New exhibit shares rich history of African American communities in Arizona

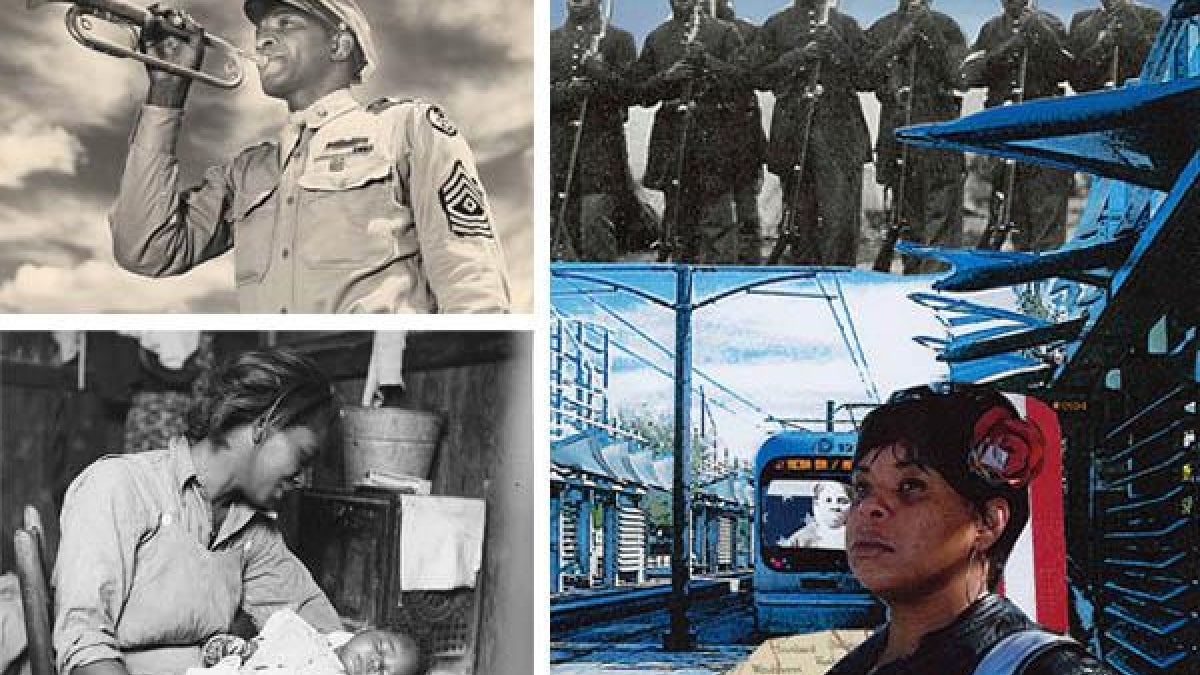

Photos and artwork courtesy of Rodney Grimes, C.A. Hammons, Dorthea Lange, National Archives and Records Administration.

Between 1910 and 1970, the African American population of Arizona grew from 2,000 to over 54,000, according to a new exhibit on display at Arizona State University’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change Innovation Gallery.

This growth was part of the Great Migration, during which more than 6 million African Americans moved from the rural American South to the cities of the North, Midwest and West.

Yet cultural, economic and political systems of that time often obscured the stories and accomplishments of those who migrated here from popular narratives about who Arizonans were and the lives they led.

Titled “The Great Migration: Indiscernables in Arizona,” the exhibit aims to help dismantle that marginalization through community partnerships, artistic expressions and social scientific research. It brought together a dozen Valley students to connect with elders in the community for face-to-face conversations where they used anthropological methodologies to collect oral histories and curate personal artifacts.

Those individual experiences were then woven together to create a more complete accounting of the migration and life afterward: of survival in spite of oppression and of the establishment of rich and enduring communities in the Valley — a legacy continues.

The exhibit’s organizers — Meskerem Glegziabher, clinical assistant professor and director for inclusion and community engagement at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change and C. A. Hammons, artist and founder of Emancipation Arts, a community arts organization which aims to honor enslaved ancestors through arts practices and public historical education — shared with ASU Now an insider perspective on the story behind its creation.

Question: What is Emancipation Arts? How and when did it start?

C. A. Hammons: I am a black artist who grew up in the downtown area of segregated Phoenix. I am also a writer, poet, activist, educator and prevention specialist. My special call is as a community builder and I have been fortunate enough to work in collaboration with numerous artists, organizations and individuals while being mindful of honoring my ancestors.

Emancipation Arts is a community organization that started in 2003 as a response to the lack of inclusiveness in public arts and a desire to participate locally.

Our mission is to raise the profile of black artists in Arizona and honor our African and enslaved ancestors through measurably influencing, constructively impacting and fortifying underserved, at-risk or neglected populations, with particular focus on African American, African and Caribbean immigrant and African refugee communities in Maricopa County, through arts and egalitarian collaborations. Our motto is “I promise you will learn what schools will not teach.”

I have also organized many exhibitions, community engagements, concert events and activities over the years but the medium and method of each depend on what I am trying to say. We just opened another exhibit called “The Spillover Effect,” at Modified Arts in downtown Phoenix, and we also have the Emancipation Marathon, a literary marathon that will be 24 years old this June.

C. A. Hammons (left) and Meskerem Glegziabher (right)

Q: How did the idea for the Great Migration collaboration begin to take shape?

Meskerem Glegziabher: We met two years ago at a monthly storytelling event called Vinyl Voices, where community members share stories and songs on vinyl to a live audience. The theme for that particular month was black migration to Arizona and Emancipation Arts hosted it.

We originally collaborated around another initiative called the Citywide Black Student Union because I was interested in bringing in students of color (especially black and Latinx) to ASU’s Open Door event to talk to them about potential careers in anthropology and global health.

CH: I have been writing a manuscript about the Great Migration and being an indiscernible in Arizona for a number of years and gradually shared some of it with Meskerem. Her curiosity and training as an anthropologist made it a fit because she could recognize the veracity of my assertions.

Q: Why was ASU and the SHESC Innovation Gallery a good temporary home for the exhibit?

MG: It was clear to me that my training in ethnographic research was something I could contribute as we looked to pair high school students with seniors for oral history interviews.

I was also having discussions at the time with our school’s director, Kaye Reed, about ways that the school could be more engaged with local communities and I was convinced the institutional support that we could provide — in terms of exhibit venue, production, etc. — could help bring to life this important project.

Q: How did your work and research at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change inform or overlap with the exhibit?

MG: In my role, I apply my qualitative research training in sociocultural anthropology and intersectional feminist thought to build sustainable relationships with local communities and community-based organizations, particularly those historically marginalized and underrepresented.

My research looks at how intersections of identity, such as race, class, gender and ability, result in particular types of marginalization and how these have very tangible and even physical impacts. I also study how mainstream narratives perpetuate marginalization and structural inequities and ways that, at a micro-scale, we can disrupt, mitigate or at least expose inequities.

This informs and overlaps with the historic experiences of African American Arizonans, who have been excluded from mainstream narratives of the state's history, but are pushing back against marginalization and erasure.

Q: What did the nature of each of your contributions look like?

CH: Essentially, the foundation grew from a quest to “honor my ancestors” as recommended by a Yoruba priest. Of necessity, the research, writing and paintings grew from my own family history and local experiences in recognition of the fact that as, a black Arizonan, I have been excluded from the narrative of the state’s history.

Workspace, funding and access have frequently been barriers to this work and other projects, so I have had to use my own funds and maintain a level of tenacity.

MG: I provided a workshop to give a background and train the students in how to conduct oral history interviews, did archival research to provide a larger context about the history of black migration and residence in Arizona, analyzed the interviews for striking quotes and condensed the archival research into the text for the exhibit panels.

The biggest challenge I faced was finding primary sources that provided information on the lives of average African Americans in Arizona in the early 20th century. The limited archival resources available tended to focus on either a handful of prominent families or institutions. So having firsthand accounts from elders in the community provided a unique opportunity to fill in some of those gaps.

Q: How many people were ultimately involved in and contributed to the project?

MG: Roughly 20 students and seniors contributed to the oral history and visual content. Two teachers at South Mountain High School, which has historically had a large African American student body, Fernando Sanchez and Bryan Willingham, presented the project to their students and recruited participants. The participating seniors were recruited from the extensive local networks Emancipation Art has.

CH: Many other people have supported this “obsession” as well. Asian Pacific Community in Action allowed us to use their conference room, filmmaker Bruce Nelson helped us prep students for their conversations by showing the film “Northtown” about segregated Mesa, and Donald R. Guillory — an instructor in ASU’s College of Integrative Sciences and Arts — donated signed copies of his book “The Token Black Guide” to students. These are just some of the ways community have helped.

MG: With all these individuals plus our core team, I would estimate around 35 total people were involved. We worked on it consistently for about one-and-a-half years, so actual research and production hours would be around 1,500 to 2,000.

C. A. Hammons with exhibit contributor and Arizona’s “King of the Blues” Big Pete Pearson.

Q: Is there any one piece that has special significance, symbolism or stands out to you the most?

CH: Probably the photo of my siblings and I as small children. One of my sisters passed away, but it makes me feel that she is with the ancestors smiling about the fact that blacks in Arizona will be acknowledged throughout the state and black children in classrooms throughout can hold their heads up.

MG: I think the different items featured have their own significance, but I think perhaps the most striking to me is the federal government's Home Owners' Loan Corporation "redlining" map of Phoenix from 1940. The area descriptions by local real estate professionals are so explicitly racist and classist that it provides a clear pushback against common narratives that Arizona provided a safe haven and fresh start for those fleeing the Jim Crow South.

Q: What do you hope people think about, feel and take away with them after viewing the exhibit?

CH: People will begin to scrutinize local history presentations that profess to present Arizona history yet acknowledge that blacks are excluded, and join us in rectifying those exclusions and bringing some integrity to historical presentations.

MG: I would like them to think about their own migration stories, how they or their families came to live in Arizona, and to walk away with the knowledge that the Valley has a rich and robust African American history, even if the population size is small. I would also like people, particularly African Americans, to feel proud in the knowledge that despite the marginalization and hurdles they have and continue to experience, they have also managed to build a resilient and thriving community here.

Q: What future programming will be in the Innovation Gallery after this exhibit?

MG: (School of Human Evolution and Social Change) exhibit developer Marco Albarran is working on a project for next semester with postdoctoral research associate Katherine Dungan called "Revealing Artifacts."

The goal for future Innovation Gallery exhibits is to design them all as traveling exhibits so that they can reach a larger audience beyond their tenure here. “The Great Migration: Indiscernables in Arizona,” will serve as a model for that. After December, Emancipations Arts will move it to the Rosson House at Heritage Square, then other locations in Douglas, Buckeye and Chandler.

This exhibit is free to the public and is on display weekdays 8 a.m.-5 p.m. at the School of Human Evolution and Social Change Innovation Gallery.

Remodeled in 2018, the Innovation Gallery hosts different exhibits on the nature of the school’s work and myriad aspects of the human story and experience.

More Arts, humanities and education

March Mammal Madness hypes science, storytelling in the classroom and beyond

In classrooms throughout the country, the buzz around March Mammal Madness starts long before the tournament begins. For…

Different ways of thinking, different ways of thriving: How ASU is supporting students with autism

According to the CDC, over 5.4 million adults in the U.S. are living with autism spectrum disorder, a condition that affects…

Forever sewn in history

The historical significance of Black influence on fashion spans centuries. From the prints and styles of Africa to various…