Many of the country’s top experts in technology and business met at Arizona State University last week to address the urgent issue of enhancing the United States’ competitiveness.

The group, which included CEOs, university presidents and accomplished researchers, was meeting for the first time to launch the National Commission on Innovation and Competitiveness Frontiers, part of the National Council on Competitiveness.

The daylong conference Thursday on the Tempe campus was the first step in a brainstorming process to tackle problems that have allowed the rest of the world to catch up with, and in some cases surpass, the structural competitive advantage of the U.S. Among the critical issues discussed were the decline of manufacturing in the United States, climate change and the rise of China on the global stage.

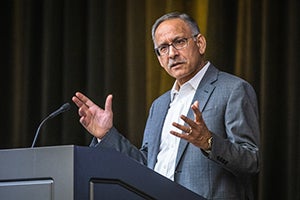

The commission members must come up with applied solutions, said Mehmood Khan, chairman of the commission and the CEO of Life Biosciences Inc.

“We’re not here to do hypothetical thinking around the distant future of a policy that might change things,” he said.

Khan said that the U.S. rose to dominance for two reasons: embracing immigrants and sharing its innovations.

“Federal investment and research into agriculture was responsible for the single biggest innovation in terms of lives saved. The dwarf wheat program saved a billion lives from famine and not one of them was American.”

Mehmood Khan, CEO of Life Biosciences and co-chairman of the National Commission on Competitiveness, speaks at the National Commission on Innovation and Competitiveness Frontiers’ Launch Conference at ASU. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

But American dominance is waning, Khan said.

One reason is demographics: A shrinking pool of young people is expected to support a huge generation of old people.

“Our entire infrastructure assumes a large, youthful base to support an older base. However, that system is not viable financially, operationally and most important from a manpower point of view,” he said.

ASU President Michael Crow is university vice-chair of the Council on Competitiveness. In his opening address to the group, he cited ASU as an example of an institution that improved by embracing systemic change.

“We decided that most universities were archaic, bureaucratic structures incapable of serving the United States to the level they needed to serve,” he said.

“More than half the people who go to college in the United States never graduate. Half the money that’s been spent on Pell grants has produced nothing.”

Video by Ken Fagan/ASU Now

After Crow became president in 2002, ASU eliminated 80 academic units, restructured 30 transdisciplinary entities and embraced hundreds of technology partnerships. The four-year graduation rate doubled.

Crow described how the engineering school was reinvented.

“We had a terrible weed-out culture we could not get rid of,” he said. “It was, ‘If you don’t have an A in calculus, too bad for you.’ You could be the greatest dreamer of something that could solve some huge problem but your calculus score was too low.”

So 11 engineering departments were eliminated and five “grand challenge” schools were created, along with the Polytechnic School.

“Ten years later we didn’t have 6,000 engineering students on campus with a 68% freshman retention rate, we had 17,000 engineering students on campus with a 90% freshman retention rate, from a broader spectrum of families. We’ve added thousands of women and thousands of minority students,” he said.

The transformation at ASU is important because it’s a microcosm of what the country needs, Crow said.

“What we need is more innovation, more innovators, more perspectives, more solutions, more energy,” he said, as well as an attitude that extends beyond wishing for more money from the government.

“This is our opportunity to do a reset.”

During the conference, the members divided into working groups and came up with several key issues for further work. Among them was concern about the rise of China. Long a hub of cheap manufacturing, the country is heavily investing in research and development of its technology industry.

Jennifer Curtis, dean of the College of Engineering at the University of California, Davis, said she’s seen a change in the students who are getting PhDs.

“I would say the U.S. is still preeminent in attracting international students to come here, but the big change was that, early in my career, those students would stay in the U.S., but now they are going back for great research and development positions. It will have a huge impact,” she said.

Some members worried about the technology supply chain.

“What China is doing is claiming a lot of territory in that area — not just manufacturing but materials. They’ve cornered the rare earth market,” said Edlyn Levine, lead physicist of the Emerging Technologies Group at the MITRE Corp. and a research associate in the Department of Physics at Harvard University.

She said that the American system isn’t always efficient for innovation.

“When you talk about prototyping or commercializing, if I have something I want to sell to you that I built, what is the barrier of entry in terms of the tax structure, environmental regulations, privacy regulations?” she said.

“Our government is never going to be China, but we should look at what’s hampering us.”

Education and training was another area of concern.

“The innovation engine needs fuel and the fuel is talent and it’s evaporating at the high schools. They don’t understand why it’s important to study calculus and math,” said Andre Doumitt, director of innovation development at the Aerospace Corp., who created an internship for high-school students at his company.

“You can tailor programs and link them to the opportunities that math and science bring because in the aerospace industry, we’re losing these kids to Google and Facebook.”

Deborah Wince-Smith, president and CEO of the Council on Competitiveness, said the new commission draws from all sectors of American business and is a “call to action” to transform the country’s innovation’s capacity.

“We have big challenges around our economic growth numbers,” she said. “Unless we return our productivity levels to historic standards of up to 1.5% to 2% or more per year, we will see, over time, a decline in our standard of living,” she said.

The experts on the National Commission on Innovation and Competitiveness Frontiers are expected to not only contribute their expertise, but also to leverage their powerful networks, Crow said.

“We should just get stuff going,” he said. “Figure out if there’s some way to get something going now — form a network or an alliance, or a new kind of business development methodology, or think about educational progress in a new way.

“We have to find a way to make innovation and competitiveness more egalitarian across the entirety of our society.”

Top image: Edlyn Levine, lead physicist of the Emerging Technologies Group at the MITRE Corp. and a research associate in the Department of Physics at Harvard University, speaks at the National Commission on Innovation and Competitiveness Frontiers Launch Conference at ASU last week. Photo by Charlie Leight/ASU Now

More Science and technology

ASU researchers engineer product that minimizes pavement damage in extreme weather

Arizona State University researchers have developed a product that prevents asphalt from softening in extreme heat and becoming brittle in freezing cold. The product reduces pavement cracks,…

New study finds the American dream is dying in big cities

Cities have long been celebrated as places of economic growth and social mobility, but new research suggests that their role in fostering opportunity has changed dramatically…

Ancient sea creatures offer fresh insights into cancer

Sponges are among the oldest animals on Earth, dating back at least 600 million years. Comprising thousands of species, some with lifespans of up to 10,000 years, they are a biological enigma.…