ASU researcher evaluates impact of climate change on avian flu

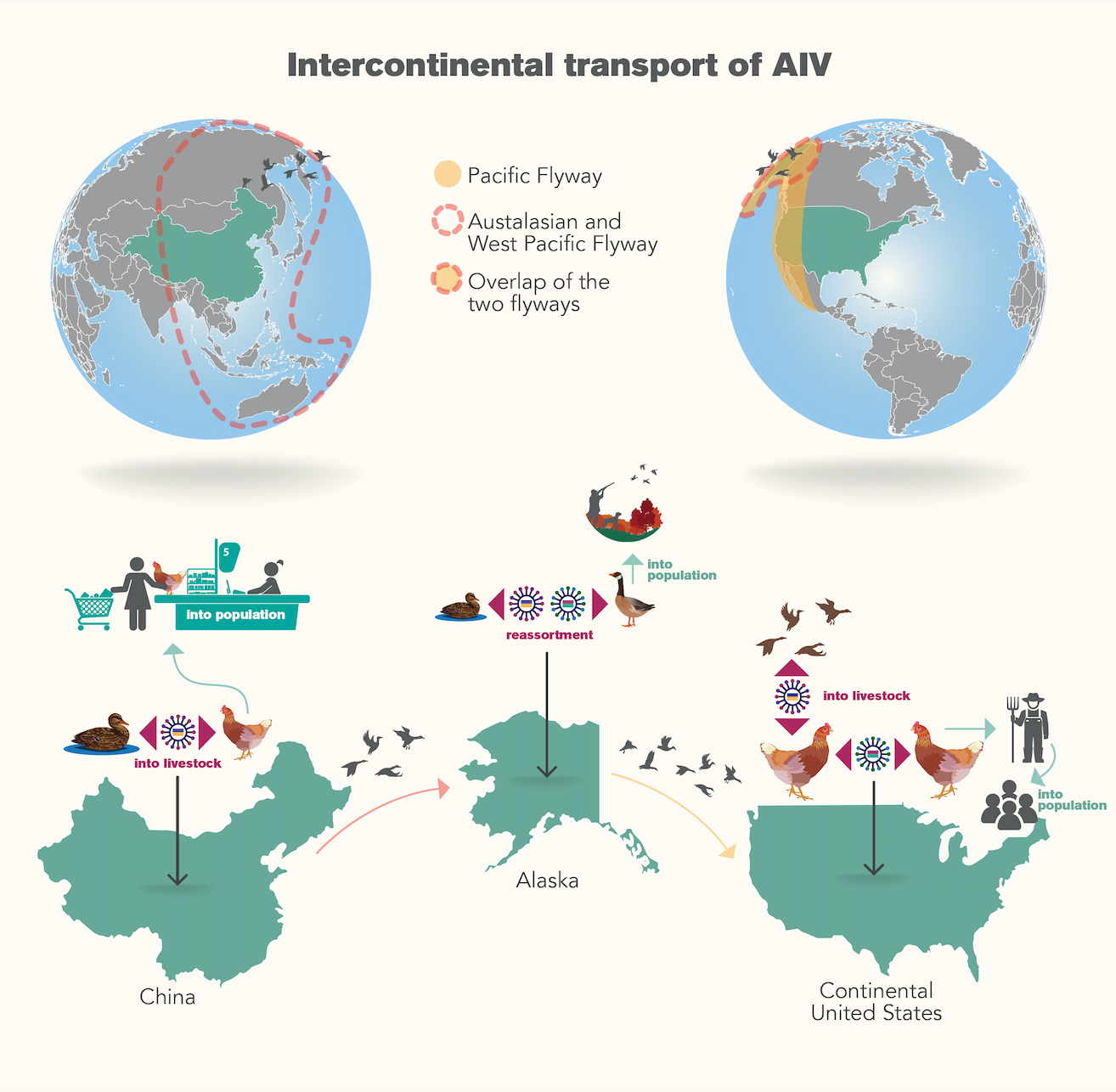

The researchers specifically looked at the impact of climate change on the migration of birds entering the U.S. via the Pacific Flyway from Beringia.

The flu pandemic of 2009 was met by a flurry of panic. This strain of the H1N1 virus, or the “swine flu,” swept across the globe and is believed to be responsible for the deaths of approximately 284,500 people worldwide.

Like a shuffled deck of cards, the virus was the product of the reassortment of avian, swine and human influenza viruses. These ever-changing viral strains pose a formidable challenge to modern health care as they require the development of new vaccines.

One virus of increasing concern to researchers is the avian influenza virus (AIV), as it spreads easily among bird populations and is potentially transmissible to humans. Because bird populations can travel from land mass to land mass with ease, there are higher chances of it reaching a wider range of birds or other species.

The 1918 influenza outbreak, the most severe pandemic in recent history, was caused by an H1N1 virus of avian origin. Its swath of destruction claimed at least 50 million lives worldwide.

There are a plethora of variables that govern the transmission of avian strains of influenza, particularly the migration patterns of the bird species. Climate change has a significant bearing on these patterns — a shift in the global climate could lead to a shift in migratory patterns, leading to the reassortment of these viral strains and increasing the chances of a new, threatening strain emerging. Higher temperatures are also typically more conducive to viral transmission and pathogenicity.

In a review article published for Environment International, Matthew Scotch, faculty member in Arizona State University's Biodesign Center for Environmental Health Engineering and associate professor in the College of Health Solutions, and collaborators at the University of Washington addressed AIV ecology and evolution in the context of climate.

“I have been working with Dr. Peter Rabinowitz at the University of Washington for many years,” Scotch said. “He, like me, has an interest in zoonoses. All of this is impacted by climate change. This includes avian influenza and the introduction of other highly pathogenic viruses that can evolve to cause human-to-human outbreaks.”

Zoonoses are infectious diseases resulting from parasites, bacteria or viruses that can be transmitted among animals or to humans. Upon transmission to humans, outbreaks can occur at a rapid rate. In fact, most human diseases originated in animals — upon mutation, reassortment or the introduction of an intermediate species, humans became their optimal hosts.

In this paper, the researchers first looked at the impact of climate change on the migration of birds traveling via the Pacific Flyway to and from Beringia and then evaluated the resulting changes to AIV ecology.

“There is intercontinental transport of AIV in migratory birds from Asia to Beringia,” Scotch said. “Climate change impacts many things in Beringia and elsewhere including avian migration patterns, overlap of species and viral shedding and reassortment. Then there is intra-continental transport in North America via the Pacific Flyway. You then have local transmission between migratory birds and domestic poultry.”

The paper goes on to discuss all the variables involved in AIV transmission that could be influenced by changes in the climate. For example, AIV persistence will be altered by the changing temperatures of the water the virus inhabits in Arctic areas.

Similarly, the timing of migration to and from the Arctic could lead to increased contact with humans or other bird species, increasing the likelihood of transmission.

However, the paper highlights gaps in knowledge regarding AIV ecology, suggesting that not enough studies have been conducted evaluating changing viral ecology as dictated by changing climatic conditions. To mediate this, the researchers call for the employment of a “One Health” approach, which connects the health of humans, animals and the environment.

“We share this planet with animals — the health of all species is vital. Veterinary and human medicine need to communicate with each other,” Scotch said. “This is especially true for zoonotic diseases like avian influenza. The majority of infectious diseases are zoonotic in origin.”

Although there are other initiatives centered on this theme of the evolution of infectious diseases, the researchers hope to continue promoting climate change’s role in this evolution.

“We are always looking at funding opportunities from federal agencies including NSF and NIH,” Scotch said.

More Science and technology

ASU-led space telescope is ready to fly

The Star Planet Activity Research CubeSat, or SPARCS, a small space telescope that will monitor the flares and sunspot activity…

ASU at the heart of the state's revitalized microelectronics industry

A stronger local economy, more reliable technology, and a future where our computers and devices do the impossible: that’s the…

Breakthrough copper alloy achieves unprecedented high-temperature performance

A team of researchers from Arizona State University, the U.S. Army Research Laboratory, Lehigh University and Louisiana State…