Earlier this summer, almost 100 cars ended up stuck in a muddy Colorado field. An accident in Denver led Google Maps to suggest an alternate route to the airport.

“I took the exit and drove where they told me to,” one woman told a local TV station. The road turned to dirt, then mud. The lead cars got stuck, and the rest had no way of turning around.

None of them apparently paused to think that dirt roads don’t usually lead to major airports. Instead they offered the lemming defense: “Well, all these other cars are in front of me, so it must be OK,” the same woman said.

Blindly following navigation apps has proved to be a losing bet for many people. To wit: A Belgian woman who went to pick up a friend from the train station and ended up in Croatia. The three women in Washington State whose “road” turned out to be a boat launch ramp. The three Japanese tourists in Australia who followed GPS directions to North Stradbroke Island from Brisbane, despite the fact a 9-mile-wide strait separates the two.

How did she not notice she had driven across not just one country, but four or five? That their car was in a lake? An ocean?

It raises the question: Is technology making us stupider?

“Our senses are being overridden by trust in tech,” said Katina Michael, a professor in the School for the Future of Innovation in Society at Arizona State University. “I think we’ve stopped thinking. We don’t want to do the heavy lifting to navigate.”

Michael researches emerging technologies and their social implications.

“Our mind is in the cloud and it has to be on the ground,” she said. “While we have this duality of this virtual and physical space, we tend to allow the virtual to override the physical. That’s what I think is happening. … People have not only lost their ability to navigate, but also their ability to quantify, to assess, to consider even the risks. It’s about us being automated. … We’re getting used to not using our brains in certain ways. That takes away our ability to assess things in general.”

Back to the muddy field outside Denver. What happened there?

“It’s pretty straightforward: Someone trusted their phone nav more than they trusted themselves or their eyes,” said Alex Halavais, an associate professor in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at ASU, where he directs the master's degree program in social technologies.

“I think the numbers there are more an issue of people following the car in front of them rather than the nav in front of the first few people,” he said. “It was a matter of trusting the technology over their experience or their eyes. … It’s not that unusual to trust the navigation works, because you have a background that says it has so far, it hasn’t lied to you yet. In this particular case I suspect it was just a matter of once you made that initial decision it was hard to back out of it — literally.”

What about people driving into bodies of water, a scenario we can all agree lacks ambiguity? Why would they not trust their eyes when confronted with the ocean?

“It’s a matter of 'it works better,'” Halavais said. “My wife makes fun of me when we do the whole Star Wars thing — turning off the targeting computer. When I trust myself over my nav, she makes fun of me. Waze does know better than I do in nine cases out of 10. If you have a track record that says the navigation saves you time or effort over a long period of time, you’re going to keep trusting it.”

Michael zeroes in on the one time out of 10 that tech doesn’t work. She says that’s why we trust it.

“Because it works part of the time, and that’s something I spent a good six years analyzing,” she said. She was awarded a large grant in Australia to look into location-based services.

“What we found is that we cannot always trust tech,” she said. “Tech is not reliable. Tech does not always work. It’s not always accurate. We think because it works most of the time, that it works all of the time, which is why Japanese tourists try to drive from Brisbane to Stradbroke Island, why Swiss tourists go down a goat trail, why someone is driving a car and is going down a boat ramp, even though they can see boats in front of them they keep driving because the GPS says keep driving. What’s going on? It’s the fact we’ve been fooled into believing that the technology always works. … When it fails, it fails cataclysmically.”

So Halavais trusts tech and Michael doesn’t. But their two roads do converge in the wood. Halavais contends some of these cases would have happened anyway — people have been making stupid driving mistakes long before apps appeared — but he argues it’s a nice media hook when it can be blamed on nav failure.

“It’s a microcosm of a much larger issue about trust in technology, which is, I would argue, the most pressing issue of today in terms of our society,” he said. “That seems a little overblown, but it certainly is true. What we trust and how we establish trust has been significantly disrupted by technology, over the last 10 years especially. This is just one small bite of that.”

Don’t trust your instinct and you will lose your instinct, Michael says.

“What’s happened to good old common sense?” Michael said. “A lot of things I talk about in my social implications of technology area is about common sense. I’m not saying anything that’s revolutionary. … What is lacking here is our inability to maintain the use of our brain. When you don’t use something, you lose it. My concern is while we’re allegedly the smartest generation, we’re going to become a dumb generation.”

It’s not a question of "kids these days," Halavais said. It’s a multigenerational issue.

“Technology is people,” he said. “That’s kind of the tricky bit. It’s a very complicated question, how we work out the trust in this. Why do I trust Waze? It’s because I know a little bit about the process by which it’s establishing where the police are. It’s because I know there’s a collaboratory of people out there feeding information into it. I trust that more than I trust Google, where I’m not quite sure how the technology is establishing what it finds. It’s a very complicated set of questions. We also know that those who are older are far more likely to spread fake news, so they trust what they see on Facebook far more than the younger generation does. … Where we place our trust is certainly conditioned by our experience.”

Until now, most people were aware of general rules of travel, like the fact that a 400-mile drive is going to take about eight hours, or that you’re going to get about 300 miles from a tank of gas.

“When our spatial awareness goes, a lot of things suffer,” Michael said. “It’s not just being in a car. It can be being at home. It can be responding to a child. It can be responding to an emergency.”

Our senses are being dulled because automation takes them on without context, she said. We text and write messages like machines. We are becoming automated.

“Kids when they write texts and they put a word on each line — it’s spasmodic, like ‘Get me,’” Michael said. “There’s no structure and there’s no flow to a sentence that says, “Hi Mum, I’ve arrived at the station. How was your day? Can you pick me up?” We’re always trying to do the least number of actions. In being algorithmic like that, context is missing.”

Michael is Australian. Once she attended a dinner and sat next to a brilliant woman, top of her field in the world. The woman asked Michael how long it took to drive from Australia to New Zealand.

“There’s a myopia we’re all suffering,” Michael said. “We work on a little thing but the context of the greater scape of the nation or country or world or our suburb or community is missing. People have lost touch. And because you’ve lost touch with that, everything else is relative. Of course you’re going to be duped by the device, because you don’t even know basic geography. You don’t even know what it’s like to be human, in the world, on the earth. You’re thinking that’s not important, or by some bizarre circumstance you were never taught basic fundamental things. I always say, ‘You might not have to change a tire ever in your life, but it’s good to know how to do it.’”

Top photo by Pixabay

More Science and technology

ASU postdoctoral researcher leads initiative to support graduate student mental health

Olivia Davis had firsthand experience with anxiety and OCD before she entered grad school. Then, during the pandemic and as a result of the growing pressures of the graduate school environment, she…

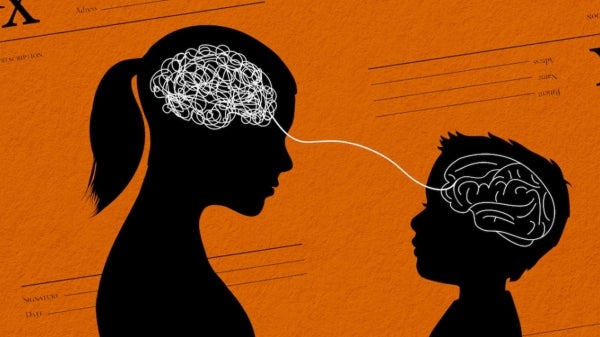

ASU graduate student researching interplay between family dynamics, ADHD

The symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) — which include daydreaming, making careless mistakes or taking risks, having a hard time resisting temptation, difficulty getting…

Will this antibiotic work? ASU scientists develop rapid bacterial tests

Bacteria multiply at an astonishing rate, sometimes doubling in number in under four minutes. Imagine a doctor faced with a patient showing severe signs of infection. As they sift through test…