Editor's note: This story is being highlighted in ASU Now's year in review. Read more top stories from 2019.

Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, 1777. At the end of a daylong battle, George Washington’s right flankSomewhere on the battlefield is Private Johan Wilhelm Seckel, 40, the first of his family born in America — and ancestor to ASU Now reporter Scott Seckel — serving with the Germantown Battalion Continental Troops in Capt. George Hubley's Company. has completely collapsed. British troops are closing in.

A dashing Polish cavalry officer reports to Washington’s bodyguard that they are in danger of being surrounded. Washington orders Casimir Pulaski to gather as many men as he can. Count Pulaski discovers an escape route past the British advance, then wheels and charges enemy lines. The redcoats are astounded to be attacked by what they thought was a fleeing rabble. Washington escapes.

Pulaski is revered as the father of American cavalry. He came to America of his own volition to fight in the War of Independence. One of the Revolution’s great heroes, he was a loner. A very private person, he was extremely driven and difficult with people. (It’s one reason Washington simply ended up giving Pulaski his own legion, most of whom were Europeans.) Both superiors and subordinates considered him imperious. He was brave in battle to the point of recklessness. Detractors called him a loose cannon. Short and thin, pacing and speaking quickly, he lacked interest in women or drinking.

And he harbored a secret that lay unknown for more than 200 years, until an Arizona State University bioarchaeologist and a colleague discovered the truth.

Monday night a documentary unveiling the mystery airs on the Smithsonian Channel. But it doesn’t tell the whole story ...

In the late 1990s, Charles Merbs and his wife visited their daughter in Savannah, Georgia. A forensic anthropologist at Arizona State University’s now School of Human Evolution and Social Change, Merbs’ expertise lies in skeletal remains, especially reconstructing behavior from skeletons.

The family toured the historic city, including a visit to Casimir Pulaski’s monument. Merbs is Polish on his mother’s side. His mother always told him they were related to the Pulaskis and should be proud of that. (“It’s been impossible to prove,” he said. “The records just aren’t there.”)

Pulaski was mortally wounded during the Battle of Savannah. (Like most Revolutionary War battles, the American side lost.) He was hit in the groin by grapeshot. Grapeshot was pingpong-size metal balls collected in a canvas bag and fired from a cannon. It acted like shotgun pellets and was used as an antipersonnel round.

He was taken aboard an American ship, where he died a few days later.

“Then the story gets murky as to what happens to his body,” Merbs, now retired, said. “One story is that he was buried at sea on the way back to Charleston. The other story is that in the dead of night his body was taken ashore and buried by torchlight on a plantation. It was done secretly. The plantation owners knew about it and maintained the burial.”

In 1854, it was decided to build a monument to Pulaski. The bones were exhumed and reburied beneath the monument in a metal box.

A week after their visit to Savannah, Merbs’ daughter called. The monument was being taken down. Iron spacers between the stones were rusting. The whole thing was in danger of collapsing.

Merbs tracked down the physical anthropologist working with the bones — Karen Burns, of the University of Georgia — and offered to help. She accepted. “That’s how I got involved,” he said.

Before Merbs was allowed to examine the remains, however, he had to sign a document swearing him to secrecy.

“Basically I couldn’t say anything about what I found until the final report came out,” he said. “Dr. Burns said to me before I went in, ‘Go in and don’t come out screaming.’ She said study it very carefully and thoroughly and then let’s sit down and discuss it. I went in and immediately saw what she was talking about.

“The skeleton is about as female as can be.”

The next — and obvious — question: Was it Pulaski or someone else who had been stuck in the tomb because a skeleton was needed?

Everything seemed to match. The stature, age and general body build were all correct for Pulaski. There’s one contemporary portrait of Pulaski painted from life. There’s a black smudge below his left eye. “On the skull there is a bone defect right exactly there,” Merbs said.

Pulaski injured his right hand in a battle in Russia. “Sure enough; the fourth and fifth metacarpals in the right hand had fractured and had healed rather poorly, exactly where they were supposed to be,” he said.

Merbs has done forensic work with the Maricopa County Medical Examiner’s Office, including working with the skeletons of equestrians. Riding a lot shows up in skeletons. Horse rider’s syndrome is a whole series of issues that affect bones, primarily in the pelvis.

“That skeleton definitely showed signs of horseback riding,” Merbs said, including a new one he added to the lexicon of horse rider’s syndrome: the skeleton’s shoulder showed signs of holding arms high, as would be done holding and pulling back on reins or raising a heavy saber. (Cavalrymen killed enemies by swinging their swords directly down on the crown of their heads. Ever notice the tall bearskin caps worn by the guards at Buckingham Palace? They were designed to protect from exactly that blow.)

The forehead showed an injury consistent with a wound from a blade, although Merbs couldn’t be sure.

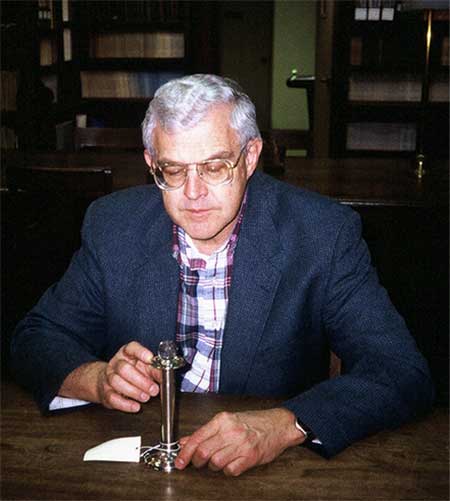

Charles Merbs examines the grapeshot that killed Casimir Pulaski. Photo courtesy of Charles Merbs

“Everything matched, except for the sex,” he said. “The sex was as clearly female as anything could be.”

Something that could be reasonably suspected of a woman in her 30s would be evidence of childbirth. “There were no parturition scars on this pelvis,” Merbs said.

The next step was a positive DNA identification. When the skeleton was exhumed in the 1850s, most of its teeth were missing, except for a few molars.

“Those teeth had been taken out when the skeleton was excavated,” he said.

This was evidence of a macabre but common custom of the time. During the Napoleonic Wars, when millions died in massive clashes, tooth hunters scavenged battlefields. Dead soldiers’ teeth were in great demand for making dentures. (In 1814 an Englishman recorded a meeting with a tooth hunter. When asked how he obtained them, he replied, “Oh sir, only let there be a battle, and there’ll be no want of teeth. I’ll draw them as fast as the men are knocked down.”) After the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, the market became so flooded they became known as Waterloo teeth. Because they came from healthy young men, they were advertised as such.

“It’s very likely around the time the people of Savannah were wearing Pulaski’s teeth,” Merbs said.

They had enough of Pulaski’s DNA to turn the investigation in that direction. But who could they compare it to? Burns and Merbs looked at Pulaski’s genealogy and found out he had two brothers and six sisters. Mitochondrial DNA is passed through women. Of the six sisters, only one had a child. Luckily it was a daughter. She had another daughter. Pulaski and his grandniece would share the same mitochondrial DNA.

Her grave was excavated and samples returned, but nothing usable turned up. “That was 20 years ago,” Merbs said.

Recently three young researchers, one of whom studied archaeology at ASU, decided to look into the mystery. DNA work had come quite a long way in 20 years. Something new might turn up. They got a lab to give them an analysis estimate, which turned out to be $18,000. They contacted the Smithsonian Institute, which funded the research last summer.

The results came back positive. The mitochondrial DNA was identical in both Pulaski and his grandniece.

“Now we know that the bones in the monument were indeed those of Pulaski, but we have the problem of the fact that they are female,” Merbs said. “Here’s the thing: if you go back and look at his life, what we know about it, there are interesting little clues along the way.”

Aristocratic Polish Catholic families in the 18th century traditionally held public baptisms in church.

“In his case it said he was suffering from some debilitatus, and they held off on the baptism and privately baptized him at home,” he said.

Suddenly, Pulaski’s personality traits — aloof, driven, private, brazen in battle — fell into line.

“We think the problem goes back to his birth and basically deciding whether he was a boy or a girl,” Merbs said.

Merbs’ oldest daughter is a professor at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. She put him in touch with a specialist in sex and gender issues.

“With scientists, sex and gender are two totally different things,” Merbs said. “Sex is biological, and gender is social and behavioral. Ordinarily the two go together, but you can have a conflict between the two. That’s what I think we were dealing with here.”

Merbs explained to the professor he thought they were dealing with a sex-gender problem. The professor took out a stack of photographs of bare babies and told him and his wife to put them in one of two piles — girls and boys — which they did.

“One hundred percent,” the professor said. “You are one hundred percent wrong. You were wrong on every single one.”

Merbs thinks the Pulaski family, faced with a similar situation, had to make a decision.

So Pulaski was raised as a man, in a military family. It was without question he would become an officer, and so he did.

“I don’t think, at any time in his life, did he think he was a woman,” Merbs said. “I think he just thought he was a man, and something was wrong. He had some kind of defect or something. Back in those days they just didn’t know.”

Did that perhaps play a part in Pulaski’s aggression on the battlefield?

“Oh, I think that’s a big part of it,” Merbs said. “I think his whole personality indicates he was driven, and I think that’s the reason why.”

Merbs kept his secret, until now.

“This was definitely not what the good folks of Savannah wanted us to find, and the whole thing became a political hot potato,” he said. “They wanted us to verify that the remains were indeed those of a male Pulaski, which would then be interred at Arlington.”

Without conclusive DNA evidence, it was considered that Burns and Merbs' observations were opinion, not fact. The bones were reburied next to the monument.

Burns died several years ago. Merbs has a small credit in the documentary. Both Merbs and Burns names appear in the Pulaski Exhibit in Savannah. Merbs’ contributions are clearly spelled out in an article about to be submitted to the Journal of Forensic Anthropology.

“America’s Hidden Stories: The General Was Female?” will air on the Smithsonian Channel at 8 and 11 p.m. Monday, April 8, and at 1 p.m. Tuesday, April 9.

Top image courtesy of the Library of Congress

More Arts, humanities and education

March Mammal Madness hypes science, storytelling in the classroom and beyond

In classrooms throughout the country, the buzz around March Mammal Madness starts long before the tournament begins. For middle school science teacher Jessica Harris, students wonder which…

Different ways of thinking, different ways of thriving: How ASU is supporting students with autism

According to the CDC, over 5.4 million adults in the U.S. are living with autism spectrum disorder, a condition that affects how individuals interact with others, learn and process information.…

Forever sewn in history

The historical significance of Black influence on fashion spans centuries. From the prints and styles of Africa to various American political climates, Black fashion has sealed its impact on the…