As any grad student can tell you, science can involve horrible jobs: combing through poo, flensing carcasses, any number of “pipette monkey” tasks.

But there is a job so terrible and numbing, so doomed to end in cursing and tears and cramped hands and trembling fingers, that all else pales before it.

Identifying thousands of ants.

Andrew Burchill is earning a doctorate in collective animal behavior with Arizona State University's Social Insect Research Group. His career in myrmecology — the study of ants — lies ahead of him, but he may have already made his mark in what he calls “the niche science of mass animal christening” by co-creating a fool-proof system to label thousands of anything: schools of fish, flocks of birds, mounds of termites.

It may result in shrines to St. Burchill of Tempe in every myrmecology lab across the land. “It’s somewhat of a niche audience,” he admits.

This is a story of how engineering combined with biology to solve a problem.

Let Burchill describe what it’s like to paint tags on anesthetized ants on a tiny foam platform under a microscope, using a single human eyelash taped to a toothpick:

“I squint and my vision narrows until everything I can see is in a small circle surrounded by darkness. I’ve lost feeling in my left leg and a tremor shakes my already-cramping hand. For the last few hours the nervous energy in my body has screamed for release, but I desperately try to wrestle my attention back to the matter at hand.”

It gets worse. Ants are some of the cleanest creatures on earth. They spend hours every day grooming themselves. Burchill would return to the lab to find tiny paint chips in the ants’ trash heap.

Back up a bit. Why paint hundreds or thousands of ants? In a colony, different ants have different jobs, work hours and expertise. However, there aren’t bosses or managers. As Burchill says, “the world’s most industrious businesses are run like hippie drum circles.” If you’re studying social insects, you want to know how it all works. Are some ants lazier than others? How often do workers switch roles? To answer questions like those, you need to be able to tell individual workers apart. That applies to any biologist studying collective animal behavior, such as wolf packs or flocks of geese.

A fan of engineering, Burchill suspected that field could help solve his problem. He turned for help to his adviser, engineer Ted Pavlic of the School of Computing, Informatics, and Decision Systems Engineering. Pavlic studies behavior and complex systems, among other subjects.

“He realized this is a classic engineering situation,” Burchill said. “There’s whole fields of engineering that have been doing this since before I was alive. He whipped up a simple formula to help with the ant situation. Once I found out about that, I thought it was amazing.”

With Pavlic’s experience in telecommunications, he realized the problem is routine in signal processing engineering.

Error correcting codes have been around for decades. They allow receivers to comprehend messages even if part is lost in transmission. Repetition is a basic form of error correction coding. Even if you miss some of the message the first time you hear it, you can fill in what you hear the second time around.

Enter check digitsThe check digit could be defined as the number that will make all nine digits (i.e., the 8 date digits and the 1 new, added digit) sum to a multiple of ten. Since 0+6+1+1+2+0+2+3 = 15, the check digit must be 5 to bring the new total to 20. When the rebels receive this new code, they can reconstruct the entire message even if any single digit has been lost. By adding up the digits in 06/1_/2023-5 (0+6+1+2+0+2+3+5 = 19), a simple check will reveal that missing digit must be 1; otherwise the message would not sum to 20.. Adding a single digit at the end of the message can verify a message or correct it. Vehicle identification numbers, bank account numbers, ISBN numbers in books, bar codes, QR numbers and the codes NASA uses to communicate with the International Space Station and the Martian rovers all use check digits.

But painting numbers on ants is not going to happen. Burchill and Pavlic gave them color-coded “names.”

class="glide image-carousel aligned-carousel slider-start glide--ltr glide--slider glide--swipeable"

id="glide-477850" data-remove-side-background="false"

data-image-auto-size="true" data-has-shadow="true" data-current-index="0">

data-testid="arrows-container">

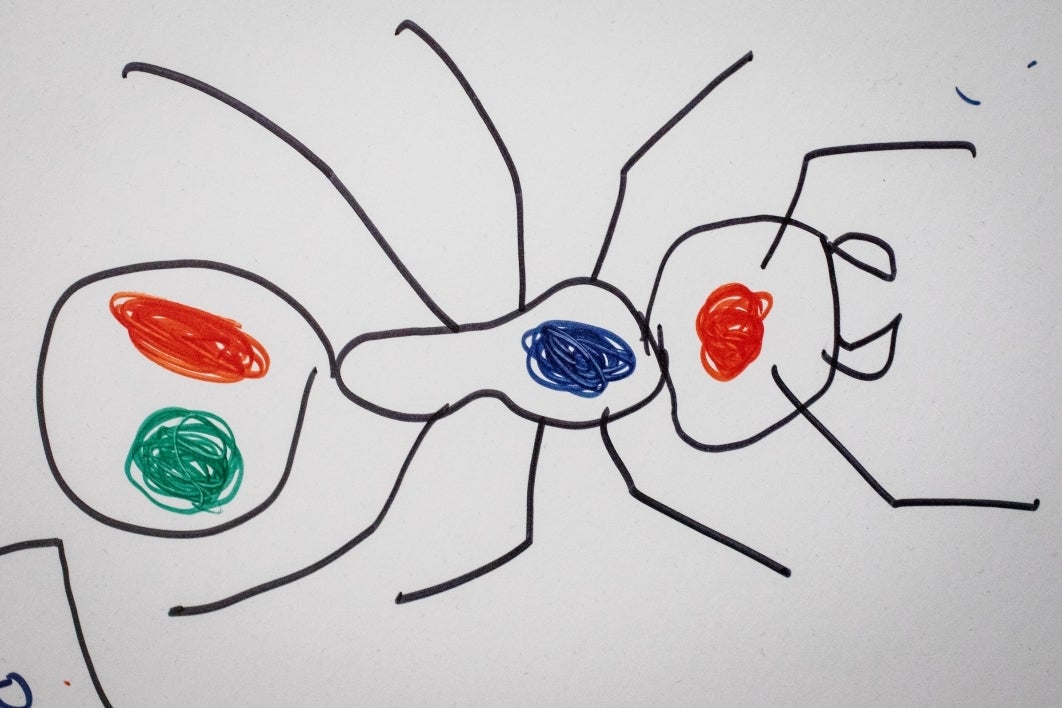

“Red-blue-blue” ant had a red drop on her head and blue dots on her thorax and abdomen. They also added a check drop to the end of the abdomen, to prevent misidentification if any paint is lost or cleaned off. Each paint color is assigned a number. The final dot’s color/number is chosen to bring the sum of the numbers up to a known value. If any paint is missing, they could add up the numbers of the remaining colors and calculate what the missing dot was.

“You can do that to anything,” Burchill said. “If one tag gets lost, you can fix it.”

Burchill’s paper on the method is being published this month in the journal Animal Behavior. He said while it’s not a scientific discovery per se, it’s a solution to a problem that has plagued biologists forever.

“I think that engineering has so much to offer biology, and vice versa,” he said. “If it gets known in myrmecology at all, I would be highly excited. But I would like to give more credit to Ted than me. I see my role as making it more accessible. … Ted’s like God, and I’m more like Moses, so I don’t want to take too much credit.”

He also found another route around his problem.

“I switched to (studying) bigger ants,” he said. “Ones that are easier to paint.”

Top video: Ken Fagan/ASU Now

More Science and technology

Indigenous geneticists build unprecedented research community at ASU

When Krystal Tsosie (Diné) was an undergraduate at Arizona State University, there were no Indigenous faculty she could look to in any science department. In 2022, after getting her PhD in genomics…

Pioneering professor of cultural evolution pens essays for leading academic journals

When Robert Boyd wrote his 1985 book “Culture and the Evolutionary Process,” cultural evolution was not considered a true scientific topic. But over the past half-century, human culture and cultural…

Lucy's lasting legacy: Donald Johanson reflects on the discovery of a lifetime

Fifty years ago, in the dusty hills of Hadar, Ethiopia, a young paleoanthropologist, Donald Johanson, discovered what would become one of the most famous fossil skeletons of our lifetime — the 3.2…