was another beast entirely. But thanks in large part to Mistral’s undying wanderlust (Horan said she “moved more often than most people change their clothes”), the professors were able to cross-reference where she was living at the time with historical events described in the letters to figure out the proper chronological order.

Horan described the experience as being akin to a puzzle.

“When you have the majority of the letters reliably dated, it makes it much easier to then ‘match’ an undated letter to the letter that it is answering,” she said. “This factor of having both (actually, all three and sometimes four) sides of the correspondence is what makes this collection unique.

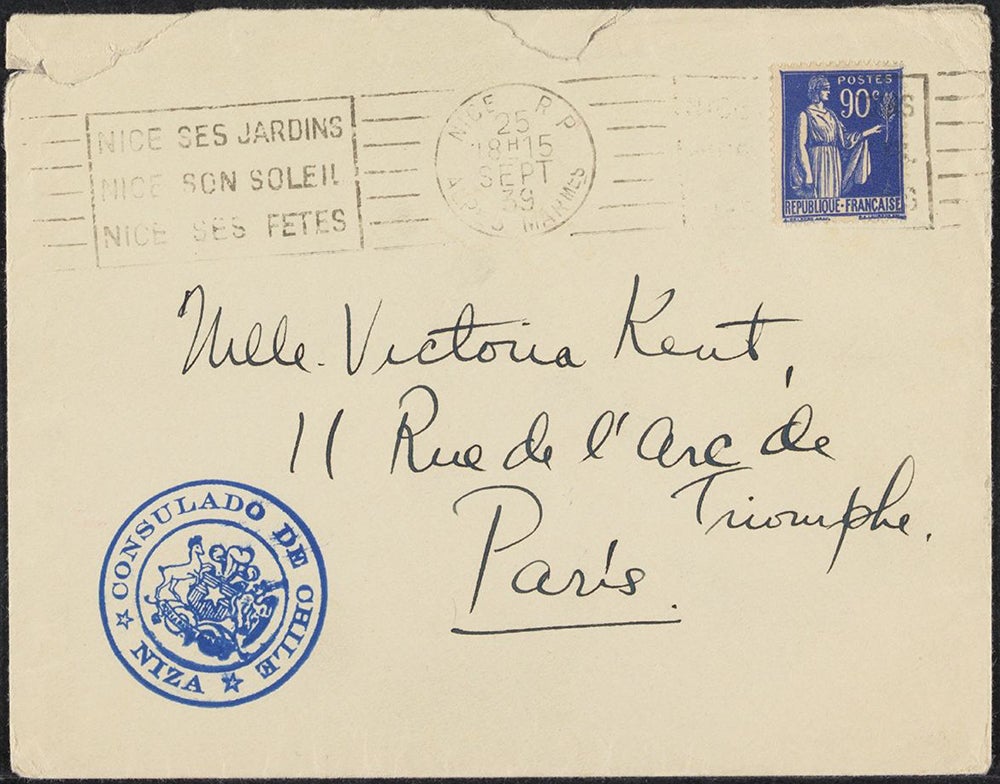

“Most collections of Mistral letters just show one side because the other person destroyed (or lost) the letters. But in this case, where the three women really very clearly valued their friendship, they kept almost all of the letters, despite multiple moves and, in Kent’s case, living in hiding in Paris throughout WWII.”

Photo courtesy Houghton Library, Harvard University.

During this time, the professors held a conference at ASU, funded by the Institute for Humanities Research and attended by internationally renowned scholars, to bring attention to their efforts. It was a huge success.

“The interesting thing about the conference was that because so many people left Spain for exile in Mexico (during the Spanish Civil War), there's a strong connection between the Spanish Republic and Mexico,” Horan said. “And there were a number of people in the audience who remembered growing up with these immigrants from Spain. So it was really quite moving.”

More is revealed

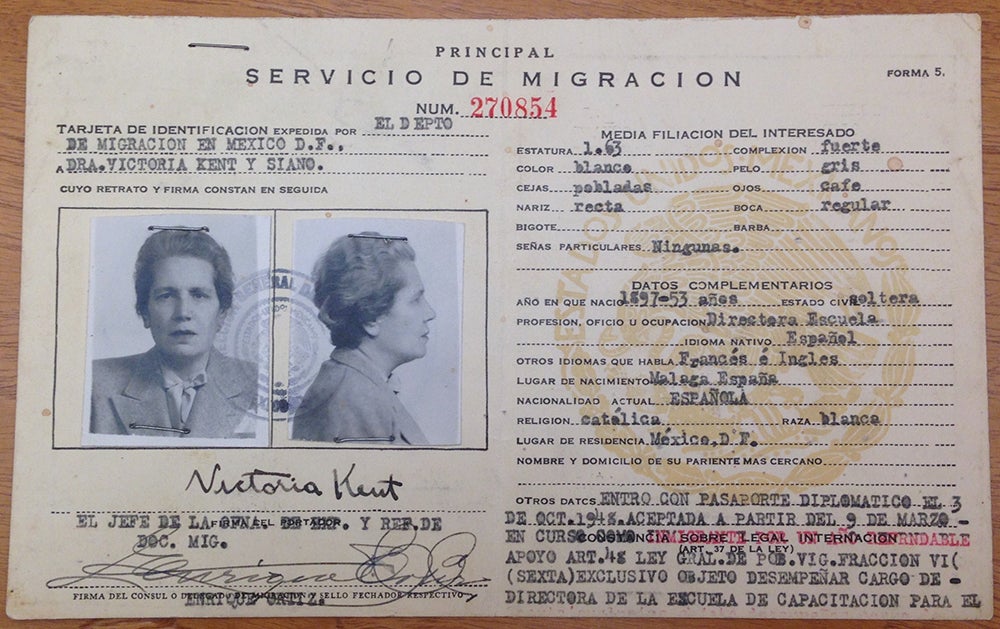

As they labored, the professors found themselves engrossed in the exploits of the women’s lives: Kent spent time in Paris caring for refugee children and living under a false identity during Nazi occupation, later recounted in her novel, “Four Years in Paris." Ocampo ran the successful magazine and publishing house, “Sur,” which showcased the likes of Pablo Neruda, Jorge Luis Borges and Frederico Garcia Lorca (“Sur” also published Kent’s aforementioned novel). Mistral had a relationship with Doris Dana, who like Kent’s partner Crane, also came from an aristocratic New York family and was also several years her junior (in the introduction to “Preciadas,” Horan ponders the erotics of medicine, noting that both Kent’s and Mistral’s much younger lovers also served as their caretakers). Mistral and Ocampo both endured quiet health struggles: The former suffered from complications due to diabetes, including partial blindness and kidney problems, while the latter lived with cancer for years. Mistral and Kent spent time in exile in Mexico.

Victoria Kent's migration card.

Sometimes the professors paused in their work simply to appreciate the women’s use of language.

“Mistral’s use of Spanish has always struck me as being extraordinary,” Horan said of the Nobel laureate. “She does things with the language you're not supposed to be able to do. It never ceases to amaze and delight me.”

Ocampo was trilingual, having grown up with English- and French-speaking governesses.

“And then Kent's Spanish is really interesting to me because her letters are so very different from her public self,” Horan said. “Her public self is almost scary. She's a lawyer. But her letters are very affectionate.”

They also learned things they could not have expected. Case in point: It was well-known that Mistral and a friend had together raised a boy she always claimed was her nephew.

“And we know otherwise,” Tompkins said.

“His exact parentage is still not clear,” Horan said, “but what is clear is that the documents surrounding his parentage were likely altered.”

They believe it may have been Kent who was able to help in that area, perhaps using her political connections to alter the documents. It is important to Horan to note, however, that Kent did nothing illegal.

“She was one of the most highly respected legal minds in Spain,” Horan said. “A brilliant lawyer who had studied with the best. Her actions were legal: She went to Barcelona, met with the judge of the family court and he agreed to sign off on it, although he also wrote her a note stating that he couldn’t say if the actions would be acknowledged by another country, since there was no signature from the boy’s supposed father, who no one (aside from Mistral) ever claims to have met.”

In dangerous times

Mistral, Kent and Ocampo became friends at an extraordinary time, Horan says.

“Women have just gotten the vote. Women are entering politics. Kent was the first woman to be a lawyer in Spain. One of the first to be elected to the equivalent of the House of Representatives. So it's an incredibly important time.”

It was also a dangerous time for women with a penchant for bucking tradition. One possible title the professors considered for the collection was “En Tiempos Peligrosos” (“In Dangerous Times”). In addition to everything the women endured — from illness to imprisonment to exile — Ocampo’s house was nearly burned down. Fortunately, she was not there at the time.

“People tried to shut them up,” Horan said. “They didn't succeed.”

The professors attribute that in large part to the deep well of support they were able to draw on through their friendship, maintained all those years through letters, and so they eventually settled on the current title, “Preciadas Cartas,” which loosely translates to “Greatly Valued Letters,” – or, as Urioste-Azcorra puts it, “letters that I love too much.”

"These friendships between women of that time are really important for understanding how they supported one another in public and how they made it possible to live independent lives in private."

— ASU Professor of English Elizabeth Horan

Throughout the project, the professors often wrestled with whether what they were reading should be made public.

“That was a sentiment we all had during the process,” Urioste-Azcorra said. “Because sometimes I said to Cynthia, ‘This is not a public document.’ I would transcribe a letter and I would see something that is very personal. It seemed to me that I was reading something forbidden.”

They forged ahead, though, because ultimately, they felt there was more value in the contents of the letters coming to light than remaining unknown forever. Perhaps in particular, Kent’s and Mistral’s queerness, and the important contribution it makes to LGBTQ history.

“’Yo soy lesbiana (I am lesbian),’ it wasn’t something you even thought to say then,” Horan said.

Yet it was clear from their common friends and acquaintances, and the spaces they inhabited (which Horan calls “sites of queer sociability”), how they identified. The professors agree that regardless of sexual orientation, Mistral, Kent and Ocampo were all very much part of a world of liberated women living at a point in the 20th century that was marked by great experimentation, conflict and change.

“Because of that, these friendships between women of that time are really important for understanding how they supported one another in public and how they made it possible to live independent lives in private,” Horan said.

Honoring a legacy

Kent and Ocampo continued to correspond after Mistral’s death in 1957.

“When they reflect on the last time they saw Mistral, it's very touching,” Tompkins said. During that last meeting, the only known photograph of the three of them together was taken. Ocampo is on the left, dressed to the nines with a fabulous hat and a pair of white-framed sunglasses. Mistral, gaunt and near death but still smiling, is in the middle. And Kent, seated on the right, appears resignedly content, donning a sensible jacket with a pocket square.

A little more than 20 years later, Ocampo died in 1979, and the letters stop.

“They were hiding for a very long time,” Urioste-Azcorra said, “and now it's time to recover their legacy.”

On a brief stop in Phoenix during her sabbatical, Horan is able to meet up with her friends Urioste-Azcorra and Tompkins at ASU to have their group portrait taken, because just like the other trio, they recently realized they don’t have one of all three of them either. In between shots, they chatter rapidly in Spanish, as if they’ve much to catch up on, while behind them, on a book shelf, sits the photo of Ocampo, Mistral and Kent.

Top photo courtesy Houghton Library, Harvard University

More Law, journalism and politics

Can elections results be counted quickly yet reliably?

Election results that are released as quickly as the public demands but are reliable enough to earn wide acceptance may not always be possible.At least that's what a bipartisan panel of elections…

Spring break trip to Hawaiʻi provides insight into Indigenous law

A group of Arizona State University law students spent a week in Hawaiʻi for spring break. And while they did take in some of the sites, sounds and tastes of the tropical destination, the trip…

LA journalists and officials gather to connect and salute fire coverage

Recognition of Los Angeles-area media coverage of the region’s January wildfires was the primary message as hundreds gathered at ASU California Center Broadway for an annual convening of journalists…