ASU working to save Hawaiian coral reefs during onset of new ocean heat wave

Editor's note: Be sure to check back on ASU Now for this developing story, and the website Hawaiicoral.org as we provide further updates. Or follow us on social media: @hawaiicoral_org — @greg_asner — @ASU_GDCS @asunews — #coralbleaching2019

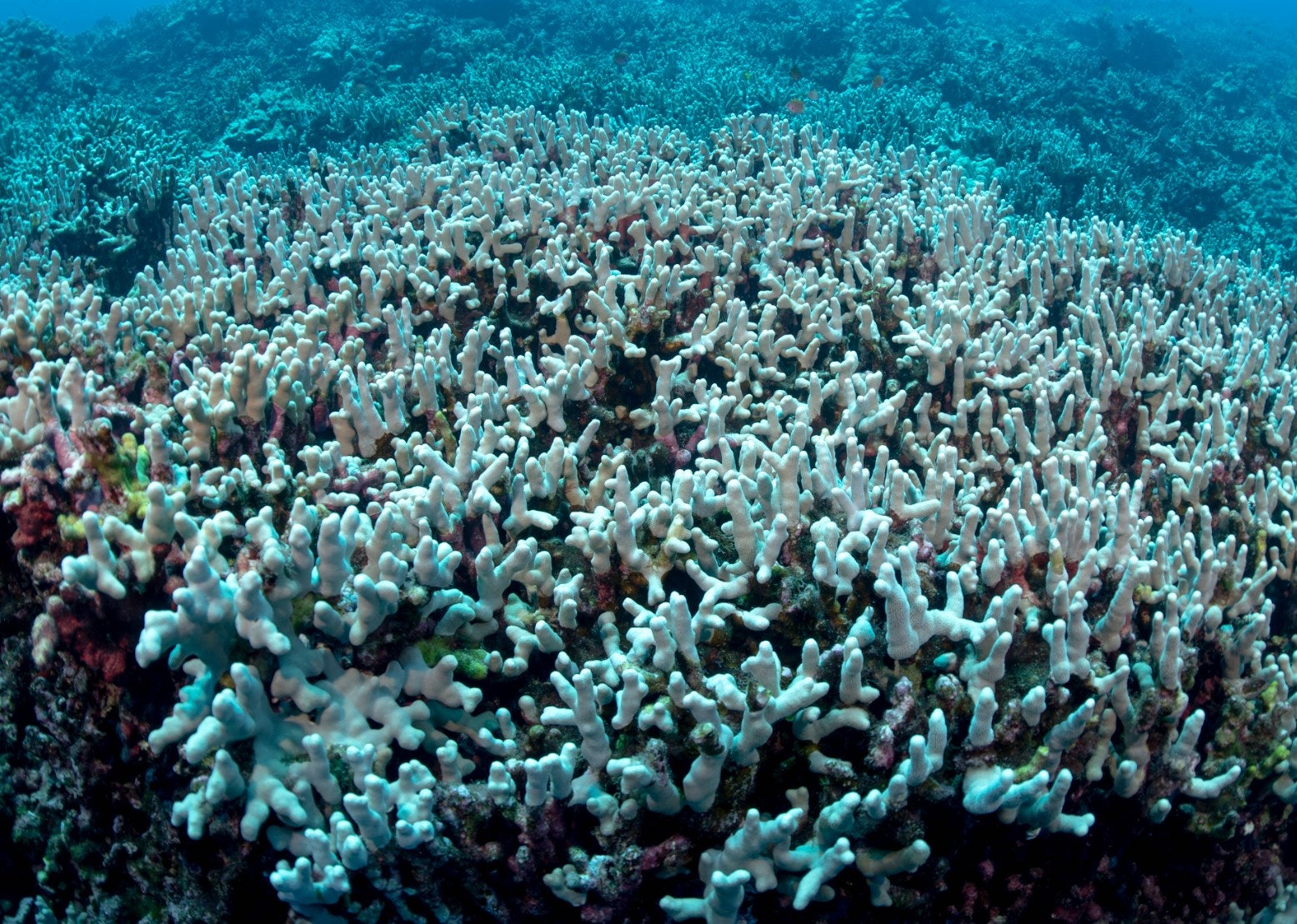

ASU ecologist Greg Asner recently captured this photo of bleaching corals while conducting fieldwork in Hawaii.

UPDATE: Jan. 31, 2020

Following the 2019 Pacific Ocean heatwave that produced widespread coral reef bleaching, scientists from the Arizona State University Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science (GDCS), Department of Land and Natural Resources’s Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR), and National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) teamed together to assess coral health across Hawaii.

Now that ocean temperatures have stabilized, their top question has shifted to recovery efforts. What survived the heat? To answer that question, ASU’s unique “superplane,” the Global Airborne Observatory (GAO), has taken to the skies once again.

The Global Airborne Observatory captured by its wing cams as it flies of Hawaii's reefs.

The aircraft’s advanced mapping technology is creating high-resolution maps of reefs along Hawaii’s coastlines. According to GDCS director and GAO founder Greg Asner, “We’re looking for a net change in live coral cover on reefs. Our airborne observatory has unique capabilities that allow us to see through seawater to a depth of 70 feet. What we want to see is where there’s live coral on the seafloor, where there’s dead coral, where there’s algae, the depth of the water, and 3D habitat for fish.”

Although the GAO was grounded for the first few weeks of 2020 due to bad weather, the team lost little time since conditions improved, already mapping an estimated 30% of Hawaii’s reefs to date.

The GAO’s surveys provide complementary data to what is collected from both intensive dive surveys and satellite monitoring that are combined to provide a complete picture of coral health. In November 2019, Asner’s team announced that, for the first time ever, coral reef bleaching was being tracked in real-time using this three-pronged approach. The monitoring system was a beta version they had been developing for the Allen Coral Atlas to eventually monitor coral reefs worldwide.

This map of West Maui's live coral (yellow) taken in January 2019 is now informing Greg Asner and his team's flightpath for 2020.

Asner said, “There is no amount of diving that is going to give us enough coverage to understand what’s going on with Hawaii’s coral reefs. The area is too large and complex to get to it by diving alone…even with the thousands of hours of diving each year. Our platform gives us full coverage and the context for additional fieldwork that focuses on one of the three major issues impacting corals reefs.”

In the aftermath of the coral die-off, what surprised Asner and his team the most was finding that bleaching patterns were not uniform for all coral species. Some coral species were resilient to the increase in sea temperatures while others were much more vulnerable. This observation has implications for the future of coral reef ecosystems as ocean warming events like the one in 2019 become more frequent due to climate change. In fact, Hawaii has experienced serious bleaching in three of the past five years. Asner added, “Bleaching stresses reefs—and NOAA predicts we’ll have these marine heatwaves every year or two by 2030.”

But ocean warming isn’t the only threat to coral reefs — land-based pollution, sedimentation, and overfishing all play an important role in damaging coastal ecosystems. To address these coastal factors during the 2019 ocean heatwave, Asner’s team created Hawaiicoral.org, a massively successful citizen science and public outreach effort that utilized hundreds of coral bleaching reports made by Hawaii’s citizens to direct both fieldwork and satellite observations.

Looking back on that project, Asner said, “Citizen science turned out to be transformative in our effort — not only as scientists but also in terms of getting people on board with the reality that coral reef ecosystems are changing and that we all have to do our best to support a better future through our individual contributions. Citizen scientists were our best advocates; they helped to spread the word across their communities about where coral bleaching was happening locally, which helped to get people off the reefs and be more aware of reducing any additional stress to reef ecosystems, and they also played a critical role in helping to confirm our satellite observations and to direct our fieldwork. Going forward, I can’t imagine initiating a project of this scale that doesn’t have a citizen science component built into it.”

Global Airborne Observatory mapping tech Joseph Heckler teaches an Asner Lab graduate student Megs Seeley about the aircraft's advanced mapping technology while flying over Hawaii.

With support from the Lenfest Ocean Program, Asner and his team plan to continue mapping Hawaii in 2020 while working with Hawaii’s government to develop a restoration and conservation plan for coral reef ecosystems across the state.

The data and insights gathered from this work will contribute to Governor David Ige’s Marine 30X30 Initiative, a plan to expand Hawaii’s network of marine managed areas to at least 30% of Hawaii’s reefs by 2030. DAR Administrator Brian Neilson commented, “For many years we’ve conducted regular diving surveys and assessments to create data that helps guide management decisions. Obviously mapping this way is time-intensive and we would never be able to survey all of our near-shore reefs. The Global Airborne Observatory will produce a full and complete map of every reef and do it in about 30 days of flying. This information is critical for managing our near-shore reefs and developing strategies to help our corals survive the impacts of climate change.”

In concert to mapping Hawaii, Asner is continuing the team’s field operations focusing on untangling the drivers behind coral species resilience. Additionally, he and his team will extend the three-pronged methodology used to monitor coral reef bleaching in Hawaii to French Polynesia, which recently experienced a coral reef bleaching event. This research is also for the Allen Coral Atlas, which is funded by Vulcan Inc.

UPDATE: Nov. 7, 2019

Major takeaways:

- The satellite-based monitoring component of Hawaiicoral.org’s coral reef bleaching tracker has been successfully deployed; this is the first time coral bleaching has ever been tracked by satellites in real time.

- The tracker has revealed “hot spots” of bleaching across the Hawaiian Islands between zero to 10 meters depth.

- Hawaii has just passed peak ocean temperatures, which means that some corals will likely begin to recover.

In a meeting of reef bleaching specialists held at the Hawaiʻi Institute of Marine Biology on Nov. 6 on Oahu, Greg Asner, director of Arizona State University’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science (GDCS), announced that the satellite-based monitoring component of Hawaiicoral.org’s coral reef bleaching tracker has been successfully deployed. This is the first time coral bleaching has ever been tracked by satellites in real-time and represents a significant scientific milestone that will improve coral reef restoration and conservation strategies.

The new monitoring system is a beta version of the one Asner's lab is developing for the Allen Coral Atlas, a project working to create the first reef bleaching monitoring system for the world’s coral reefs.

“We combined our field, airborne and satellite-based science to generate a monitoring approach that clearly shows the progression of the 2019 coral bleaching event across the main Hawaiian Islands,” noted Asner as he demonstrated the system at the reef meeting held on Coconut Island, Oahu.

Video from Hawaiicoral.org shows the first-ever time series of coral reef bleaching during the 2019 ocean heatwave.

The marine heat wave arrived to the Hawaiian Islands in August, and NOAA has reported that it was the second-largest event in the region in the past 40 years. By the end of September, sea surface temperatures had elevated by 3.5 degrees Farhenheit. As expected, coral reefs began to show signs of bleaching, but the geographic pattern of bleaching was highly variable.

“There are hot spots of coral bleaching that were undetected even among dozens of organizations, including ours, using snorkeling and diving methods alone. The pattern of bleaching is always geographically complex, and this was no exception. Now, with our new approach, we can see how the event unfolded from the perspective of the actual corals that were affected,’’ said Asner at the podium.

During the bleaching event, Asner and his team created Hawaiicoral.org in partnership with Hawaii’s Division of Aquatic Resources, NOAA, and the San Francisco-based satellite company Planet as a response to a severe Pacific Ocean warming event (see the New York Times' "The Return of the 'Blob'" feature), predicted to arrive in the late summer 2019.

The initiative received funding from Vulcan Inc. as part of Asner’s work with the Allen Coral Atlas, a project that aims to map and monitor coral reefs worldwide. Next, Asner put Hawaiicoral.org in motion, launching a massive citizen science effort that to date has compiled more than 100,000 social media interactions and over 500 individual and community-wide reports of local bleaching to calibrate Planet’s satellites and hone Asner’s multi-pronged fieldwork strategy.

“The citizen reports were critical and continue to be critical in pointing us professional scientists in the right direction for our fieldwork measurements,” said Asner. “However, citizen reports naturally biased regions in Hawaii where people have access to the ocean, and so the maps informed by those reports versus satellite data give us two different perspectives on the same problem.”

Recent photo by Greg Asner of bleaching corals in Hawaii.

The satellite maps are unique for utilizing algorithms trained to detect changes in the seafloor’s color and tone captured within Planet’s satellite data as they continuously pass over reefs. With these new maps, Asner and his team now have the information they need to target fieldwork in regions experiencing the worst bleaching. The team hopes to find and identify heat-resistant coral species in these regions for potential use in future coral reef restoration efforts. Asner, a professional deep diver, and several of his teammates are also investigating coral bleaching at depths well below the satellites’ range of 10 meters.

As for the heating event, they are hoping that the worst is now over. The latest sea surface temperatures have shown a decline over the past week, reported by NOAA at the Oahu meeting Nov. 6. Over the next few weeks, the scientists expect that some portion of the bleached corals may begin to recover, which the satellite maps will show as areas of darkening. This darkening, however, could be due to either coral recovery or algal cover — only fieldwork will be able to discern between the two.

“The new satellite monitoring system is a key contribution to the state of Hawaii’s expansion of its reef management strategy, which must face the reality of periodic marine heat waves associated with climatic change,” commented Brian Neilson, head of the state’s Division of Aquatic Resources. “Now that we see the geographic pattern of bleaching, we can better plan for protections and restoration of Hawaii’s unique coral reef ecosystems.”

— Written by Heather D'Angelo, communications director, Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science

—

ASU's Robin Martin and Patrick Gartrell are shown in the field measuring living and dying coral in preparation for the ocean heat wave in Hawaii.

UPDATE: Oct. 1, 2019

When oceans warm, how resilient are coral?

With increasingly warming waters becoming a global threat to coral reef health, efforts of the state of Hawaii have gained worldwide attention. And the community’s response to report bleaching and further stressors to the reefs has been integrated into the daily efforts of the Asner lab’s real-time research and monitoring.

“My team has created a novel way to understand the ecological impacts of coral bleaching events by integrating outreach and citizen science engagement with multi-scale field, airborne and satellite scientific measurements,” said Asner, director of ASU’s GDGC. “The approach allows us to scale up from individual corals to vast reef regions like the Hawaiian Islands, while simultaneously engaging and educating the public on ways to help mitigate the most egregious impacts of climate change on coral reefs.”

The Asner team makes long (1-5 km) transects along the seafloor of the Big Island’s Papa Bay.

The overall goal of Asner’s fieldwork during the warming event has been to untangle the complex three-way interactions between coral species, habitat and water depth governing coral reef ecosystems. Since the warming began in early September, scientists have observed that some coral species are better able to withstand higher sea temperatures while others quickly bleach. According to Asner, there is no clear pattern underlying this variation in response.

“We’ve long known that coral responses to marine heat waves vary at a range of scales, from individual corals within a species, to different species and communities of corals, and up to ecosystem- and regional-level differences. But the ecological pattern has never been mapped out and, therefore, never understood at any substantive geographic scale anywhere in the world”

One of the goals of his team’s research is to uncover if coral survival rates correlate to where they are located and also in terms of water depth. He also aims to discern if some coral species are better adapted to enduring longer durations of warming than others since isolated regions of the Pacific are expected to experience the same kinds of heat waves as happened during the 2015 warming event. The consequences for corals and other wildlife exposed to such long and slow periods of simmering remains a question that Asner hopes to answer.

Now, with his team hard at work performing daily and repeated measurements of ocean conditions, coral extent and coral health on the Big Island, Asner is beginning to unravel the puzzle.

First, based on the bleaching reports, an underwater vehicle he developed makes long (1-5 km) transects along the seafloor of the Big Island’s Papa Bay, taking high-resolution videos of corals while also collecting spectral and chemical information on corals, as well as depth and temperature of the water. While one of Asner’s teams focuses on the conditions at their main research sites in Papa, Honaunau and Kiholo bays on the Big Island, another team takes measurements along shorter transects at different locales across the Big Island, providing “spot checks” of the same ecological markers that could alert the team to impending bleaching conditions.

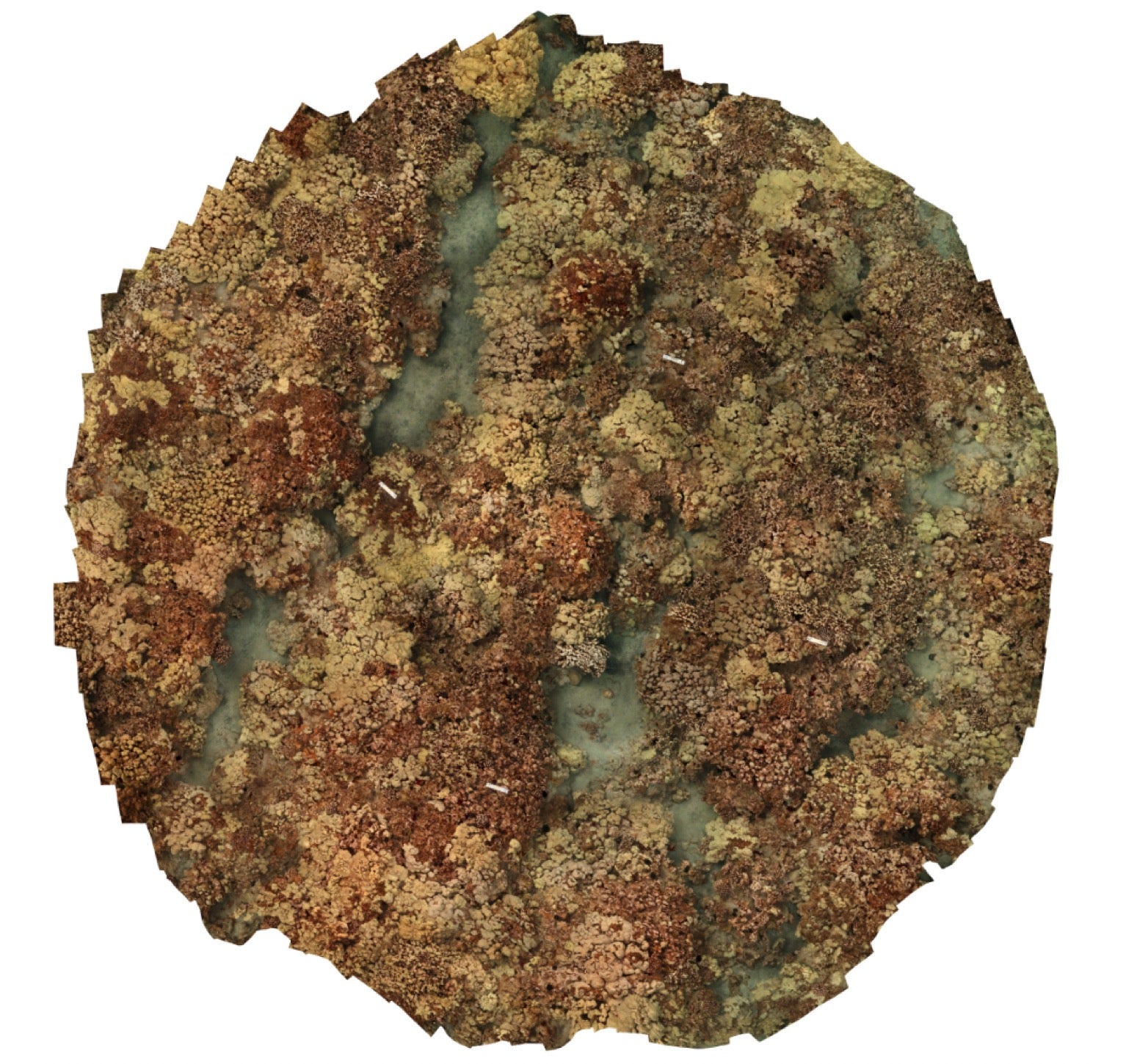

Using structure-from-motion analysis technology, Robin Martin's group stitches together thousands of photos of corals from different angles to reconstruct the reefs into a composite 3D image.

Next, the reefs are ready for their close-up. Robin Martin, an associate professor at the School of Geographical Sciences and Urban Planning, is leading an innovative 3D underwater photomapping endeavor.

First, Martin’s teams work across multiple bays across the Big Island, diving down to the seafloor to take thousands of photos. Next, they deploy structure-from-motion analysis technology, which puts together thousands of photos of corals from different angles to reconstruct the reefs into a composite 3D image.

For example, in just one circular 12-meter-diameter plot, up to 10 different species of coral may coexist, with each responding to warming ocean temperatures in a uniquely observable way. By documenting corals before, during and after bleaching, Martin and her team will have a record of coral resilience throughout the 2019 marine heat wave event.

Given how popular Hawaii is as a destination for tourists and water recreational activities, investigating the localized human-driven toll on reef ecosystems is also woven into Asner’s multi-pronged research strategy. Asner’s PhD student, Rachel Carlson, measures water quality, also known as turbidity, and its relation to coral bleaching. Areas of low-quality water become contaminated due to runoff from the land, usually from homes, hotels and golf courses. These areas of low-quality water may intensify coral bleaching at nearby sites; as high temperatures in the Pacific extend into the holiday season, there will be more opportunities for Asner’s team to study coral ecosystems along high-traffic coastlines.

Lastly, to round out the picture of how ocean warming affects Hawaii’s ocean ecosystems, Asner’s team is also conducting an intensive study of fish and invertebrates to measure the rich biodiversity that corals support. Using fish camera traps that take one photo every 10 minutes from dawn to dusk, the team is interested in how different species respond to bleaching conditions.

Using fish camera traps that take one photo every 10 minutes from dawn to dusk, the research team is interested in how different species respond to bleaching conditions.

Previous research has shown higher coral survival rates in areas with dense fish populations. Marine heat waves drive an overgrowth of algae, which ultimately causes coral bleaching and death. But fish can act like a coral fire and rescue team, springing into action to prune the algae overgrowth — and save the corals. By essentially spying on the fish populations using the camera traps, Asner’s team will be able to find out if the environmental changes to the local ecosystem caused by the heat wave will also make the protective fish abandon their coral habitats.

Their research also has implications for how Hawaii manages its fishing policies; Hawaii is under intense fishing pressure, and if high fish counts improve coral resilience, then policies to curb fishing during bleaching events might also make sense.

"In the end, our multi-scale approach, which goes from individual corals to satellite-based maps of reef change, is about educating the public and providing actionable pathways to improve coral reef management in what will be repeated marine heat waves driven by the climate crisis," said Asner. "Managing reefs, including their coral and fish populations, can no longer be done effectively without a new proactive management approach, which must be based on the multi-scale monitoring capability that we have pioneered."

— Written by Heather D'Angelo, communications director, Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science

UPDATE: Sept. 24, 2019

Ocean cauldron is creating widespread coral bleaching across Hawaii

In Hawaii, citizen scientists have sprung into action to help save the greatest source of ocean life diversity, its coral reefs during record-breaking high temperatures this summer.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicted in early August that there would be a widespread and severe bleaching event in the coming months after tracking a “blob” of warm water moving toward the Pacific, akin to one that triggered widespread bleaching in 2015.

Now, the blob has arrived.

This time, NOAA, the DLNR Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR), and the Arizona State University Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science (ASU-GDCS) have joined forces to collaborate on coral reef science, conservation and management in Hawaii.

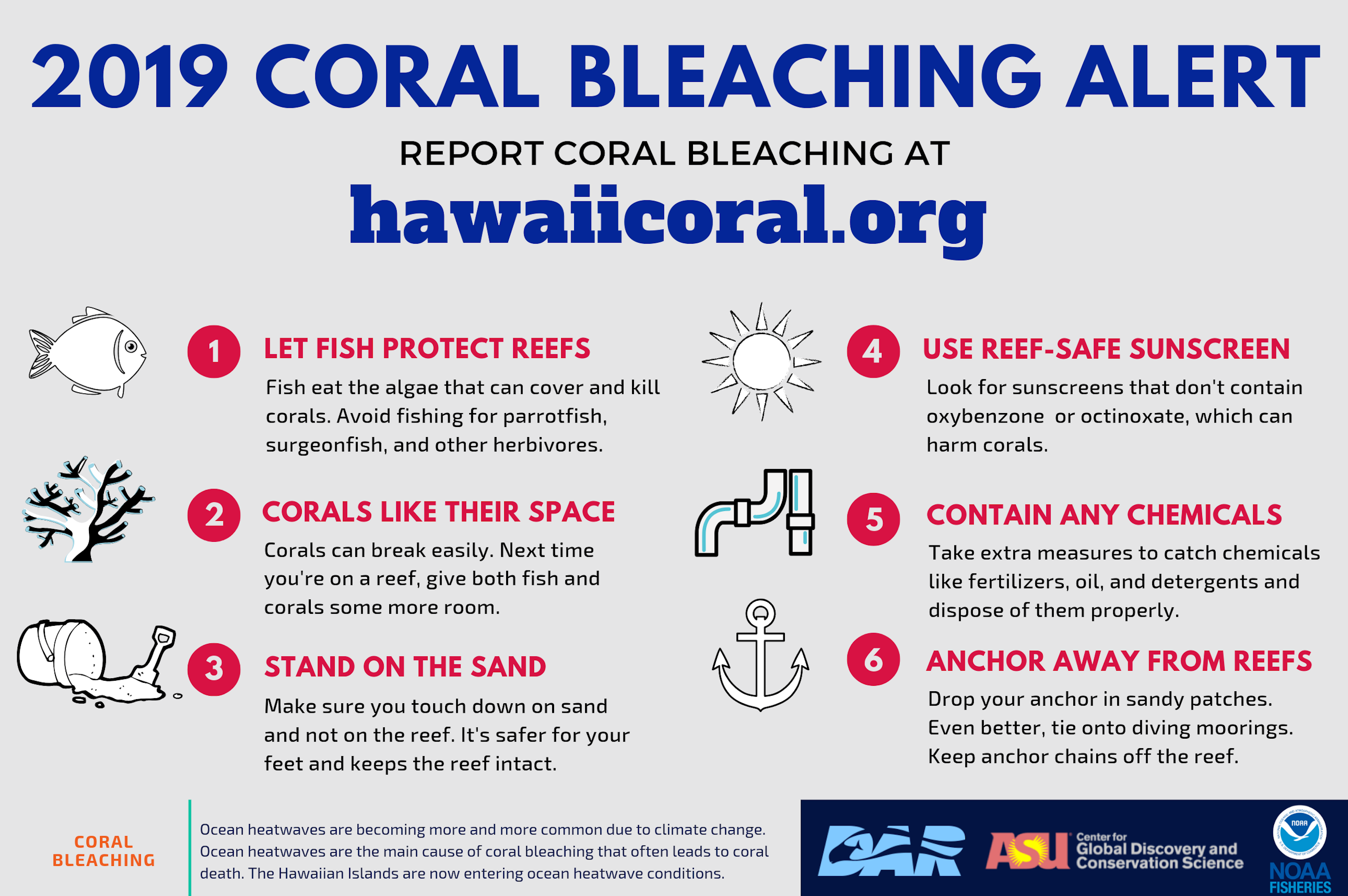

One of the outcomes of this partnership is the creation of a coral bleaching alert card, which depicts a list of six steps people can take to reduce any additional stress on corals during the current bleaching event.

ASU-GDCS research scientists recently hit the streets to distribute these cards to local dive and local tourist shops.

With a better-informed community, everyone is doing their part to help save the coral reefs.

The Governor’s Office issued another statement to raise awareness, and last week, a team from DAR conducted a rapid assessment of coral health at Molokini and along Maui’s south shore from Makena to Maalaea.

The National Coral Reef Monitoring Program surveyed the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument and found extensive bleaching. At Kure Atoll, the northernmost atoll in the archipelago, almost 100 percent of shallow-water corals (less than 15 feet deep) are bleached. Severe coral bleaching is predicted to extend across the Hawaiian Archipelago, and citizen science reports of bleaching have confirmed this widespread bleaching.

Russell Sparks, a DAR aquatic biologist reported, “Molokini is composed of high percentages of the coral species, Montipora capitata, and we found roughly 50% of this coral already bleached or paling heavily.” The DAR team found in waters off Makena, Wailea and Kihei the percentage of corals showing bleaching currently at less than 10%.

Warm ocean temperatures are expected to persist in the coming weeks, likely worsening the coral bleaching that has recently been observed across the islands.

ASU-GDCS has been focused on monitoring on Hawaii’s Big Island and has seen similar bleaching in the pristine waters of Papa Bay.

“We just finished installing 6 new fish camera traps in #Hawaii to monitor changes in fish communities during and after the bleaching event," said Asner, director of ASU-GDCS. "We're geared up and ready to finish pre-to-early coral bleaching measurements as the ocean heat wave intensifies. Using fish camera traps, underwater temp sensors and PLANET labs satelliate imagery, we're tackling coral reef research from above and from below."

Why are so many coming together to help save coral reefs?

For the sea, coral reefs are like the rainforests on land in their support of biodiversity (see https://blog.ted.com/nature-revealed-biodiversity-in-3d-greg-asner-at-tedglobal-2013).

According to Hawaii’s Division of Aquatic Resources (https://dlnr.hawaii.gov/dar/habitat/coral-reefs/), even though coral reefs cover just a tiny fraction of the ocean floor, they support almost one-third of the world’s marine fish species. On mid-September, with alarming news of up to 3 billion or almost one-third of the entire bird population of North America lost due to human activity, the fear is that the oceans are next.

Sometimes corals are able to recover from bleaching. However, they can die if stressors, such as warmer ocean temperatures, continue. Studies have shown that if local stressors are reduced before, during and after bleaching events, corals are more likely to recover. Local stressors include human impacts, such as unintentionally knocking over coral while snorkeling or diving, boat anchors hitting coral, unsustainable fishing practices and pollution from nearby watersheds.

The Hawai‘i’s Department of Land and Natural Resources will introduce an initiative in October aimed at tour operators to inform their guests about good reef practices. Numerous operators, like Fair Wind Big Island Ocean Guides on Hawai‘i Island, are already educating people on their boats. They ask them not to stand on, sit on or touch the reef and to use reef-safe sunscreen products.

Worldwide, about 400 million people depend on coral reefs for work, food and protection. Hawaii is no different. Yet every single reef could be gone or threatened by global heating and ocean heat waves, especially if they become an annual event.

UPDATE: Sept. 3, 2019

Citizen scientists give first reports of widespread coral bleaching events across Hawaiian Islands

On Aug. 23, after the Hawaii Gov. David Y. Ige’s office issued a plea for help dealing with a pending widespread and severe coral bleaching event during an ocean heat wave, early efforts have been focused on informing the community of how they can best help save the reefs.

Through word of mouth and social media efforts, the Hawaii state government, local tourism offices and dive and surf shops have been spreading the word to its citizen scientists of being the extra eyes on the reef to help state and federal managers monitor and best respond to the ongoing bleaching event.

“During the past eight days since the Governor’s Office announcement, there have been 62 reports of bleaching events coming from our citizen scientists,” said Greg Asner, who directs Arizona State University’s Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science.

This past week, Asner has been in a series of emergency meetings with state and federal officials to help mitigate the harmful effects of the looming coral reef crisis.

ASU helped launch a citizen science and satellite tracking effort for sharing information and reporting coral bleaching. Quickly, Asner’s team created Hawaiicoral.org, a partnership between the Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science (Twitter @ASU_GDCS), NOAA (@NOAA) and Hawaii's Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR), Planet (@planetlabs) and Allen Coral Atlas (@AllenCoralAtlas) to inform about coral reef bleaching in Hawaii and to galvanize action.

To help map incoming reports, the website offers an easy interactive tool for citizens to report the location and severity of bleaching events.

The map shows reports of moderate to severe bleaching already underway from out west on Kauai to the Big Island. Responding to these reports, GDCS scientists like Robin Martin and Patrick Gartrell have been measuring living and dying coral in preparation for the ocean heat wave (see: https://twitter.com/HawaiiCoral_Org/status/1168780178882990081?s=20).

The latest temperature update from NOAA offer little solace for relief for the coral reefs, as sea surface temperatures continue to rise toward the levels found during the worst mass bleaching event in 2015 (see: https://twitter.com/HawaiiCoral_Org/status/1168842078400499712?s=20).

For Hawaii’s communities, people are asked to be ready to get out to the reefs and help by reporting any bleaching Hawaiicoral.org. Please participate and spread the word. #coralbleaching2019 @asuresearch

On Twitter, please follow @hawaiicoral_org for updates on ASU's work with Hawaii's Division of Aquatic Resources & @NOAA monitoring coral reef health during the current ocean heat wave in #Hawaii.

UPDATE: Aug. 23, 2019

July ended with the hottest recorded average temperature since people have been making daily readings. With the warming, climate change is ensured. A huge chunk of Greenland has melted, Arctic seas have opened, and the diversity of life on Earth may be threatened.

Now, the effects are spreading across the Hawaiian Islands, with some of the most diverse and abundant life under peril due to a massive coral bleaching event underway.

According to NOAA scientist Jamison Gove, "Ocean temperatures are extremely warm right now across Hawaii, about 3°F warmer than what we typically experience in mid-August. If the ocean continues to warm even further as projected, we are likely to witness severe and widespread coral bleaching across the islands."

This event is coming a mere four years after the unprecedented bleaching events of 2014 and 2015. Just as the Hawaiian coral reefs were showing remarkable resiliency and making a recovery, they are faced with yet another event.

Coral bleaching is a change from normal coloration of browns, yellows and greens to a nearly white color. This change occurs when corals are stressed by environmental changes, especially temperature increases. Although corals can recover from moderate levels of heat, if it is prolonged, they will die.

But scientists say that reducing secondary stress on corals during these ocean heat waves can improve the chances of coral survival.

According to Division of Aquatic Resources (DAR) administrator Brian Neilson, “We know this bleaching event is coming, and it’s probably going to be worse than the one we experienced a couple of years ago, when West Hawaii experienced a 50% mortality rate and Maui experience 20-30% mortality rates on DAR fixed monitoring sites. We’re asking for everyone’s help in trying to be proactive and minimize any additional stress put on coral.”

As part of its sustainability commitment to help preserve life on Earth, Arizona State University is leading the effort to help Hawaiians save the reefs by providing real-time monitoring in support of DAR's efforts.

"The work that the team is doing here, in cooperation with DAR, is the first time on planet Earth that we are doing real-time monitoring of a bleaching event," said Greg Asner, who directs the new ASU Center for Global Discovery and Conservation Science.

Their suite of technology has extensively mapped the state of coral reef health before the warming event. Now, their heroic efforts will monitor the warming ocean’s impact on coral bleaching through space satellite imaging, 3D laser mapping from the air and sensors sunken on the ocean floor.

"The sea surface-temperature alert already went up, and this is the highest temperature ever recorded in Hawaii," Asner said. “But bleaching is not death, so there is still a chance to save the coral reefs.”

Asner mentions that what ultimately kills coral are algae, who thrive and multiply with the higher temperatures, gobbling up all the surrounding oxygen and snuffing out coral and ocean life.

DAR is working with the Hawaiian community on simple ways that they can specifically help:

- Avoid touching the reef while diving, snorkeling or swimming.

- Do not stand or rest on corals.

- Use sunscreens with no oxybenzone or octinoxate.

- Boaters should use mooring buoys, or anchor only in sand areas and keep anchor chains off the reef.

- Fishers should reduce or stop their take of herbivores, such as parrotfish, surgeonfish and sea urchins. Herbivores clear reefs of algae, which overgrow and kill corals during bleaching events.

- Taking extra precaution to prevent contaminants from getting to the ocean like dirt from neighboring earthwork, chemical pollution from fertilizers, and soaps and detergents getting to storm drains.

Together, through state agencies, ASU research and the community, they may help stem the tide on coral bleaching.

A bleached coral from the unprecedented bleaching events of 2014 and 2015. Just as the Hawaiian coral reefs were showing remarkable resiliency and making a recovery, they are faced with yet another event in 2019.

More Environment and sustainability

Rethinking Water West conference explores sustainable solutions

How do you secure a future with clean, affordable water for fast-growing populations in places that are contending with unending drought, rising heat and a lot of outdated water supply infrastructure…

Meet the young students who designed an ocean-cleaning robot

A classroom in the middle of the Sonoran Desert might be the last place you’d expect to find ocean research — but that’s exactly what’s happening at Harvest Preparatory Academy in Yuma, Arizona.…

From ASU to the Amazon: Student bridges communities with solar canoe project

While Elizabeth Swanson Andi’s peers were lining up to collect their diplomas at the fall 2018 graduation ceremony at Arizona State University, she was on a plane headed to the Amazon rainforest in…