Standing for hours within crowds of people in hot, sunny and humid conditions is a recipe for heat-related illness — but that’s what spectators at the Tokyo Summer Olympics marathons may be dealing with on Aug. 2 and 9, 2020.

To help city officials and the Tokyo Olympic Committee prepare for extreme heat, Arizona State University senior sustainability scientists Jenni Vanos and Ariane Middel were part of a team that measured and mapped out microclimates along the marathon course to identify hot spots where spectators may face discomfort or illness.

Vanos, Middel and colleagues from the U.S. and the University of Tokyo published a Science of the Total Environment journal article detailing their findings and recommending actions to keep spectators comfortable and minimize their risk of heat illness. Though athletes may be affected physiologically by the heat, the article focused on spectators because they are less likely to train for and acclimate to hot and humid conditions. Tourists, people with pre-existing conditions, children and the elderly are most vulnerable to heat illness.

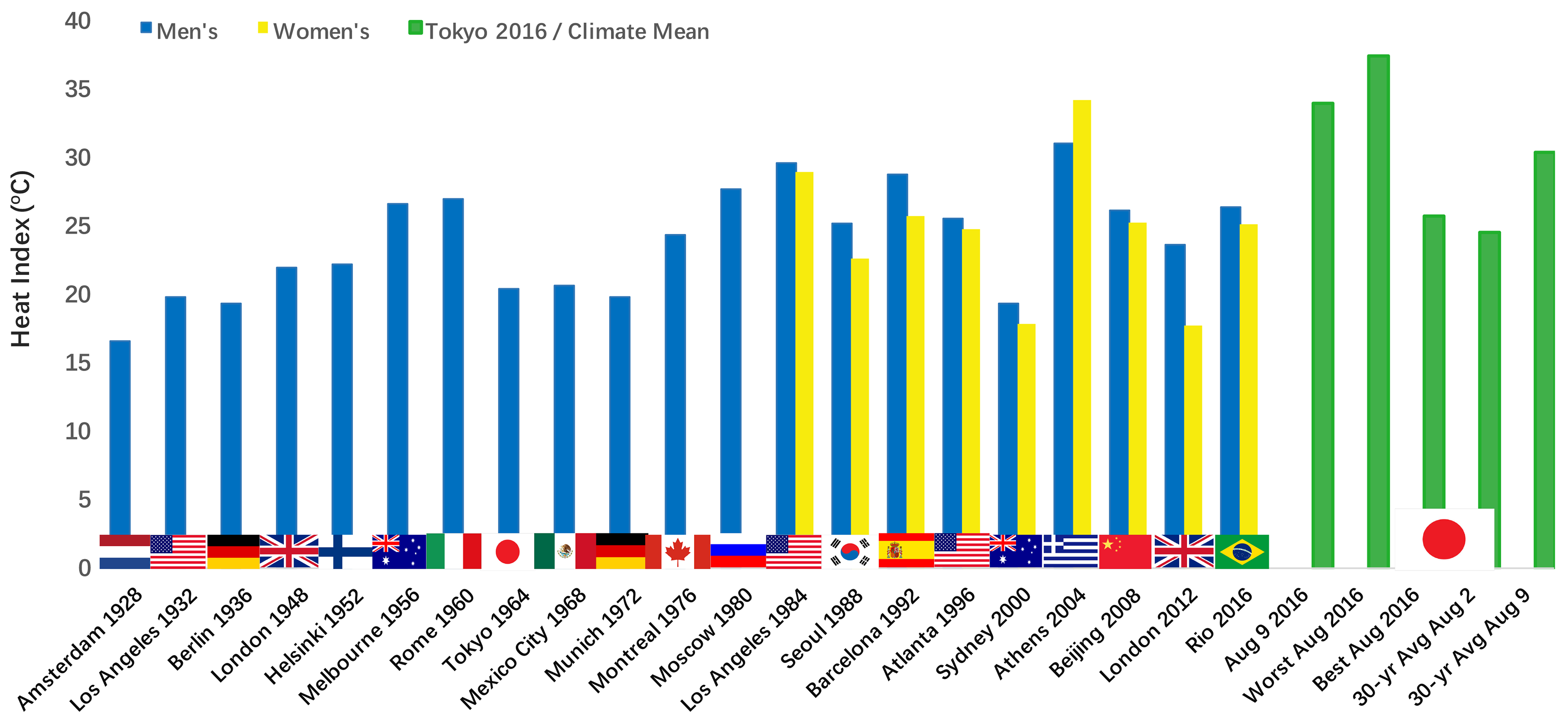

The researchers found that “during the time periods of the marathon races in Tokyo, there is a high likelihood that weather will be the most oppressive of any Olympics — even when held in the morning hours” (see Figure 1 below). In addition, they discovered that thermal comfort varies vastly along the marathon course depending on not only natural conditions such as temperature and windflow, but also urban design factors such as shade, ground cover, and building and tree orientation related to the morning sun.

Figure 1: Heat index during the men's and women's Olympic Marathons 1928–2016 for the given day and time of the event, as compared with expected conditions in Tokyo climatologically or from the current study’s data. Averages are over a 2.5-hour period based on historical information and land-based stations (NCEI, 2017). Graph courtesy of Jenni Vanos

Data-driven strategies

During August 2016 in the morning hours, the team collected 15 microclimate transects along the marathon route using a bicycle-mounted meteorological station and a GPS. These instruments measure air temperature, relative humidity, solar radiation, surface temperature, wind speed, activity velocity, and latitude and longitude. In addition, the researchers used artificial intelligence to automatically determine from Google Street View images if segments along the route were shaded by buildings or trees.

By accounting for all of these factors, the researchers were able to map out thermal comfort along the marathon course and discover where the worst hot spots are. Imperial Palace Square, a popular landmark in Tokyo, is projected to be one of the hottest locations due to the lack of shade from trees or buildings and low windflow for ventilation.

“Shade is the most important factor to keep people cool in hot and dry climates such as Phoenix, but when it’s humid, like in Tokyo, wind plays a more important role,” said Middel, an assistant professor in the School of Arts, Media and Engineering in the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts.

According to Vanos, assistant professor in the School of Sustainability, this is because windflow aids the skin’s evaporative-cooling process, which is the most important process for cooling the body when temperatures are high.

“With the extreme humidity, high temperatures and the immense crowds expected in Tokyo, ensuring windflow via fans and urban design can make a critical difference — essentially allowing more water droplets to evaporate and cool the skin rather than drip off,” Vanos said.

Urban heat-mitigation approaches to protect human health are not one size fits all, Vanos said, which can be understood with an example of misters. Misters succeed in cooling people even without fans in dry environments such as Phoenix, because the dry air allows for evaporation, but fans that increase windflow are absolutely essential in humid environments such as Tokyo. Without adequate windflow to mix the air, misters at the Tokyo marathon would “create an even more oppressive situation for spectators and athletes.”

Smart design along the marathon course in Tokyo would incorporate extra shade and windflow in areas where spectators are expected to be for long periods of time, Vanos said. As recommended in the journal article, other adaptive urban design and coping strategies would include: improving shade and vegetation, providing ventilation, preparing public health officials and emergency responders, and establishing cooling centers.

Many of the article’s recommendations would support sustainable development in Tokyo beyond the Olympics as part of the “Olympic Legacy.” “Although the city of Tokyo may be presented with challenges in coping with extreme heat during the Games, they also have an opportunity to adequately prepare for heat and further leave a legacy to enhance Tokyo's urban sustainability, green space, heat mitigation and residents' health long after the Olympics are finished,” the authors stated.

Times are changing

Since the journal article was released in March, the Tokyo Olympic Committee has decided to change the start time of the marathon from 7:30 a.m. to 6 a.m., an early but positive move. (This early start time is nothing compared with the midnight marathon in Qatar this fall — a time chosen to avoid extreme heat during the Track and Field World Championships.)

Vanos gave insight into why this event is being held in August instead of at a cooler time of year; after all, the 1964 Tokyo Olympics were held in October with more favorable weather conditions.

“Most Summer Olympics over the last three decades have been held in July or August, when the global sports calendar is light and thus when the American broadcasting companies are more willing to pay because they can capture larger audiences,” Vanos said.

More Science and technology

Science meets play: ASU researcher makes developmental science hands-on for families

On a Friday morning at the Edna Vihel Arts Center in Tempe, toddlers dip paint brushes into bright colors, decorating paper fish. Nearby, children chase bubbles and move to music, while…

ASU water polo player defends the goal — and our data

Marie Rudasics is the last line of defense.Six players advance across the pool with a single objective in mind: making sure that yellow hydrogrip ball finds its way into the net. Rudasics, goalkeeper…

Diagnosing data corruption

You are in your doctor’s office for your annual physical and you notice the change. This year, your doctor no longer has your health history in five-inch stack of paperwork fastened together with…